The Endicott

Johnson Corporation:19th Century Origins

Prof. Gerald Zahavi

Department of History, University at Albany

Copyright © 1984, 2010 by Gerald Zahavi

| The following essay is taken from unpublished sections of

my dissertation, with revisions and corrections updating the original 1983 text. As this on-line project progresses, it

will be illustrated with excerpts from newspapers, early company

photographs, selections from the Johnson family correspondence, and donated images from readers.

Please send me your feedback and suggestions for improvements. Gerald Zahavi [zahavi@albany.edu]

Last updated: March 31, 2011 |

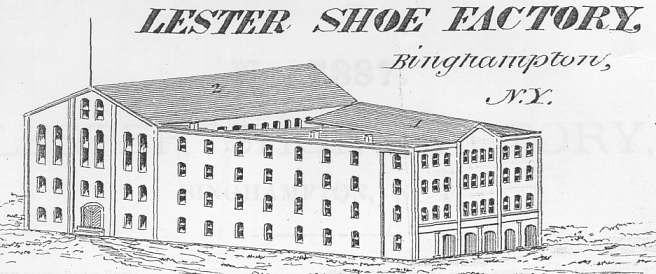

Horace N. Lester—temperance activist, senior officer of the

Binghamton Savings Bank, former mayor of Binghamton, president of the

YMCA, and co-founder of what the local papers exaggeratedly referred

to as the "largest and most successful" shoe manufacturing

concern in the country—died on October 1st, 1882. The large four-story

Lester Brothers factory on the corner of Washington and Henry streets

stood idle for a brief spell, as workers and foremen attended the funeral.

The city's prominent citizens, men who made their fortunes in leather,

cigars, or wood, the three pillars of Binghamton's economy, took some

precious hours and paid tribute to a fellow manufacturing pioneer.[1] Horace N. Lester—temperance activist, senior officer of the

Binghamton Savings Bank, former mayor of Binghamton, president of the

YMCA, and co-founder of what the local papers exaggeratedly referred

to as the "largest and most successful" shoe manufacturing

concern in the country—died on October 1st, 1882. The large four-story

Lester Brothers factory on the corner of Washington and Henry streets

stood idle for a brief spell, as workers and foremen attended the funeral.

The city's prominent citizens, men who made their fortunes in leather,

cigars, or wood, the three pillars of Binghamton's economy, took some

precious hours and paid tribute to a fellow manufacturing pioneer.[1]

Obituaries in local papers praised Lester's active involvement

in Binghamton's social, political, and religious life. But perhaps his

most important contribution to the community lay in the four-story factory

that stood idle on his burial day.[2] From

that factory, and the firm that controlled it, would grow one of the

largest and most integrated shoe manufacturing companies in the world,

the Endicott Johnson Corporation. Horace Lester's death marks a dividing

line, separating one era of shoe manufacturing from another. His entrepreneurial

generation was instrumental in transforming the shoe craft into a shoe industry, replete with factories and all

that accompanies them—machinery, division of labor, bureaucratic shop

management, and class conflict.

This is the story of that transformation, of the workers and managers

of Lester's generation and the world they helped build in the Susquehanna

Valley along the southern tier of New York State.

Leaving behind East Haddam, Connecticut, Horace Lester first

came to Binghamton around 1850 and established a retail shoe trade in

the village. At the time, he was a relatively young man of thirty. He

took on a partner, John Doubleday, and the two of them set up a custom

shoe shop on Court Street, a major commercial block in Binghamton. The

"dingy old store" had a cobbler's bench in the rear, and quite

quickly the bench became the real center of the concern, as retail sales

all but disappeared and Lester took up wholesale or "order" work. Doubleday

soon dropped out of the partnership, for reasons that remain unclear,

but was replaced by Horace Lester's brother, George W. Lester. On September

21, 1854, the two brothers established the firm Lester Bros. & Company.[3] The

Lester brothers were among several New England men, most from Massachusetts,

who ventured out of the safe harbors of eastern seaboard markets and

credit houses and sought their fortunes in shoe manufacturing in the

new urban communities that were growing in upstate New York, Ohio, and

Illinois. By 1880, of the four shoe manufacturing concerns in the city

of Binghamton, three were either headed by or had senior partners who

came from Massachusetts.[4]

It is not surprising to find Massachusetts men at the helm of

Binghamton shoe factories. New England was the national center of shoe

manufacturing throughout the nineteenth-century, with Massachusetts

alone responsible for over 50% of the nation's total shoe production

through most of this period.[5] Hence,

when shoe manufacturing began to spread westward, New England and Massachusetts

shoe men helped carry it.

