FILM NOTES

FILM NOTES INDEX

NYS WRITERS INSTITUTE

HOME PAGE

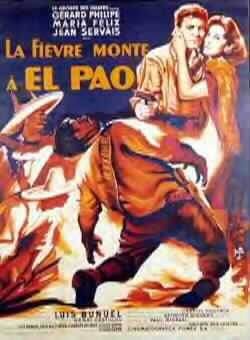

(French/Mexican, 1959, 97minutes, b&w, video)

(In French, dubbed into English)

Directed by Luis Buñuel

Cast:

Gérard Philipe . . . . . . . . . . Rámon Vázquez

María Félix . . . . . . . . . . Inés Rojas

Jean Servais . . . . . . . . . .Alejandro Gual

Miguel Ángel Ferriz . . . . . . . . . . Governor Mariano Vargas

Raúl Dantes . . . . . . . . . .Lieutenant García

Domingo Soler . . . . . . . . . .Professor Juan Cárdena

The

following film notes were prepared for the New York State Writers

Institute by Kevin Jack Hagopian, Senior Lecturer in Media Studies

at Pennsylvania State University:

When the Spanish Civil War ended in 1939, Luis Buñuel was stranded in Los Angeles, struggling to get Hollywood films made which would present the Loyalist cause in Spain fairly. Franco’s triumph made it impossible for the politically progressive Buñuel to return to his beloved Spain, and he would spend the next three decades as a filmmaker without a true home. It was Mexico, with its large but somewhat chaotic film industry, where Buñuel was to find the most hospitable surroundings for his utterly unique, surreal brand of filmmaking. Buñuel would live in Mexico for 36 years, making no less than 20 films there. Several of his finest films were made in Mexico, including El, The Exterminating Angel, and Los Olividados, and Buñuel would look back on his Mexican years not as exile, but as a kind of liberation.

Fever Mounts in El Pao has been unjustly overlooked in discussion of Buñuel’s Mexican period. Perhaps this is merely because of the extraordinary quality of his entire body of Mexican-made films, but a more intriguing explanation is that Buñuel himself disliked recollecting the film. The director was normally loquacious and charming with his interviewers, so his reticence must have struck them as odd. In fact, remembering the film always depressed the gregarious Buñuel. Gérard Philipe, the mercurial and brilliant French leading man of Fever Mounts in El Pao, died shortly after filming was complete, and Buñuel felt bad that Philipe’s last film was, in his own view, not one of his greatest works. Buñuel and Philipe had each accepted the film out of different senses of obligation; Buñuel was living on a shoestring, and has said that he "took everything that was offered to me, as long as it wasn’t humiliating." Characteristically, Buñuel remembers a conversation with Philipe on the subject in surreal terms: "One day during the filming we dropped our masks. "Why did you agree to make this film?" I asked him. "I don’t know," he said. "And you?" I don’t know either," I told him. Neither of us knew why we were working on the film. Cryptically, Buñuel tells us that Philipe was wrong for the film, and that the way we can tell this is by the way the actor wears his pistol too loosely on his belt…

In fact, there is a great deal that is right about this film, and about Philipe in it. In this story of a South American dictatorship in crisis, Philipe plays "Ramon Vasquez," a man who starts out as an idealistic reformer, and then becomes enmeshed in the machinery of the regime. It is a profound parable of political co option, aptly made in a country where a people's revolution had become ossified, its leaders dedicated to preserving their own power rather than empowering their citizens. Buñuel rejected the idea that made political film, seeing his work instead as concerned with the political choices individual people make, but in Fever Mounts in El Pao, the two strands, the national and the personal are woven together, warp and woof. The film is salted with many unforgettable moments. Buñuel enjoyed the spectacles of sadism, and when Philipe’s character is made to do something as prosaic-sounding as picking up broken glass, the effect is oddly excruciating. Buñuel loved to figuratively tie his audiences up and force them to submit to his will, and Philipe, handsome, even dashing, is a remarkable medium for this suffering. And then there is what many consider the climactic moment of the film. Buñuel used to say that he was a respectful plagiarist, and, in Fever Mounts in El Pao, he grafts the ending of Tosca onto the film, in a scene in which the beautiful María Félix confronts a tyrant with the indisputable fact of her sexuality, and a moment of submission becomes a triumph of dominance. Philipe’s character’s choice at the end of the film is as inevitable as it is tragic.

Fever Mounts in El Pao has, dismayingly, disappeared into Buñuel’s vast and glorious filmography, hastened there by its maker’s melancholy anecdotes of its production. In an age when good films are as scarce as they are now, Buñuel’s filmography is a casket of gold, yielding small treasures once unfairly forgotten, even by the master himself.

— Kevin Hagopian, Penn State University

For additional information, contact the Writers Institute at 518-442-5620 or online at https://www.albany.edu/writers-inst.

Fever Mounts in El Pao

Fever Mounts in El Pao