FILM NOTES

FILM NOTES INDEX

NYS WRITERS INSTITUTE

HOME PAGE

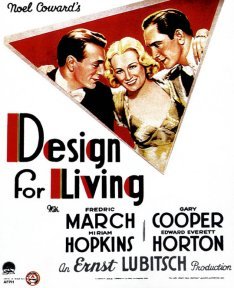

Directed by Ernst Lubitsch

(United States, 1933, 95 minutes, b&w, 35mm)

Starring:

Frederick March……….Tom Chambers

Gary Cooper……….George Curtis

Miriam Hopkins……….Gilda Farrell

Edward Everett Horton……….Max Plunkett

If you had to have a Depression, Paramount Studios was clearly the place to spend it. After the coming of sound, complete by 1929, and before the Production Code elevated prudery to an artistic credo in 1934, some of the sexiest business in the history of the American screen was transacted at Paramount's Bronson Street lot. Mae West held court there, as a voraciously horny Brooklyn dame, in films like She Done Him Wrong and the redundantly titled I'm No Angel; West didn't just tweak the bluestockings, she seemed ready to take after them with a hatchet. Sultry, sexually ambivalent Marlene Dietrich and Josef von Sternberg wove a series of surreal S&M fantasies like Morocco and Shanghai Express at the studio. And in short films and features alike, W.C. Fields leered and double entendre'd his way to immortality as a dumpy, shiftless suburban guzzler who imagined himself a suave roue.

But it was writer-director-producer Ernst Lubitsch who made Paramount the ne plus ultra of sophisticated sexiness. His movies of the early 1930's were like something taken from a scented lingerie drawer. From 1929 to 1934, Lubitsch films promised -- and delivered -- a joyous, unabashedly adult sexuality that movies have tried fruitlessly to recapture ever since. In The Love Parade, Monte Carlo, Trouble in Paradise, The Smiling Lieutenant, One Hour with You, and penultimately, Design for Living, Lubitsch's sexually knowing characters waltzed through their romantic lives without caring a whit for money, armed only with native insouciance and great clothes, and displaying a haughty disinterest in convention. Critics of the day celebrated "the Lubitsch touch," and Design for Living shows just how gossamer that touch was really was; Lubitsch's cosmopolitan air makes a film about a menage a trois seem as regular as a nickel streetcar ride.

The story is as straightforward as it is screwball. Charming gal-of-fortune Gilda (Miriam Hopkins) meets handsome playwright Tom Chambers (Fredric March) and even more handsome artist George Curtis (Gary Cooper) on the train. The three fall in love, and to forestall jealousy, they form a compact that manages to be logical, silly, and romantic, all at once: they will live as a celibate threesome. But this is Lubitsch, and that means that sex will eventually rear its lovely head.

The story is as straightforward as it is screwball. Charming gal-of-fortune Gilda (Miriam Hopkins) meets handsome playwright Tom Chambers (Fredric March) and even more handsome artist George Curtis (Gary Cooper) on the train. The three fall in love, and to forestall jealousy, they form a compact that manages to be logical, silly, and romantic, all at once: they will live as a celibate threesome. But this is Lubitsch, and that means that sex will eventually rear its lovely head.

Noel Coward's already notorious play Design for Living had just closed when Lubitsch set about adapting it. With screenwriter Ben Hecht, Lubitsch junked two-thirds of the play. Coward's windy backstory of the three friends' history together is dumped, and in its place, Lubitsch devises a long, exquisite meeting sequence to open the film. The nearly silent prologue is a filigreed miniature inside an already delicate snow globe of a plot.

Lubitsch's casting was just as daring. On stage, the three lovers had been played by Alfred Lunt, Lynn Fontanne, and Coward himself. Paramount contract player Fredric March, with considerable stage experience behind him and already one of the screen's most versatile players, was a dead-on choice for Tom. His agonized artist-in-a-garret routine, as he beseeches the muse to smack him between the shoulder blades during the writing of the wretched drawing room comedy (or is it a tragedy?) Good Night, Bassington, is one of the highlights of the film. Miriam Hopkins was an actress of famously limited range, but in Gilda, Lubitsch found a part so tailored for her talents that other directors would continue casting her for a decade on the strength of it. When Douglas Fairbanks, Jr., a delightful first choice for George, contracted pneumonia, Lubitsch decided that action hero Gary Cooper would play the role. Everyone, including Cooper, thought Lubitsch mad. Lubitsch, however, had decided to reenvision the play as the tale of a trio of expatriate Americans in Europe, erasing the blase mid-Atlantic sensibility of the original Broadway cast. In Lubitsch's configuration, the midwestern March, the elfin Hopkins, and the lanky Westerner Cooper worked magic, bringing an American exuberance to the straight-laced Continent; where Coward's characters had seemed too exhaustedly cynical to live much past the final act curtain, Lubitsch's musketeers are naively enthusiastic bohemians who make us root for their unconventional behavior. In particular, in Design for Living, Cooper, then at his most unscrupulously handsome, displays reservoirs of loose-jointed comic talent he would not reveal for any another director. Lubitsch liked him so much he would again use Cooper against type in 1938's Bluebeard's Eight Wife.

It is proof of the chemistry of the loony, luminous ensemble created by Lubitsch that the great comic character actors Edward Everett Horton and Franklin Pangborn don't steal the film blind. Instead, they complement the affectionate triad at its center.

What results from the combination of Hecht's "crinkly cellophane aphorisms" (the apt phrase is that of Lubitsch's biographer, Scott Eyman) and Lubitsch's graceful staging and camerawork, is a remarkably contrarian film of the Depression age: a film that airily rejects having money as nice, you know, but rather boring. Like Cole Porter, Lubitsch offered elegance as an end in itself.

After 1934 and the refanged Production Code, the Comstocks and the Bowdlers would try to have their way with the movies, right through the 1950's, forcing Hollywood to keep its feet on the floor whenever it made love. There remained some outposts of adulthood at the studios-- Nick and Nora Charles at MGM, and the films of Howard Hawks -- but Paramount would never be the same. In his post-1934 films, in order to meet the strictures of the Code, Lubitsch had to invent elaborate metaphors for what, before 1934, he, more than any director, liked to state as a simple fact: people love to make love.

For additional information, contact the Writers Institute at 518-442-5620 or online at https://www.albany.edu/writers-inst.

Design for Living

Design for Living