By the late 1850s and early 1860s, slight market advantages

were starting to make the location of factories in inland regions more

attractive to entrepreneurs. According to one student of the industry,

the westward movement of population widened the distance between New

England producers and westward-migrating consumers. Although this decreased

sales, it was not a sufficiently decisive factor in itself to lead to

the relocation of the shoe trade closer to shifting population centers.

An additional stimulating factor to the migration of the shoe manufacturing

was the growing scarcity of tanned hides along the coast. Tanneries

required hemlock, oak, and chestnut bark supplies, "and as the

bark was used up they moved southward and westward." Thus, the

"interior regions were also beginning to furnish an important part

of the supply of hides."[6]

Complementing these western advantages were a decreasing reliance

on skilled workers, because of the advent of new technology, and a growing

surplus of labor in the West—mainly displaced rural workers. "With

labor and capital becoming relatively cheaper and more abundant in the

West, and with the requirements of previous training becoming less important,

it was only a question of time before the western cities likewise could

develop a localized shoe industry and compete in the national markets."

All these factors helped spread factory production westward, into Rochester,

Cincinnati, Detroit, Chicago, St. Louis, and Milwaukee, and into many

smaller communities along the way.[7]

While many migrating manufacturers made their way to large western

cities, where lucrative local markets could be immediately exploited,

others found their niche in smaller urban centers, such as Binghamton.

Their paths often followed somewhat circuitous routes, as was the case

with one Binghamton shoe manufacturer, James M. Stone. He was born in

New Braintree, Massachusetts, on February 11, 1830. He lived at home,

attended school, and worked on a farm until he was twenty-two years

old. In 1852, lured by stories of gold riches on the West Coast, he

left with a party of other men for the California gold fields. There

he remained for three years and amassed a substantial enough fortune

to return, in 1855, and become a junior partner in a boot and shoe business

in North Brookfield, Massachusetts—in the firm of Gulliver and Stone.

In 1865, the partnership was dissolved, "upon which Mr. Stone came

to Binghamton and established the industry."[8] Whether motivated specifically

by the opportunities of a westwardly shifting market, personal commercial

failures, or merely restlessness, young capitalists like Stone and the

Lesters helped build the foundations of a factory system in Binghamton.[9]

Until the middle of the nineteenth century, Binghamton could

hardly have been called an industrial community. Nestled in an agricultural

and lumbering region, and spreading along the banks of the Susquehanna

and Chenango rivers at their confluence, it did, nevertheless, establish

itself very early on as Broome County's commercial and trading center.

Numerous saw and gristmills, a few tanneries, an iron factory, a plaster

mill, and a handful of other small industries were founded in the village

in the first half of the century. Yet Binghamton grew only modestly

between 1800 and the 1850. It was not until the completion of rail links

with New York, Scranton, Syracuse, and the Great Lakes, in the 1850s

and 1860s that the village really began to industrialize.[10]

The ready access to new markets brought about by the extension of

railroad trackage, the village's proximity to coal-rich regions in Pennsylvania,

and the stimulation of industrial production triggered by the Civil

War soon led to the expansion of the village's modest economy. Cigar,

furniture, boot and shoe, and clothing manufacturers soon took root

in the community. Growing numbers of merchants, industrialists and workers

entering Binghamton swelled its population and led to the re-chartering

of the village as a city in 1867.

Industrial growth continued to fuel population growth. Between

1860 and 1890, Binghamton's population increased from 8,325 to just

over 35,000.[11] Commercial and population expansion not only represented incremental

increases in Binghamton's industrial base but also reflected substantive

structural changes within industries in Binghamton. Nowhere was this

more pronounced than in the shoe industry.

In the mid-nineteenth century, around the time the Lesters established

their shop, important organizational and technological innovations had

already begun to transform boot and shoe manufacturing. The days of

master workmen and apprentices, as well as custom shops, were waning.

In New England, small shops, the "ten footers," were being

abandoned, as workers streamed into the factories that were cropping up

in the many shoe towns that surrounded Boston. The pattern was repeated

in other communities throughout the Northeast. Although the past order

would be sustained both within and without factories, as traditional

craft practices were stubbornly maintained and protected by older workers,

and as small manufacturers continued to operate alongside increasingly

larger factory behemoths, the introduction and perfection of various

technological devices, mainly stitching machines, insured that the future

fate of the industry would lie within factories. There, capitalists

would be able to concentrate machinery and workers and compete handily

with custom shops, survivors of a bygone craft era.[12]

Until the 1850s, machines had played an insignificant part in

the manufacture of boots and shoes. With relatively few hand tools,

skilled shoemakers were able to provide sufficient footwear for both

local and regional markets. But the expansion of wholesale markets just

prior to and during the Civil War placed a premium on rapid and large-scale

production. The introduction and development of several important inventions

during this period—devices such as the automatic pegging machine (1818),

the sole cutting machine (1844), and the leather rolling machine (1846)—did

much to satisfy the imperatives of growing demand, but their impact

on the trade was limited. While they facilitated the standardization

of shoe sizes and shapes, they did not affect key manufacturing processes

such as binding, bottoming, upper leather cutting, and lasting.[13] It was only with the adaptation of Elias Howe's

sewing machine to the stitching of leather uppers, in the 1850s, that

mechanization of the industry really began.

John Brooke Nichols' version of the Howe machine had an immediate

impact on the trade. It quickly put an end to the putting-out system

that had prevailed for three-quarters of a century. Prior to the introduction

of the stitching machine, women bound the uppers of

shoes by hand, working in their homes on materials provided them by

a shoe manufacturer. With the advent of the stitching machine, "binding

and stitching had ceased to be a by-employment which women could carry

on in as leisurely a fashion as they wished," instead, they were

"suddenly obliged to go to a factory and work regularly during

a long working day."[14] The new device also reduced the number of women needed to bind leather

uppers. Between 1850 and 1860, the decade during which the stitcher

was introduced, the percentage of women in the shoe trade dropped from

31_% to 23_% 01880 (from 32,949 to 28,515.[15]

Mechanization of the industry spread with the invention and

perfection of the McKay stitching machine in the early 1860s. Designed

for binding uppers and soles, a task which had been done by skilled

men, the McKay machine was quickly and widely adopted by shoe manufacturers.

The induction of many shoemakers into the Northern armies during the

Civil War and the resulting shortage of skilled labor, compounded by

an influx of large government orders for military footwear, helped promote

the rapid spread of the machine.[16]

David N. Johnson, a skilled Lynn shoemaker who witnessed the

introduction of the McKay stitcher, claimed that the device was capable

of completing as many as eighty pairs of shoes in the time it took a

skilled hand worker to produce just one.[17]

So profound an impact did the invention have on the shoe industry

that it led one observer to declare that the machine "has built

great factories and made thriving cities.[18] The McKay and upper leather stitching machines introduced into

the shoe industry what Alan Dawley has called a "revolutionary

dynamic. . . . As speed and efficiency increased in one branch of production,

other branches strained to catch up, and to restore equilibrium it was

necessary for the whole industry to move at a much faster pace. In this

fashion the introduction of the first sewing machines for binding created

an imbalance in the rhythm of production. Once, it had been necessary

to hire more binders than bottomers to keep the latter supplied with

materials. Now the reverse was true; while binding was done in great

speed with fewer and fewer binders, bottoming lagged behind. Balance

was restored by the McKay stitcher, which vastly increased the velocity

of bottoming, but this change, in turn, created new imbalances vis-a-vis

cutting, lasting, shaping, trimming, nailing, and buffing. . . . In

this period of rapid technological advance, one increase in productivity

beckoned forth another . . . innovation sparked further innovation...change

begat change.”[19]

Indeed, technical innovation transformed the industry in the

second half of the 19th century. The Goodyear welt stitcher,

using a curved needle to sew welt, upper, and insole together without

producing a row of stitches inside the shoe, was perfected in the late

1860s and early 1870s. Employed in the manufacture of finer and more

flexible shoes than the McKay stitcher was capable of, it eliminated

some of the last vestiges of custom work. Edge and heel trimming machines

were introduced in the late 1870s, and in the 1880s, the Metzeliger

lasting machine was invented, taking on the task that lasters had long

boasted could not be done, the mechanical lasting of shoes.[20] Numerous less important inventions accompanied these, all of which contributed

to the erosion of craft skills and to the growing division of labor

that came to characterize the factory.[21]

While mechanization of production generated a dynamic of expansion,

it did not act alone in the transformation of the shoe industry. Rather,

it operated as a catalyst within a complex web of market and managerial

forces that functioned together to create a factory system. As one scholar

has argued, centralization of shoe production inside of factories arose

mainly "because industrial organization, in order to secure uniformity

of output, economy of time, labor and stock, demanded foremen to superintend,

and regular hours of steady work on the part of the men and women employed

in all processes of shoemaking."[22]Yet,

in spite of the technological dynamic that new machines created and

the imperatives of industrial organization, centralization of production

did not occur overnight. What stands out in the evolution of the shoe

industry between 1850 and 1890, is the uneven, often chaotic, mix of

old and new, of custom and innovation. While some shops hastily adopted

new technology, others continued to rely heavily on hand labor. Though

a number of manufacturers built large factories and quickly centralized

production, many did not, and persisted in farming out various tasks

to subcontractors. The decisions made by manufacturers were based on

many factors: their conservatism, the resistance of their workers, the

cost of innovation, the size of the enterprise, the specialization of

the shop. In Binghamton, and particularly in the Lester shop, the growth

of a centralized factory system occurred slowly and at an uneven pace.

The Lester factory began as a custom shop, in 1854, with only

a handful of employees. A year later, it was employing some two dozen

workers, making it the largest manufacturing firm in Binghamton.[23]Through the 1850s and

1860s, the firm continued to expand to meet increasing demand, moving

from one location to another as available working space proved insufficient.

Almost all of the work was done by hand, with only a few foot-powered

devices, mainly stitching machines, in the shop. In 1860, the firm employed 55 workers, 45

men and 10 women. It was manufacturing one hundred dozen pairs of boots

and shoes a week. The growing

market for heavy boots created by the Civil War led to to a rapid increase

in both output and workforce, and shifted emphasis to the manufacture

of boots, at the expense of shoes. By 1865, the firm had moved to a

new building. Production was tripled and additional machinery, mainly

upper leather stitching machines, was purchased. The proportion of women

in the firm's workforce declined, due to both the increasing number

of stitching machines and the emphasis on boot manufacturing, which

involved heavier stitching work—considered men's work. Not until the

late 1880s would their representation in the factory labor force appreciably

increase. But, while the number and proportion of women in the shop

decreased, the overall size of the workforce rose. In 1865, the firm

employed around 120 workers. The anticipation of further expansion soon

led to plans for the construction of a new factory.

Even as the workforce grew and output was increased, centralization

of production came slowly. Following a pattern that was widespread at

the time, shoe manufacturing in Binghamton in the middle of the century

was distributed among various shops and sub-contractors. In the late

1860s, the Lester factory concentrated on manufacturing the uppers of

boots and the bottom stock and shipped both to a nearby contracting shop which specialized in lasting and finishing. This practice was

probably an outgrowth of earlier divisions of labor organized around

"teams" or "gangs." According to one student of the industry, a team

consisted of a number of workers, "each performing a particular process,

the whole team producing an entire shoe. On the other hand, a team might

consist of a group of men all experts upon a single process. Such a

team was known usually as a 'gang.' A gang of bottomers, for instance,

often went from factory to factory, or from employer to employer, having

a contract with each to bottom all the shoes in process of making."[26]

Taking charge and supervising a "team" or "gang,"

the contractor would make contact and obtain contracts with manufacturers.

He generally received a certain percentage of the negotiated contract

price, which varied with the wages he paid his workers. There were all

sorts of variations in the way the system worked, but the pattern was

the same. In spite of all the forces at work consolidating and centralizing

production in factories, the contracting system continued to exist through

the latter decades of the century, sustained by custom. Certainly, sufficient

economic and social incentives existed for its elimination and for the

establishment of direct management of workers by manufacturers through

the use of foremen.

But custom was strong enough to weather the many conflicts and

inefficiencies that accompanied the contracting system. Though

the practice of contracting existed, in one form or another, for over

three-quarters of a century, competitive market conditions exacerbated

its more exploitative aspects in the decades between 1860 and 1890.

Competitive bidding between contractors for jobs often led to increasing

exploitation of employees, as bosses tried to compensate for low bids

by reducing wages of workers or by replacing skilled ex-artisans by

less experienced operatives or "green hands." Such practices

met considerable worker resistance.

"The time is coming," wrote a Binghamton shoemaker in 1869,

"when laborers will command that respect of which contractors and

greedy capitalists have so long robbed them¾and Crispins claim that labor

is their capital, and they, as men, will use it to the best of their

advantage to gain for themselves respectable positions in society to

which they, as American citizens, are entitled.”[27] The statement was written in the wake of a

strike, led by the local Binghamton lodge of the Knights of St. Crispin,

against the Lester shop. The strike itself was not a major event in

either Binghamton history or the history of the Lester shop, but it

does provide us with an indirect opportunity to examine in some detail

the sort of transformations that the Binghamton shoe industry was undergoing

and it does offer us some insight into the impact of these transformations

on the generation of shoemakers who were experiencing the coming of

the factory system.

According to an early student of the Knights of St. Crispin,

Don D. Lescohier, the underlying causes of the Binghamton strike were

the same as those which had brought about the formation of the Knights

of St. Crispin in the first place: the growing encroachments of machinery

and unskilled labor on the status, position, and autonomy of skilled

shoeworkers. Noting the provision in the Crispin constitution which

sought to limit the entry of "green hands" into the trade,

Lescohier identified the Binghamton strike as a typical case of an attempt

to enforce this provision.[28] The introduction of new technology

and the evolving division of labor in factories allowed manufacturers

to segment jobs and to substitute relatively unskilled operatives for

skilled workers, and in the process, to reduce wages. The spread of

such practices finally led to collective action by shoeworkers:

The shoe industry at the end of the war was evidently in a most

chaotic condition. Hand and machine labor was competing fiercely for

the market; and an oversupply of labor was seeking employment. Markets

were lessened though factories had become larger and more numerous.

Unskilled labor was on the machines. Wages were uncertain and falling,

employment irregular and uncertain. Large manufacturers were reducing

wages to increase their competitive advantage, small manufacturers to

save themselves from bankruptcy. Out of this chaos came the Knights

of St. Crispin, the protest of fifty thousand shoemakers against their

unfortunate situation.[29]

The spread of the Knights was nothing less than lightning-like,

reaching almost every major shoe manufacturing community in the nation,

and a number of not-so-major centers. When and how the Crispins first

organized in Binghamton is uncertain. Also uncertain is the extent of

their organization in the late 1860s. Whatever the particular origin

of the local Crispin order, in 1869 it was present and active in Binghamton

and about to take on the community's largest shoe manufacturer. In the

second week of August of 1869, six lasters approached their shop bosses,

contractors for the Lesters, and demanded an increase in their wages. They claimed that other lasters in the city were receiving far

more than they were and that Buckman and Benson, the two contractors,

were exploiting them. The contractors refused the men's demand and the

six of them quit. An officer of the local Crispin lodge, when questioned by a Binghamton reporter,

declared that only four lasters left their work and that they left because

of their "dislike to working with men whom shoeworkers denominate

'scabs'!"[30] Whether the lasters quit because of wages or because of working

with "scabs," it is clear that their action did not provoke

a general strike. The local Crispin organization did not call out the

rest of the men in the shop, because, as one Crispin put it, "our

constitution and by-laws will show that we do not favor or uphold strikes.”[31] In fact, Crispins had no inhibitions about

using strikes to better their condition. The remark was probably made

to gain public support.

The Crispin officer, cited above, was careful to note that the

laster's behavior was "not 'sustained' by the Order, although their

action in this particular is endorsed.”[32]

While the laster's unsatisfied demands from the contractors

had not led to a strike, what did finally provoke a strike was the subsequent

actions of Buckman and Benson: "Buckman and Benson have set at work

ten or twelve green hands in the place of the men who quit work. This

is entirely Crispin principles. The men throughout the shop feel aggrieved,

not only because it is detrimental to the Crispin order, but because

it is hurtful to the shoe making trade thoughout the country, as it

floods the market with poor work, and throws good workmen out of employment.

. . . Now if Lester Brothers' would pay the men the price they pay these

contractors, and deduct from that price sufficient to pay a foreman

to take charge of the work, it would no doubt satisfy the men . . ."[33]

Clearly, the introduction of "green hands"reflected

an attempt on the part of the contractors to reduce costs and maximize

profits at the expense of skilled workers. The Crispins, apparently

blind to the general forces that were increasingly converting former

artisans to factory operatives, merely appealed to the Lesters to rid

themselves of Buckman and Benson and to replace them with a foreman,

thereby eliminating two middle-men. The firm would save money and would

be able to increase the wages of the lasters.

The fundamental issue underlying the conflict in the Lester

shop in 1869 was control, whether voiced as a conflict over wages, "green

hands" or exploitative contractors. That was clear to both George and Horace Lester when they announced to

the local papers that they "claim simply the right to run their

shop in their own way.”[34]

Control, in the context of industrial capitalism, meant regulation

of space, time, technology, wages, and the rituals of work, all of which

were coming to rest in the hands of manufacturers like the Lesters.

It is ironic that while the Crispins were reacting against one particularly

oppressive aspect of an evolving factory system, they were suggesting

a solution which would come to represent merely another phase of regimentation,

centralization, and loss of control over skill. But at this early stage

of factory building, the potential abuses of foremanship were dwarfed

by the immediate experience of an exploitative contracting system. The

Lester factory strike was by no means an isolated event in the late

1860s and 1870s, nor was its underlying cause unique. A number of New

York Crispin strikes dealt with issues related to contracting, particularly

in 1870. In Rochester, for example, six hundred members of the local

Crispin lodge successfully struck and did away with the contracting

system in that city.[35] Although the constitution of the International

Grand Lodge did not contain an explicit prohibition of the practice,

by 1870 the New York lodge added a provision to its by-laws which forbade

Crispins from making "any percentage on the labor of another."[36]

With some exceptions, the Crispins were generally unsuccessful

in overthrowing the contracting system and in halting the replacement

of skilled Crispins by "green hands." In Binghamton, unskilled

workers (and later immigrants) continued to make their way into the

city's factories and it would be another decade before Lester factory

contractors would be replaced by foremen. The Binghamton Crispins were

not destined to see it through. The International Order of the Knights

of St. Crispin declined just as rapidly as it grew, disappearing almost

entirely by1873, a year that marked the beginning of a major national

depression.[37] Along with the International Order went the

Binghamton local.[38] The issue of "green hands" continued to figure in both local

and national disputes as skilled workers persisted in their efforts

to halt the erosion of their skills and status by limiting access to

jobs and machinery. The solution to the exploitative practice of subcontracting

offered by the Binghamton Crispins, namely, the substitution of foremen

for contractors, was widely adopted in due time as the imperatives of

centralization and factory rationalization became more pronounced under

the pressure of expanding markets and competition. But its adoption

came slowly and unevenly, and contracting continued to survive within

factories. As late as the 1880s, subcontractors were still operating

in such places as Philadelphia and Albany. As one student of shoe industry

unionism noted, “[In Philadelphia it] had been customary for the manufacturer

to pay the contractor, who also acted as a foreman, a specified amount

for getting out a certain number of pairs of shoes. In order to get

work the workmen were obliged to tip the contractor. The best and most

steady work went to the one who gave the highest tips. Contractors often

made as much as $300 a week in this way.[39] Only with the rise of the Knights

of Labor in the 1880s did Philadelphia contractors confront an opponent

powerful enough to overthrow them. In other cities, meanwhile, they

were able to weather the challenges of labor organizations. In Albany,

foremen-contractors were still operating in the late 1880s, receiving

a cut of their workers' wages. Vestiges of the

contracting system persisted in many factories through the 1890s, with

foremen, as contractors before them, receiving wages based on production.

In Binghamton, at least within the Lester factory, the practice seems

to have died out by the early 1880s.

Through the 1870s, the Lester factory slowly took on more and more

work that previously had been contracted out. Some time around 1874,

the Blackmer shop, the Lesters' major contractor, specializing in finishing

and lasting, was absorbed into the main

factory. By the early 1880s, around the time when Horace

Lester died, the firm of Lester Bros. & Company was producing over

seventy-two thousand pairs of boots a year and employing as many as

120 workers during the peak working season, a fair sized factory when

one considers that the American shoe factory of the time employed about

57 workers. All production was now superintended by foremen, paid in weekly wages,

and carried on entirely within the factory, a large four-story structure

located in the center of Binghamton's commercial district. The

elimination of the firm's subcontractors and the establishment of a

unified locus of production prepared the way for further mechanization

and expansion.

Horace Lester's death in 1882 created a void in the firm's

management which was quickly filled by his son, G. Harry Lester. George W. Lester,

Horace's brother, had recently retired, and his son, Richard W. Lester, soon joined Harry -- but apparently not at the helm of the firm. According to Richard's great granddaughter, Patricia Sweeney, "Richard worked for a subsidiary company, not for the shoe co. as such. My impression is that he had a weak, melancholy character, thus was no match for his cousin G. Harry, & let G. Harry do what he wanted to." Horace Lester's death in 1882 created a void in the firm's

management which was quickly filled by his son, G. Harry Lester. George W. Lester,

Horace's brother, had recently retired, and his son, Richard W. Lester, soon joined Harry -- but apparently not at the helm of the firm. According to Richard's great granddaughter, Patricia Sweeney, "Richard worked for a subsidiary company, not for the shoe co. as such. My impression is that he had a weak, melancholy character, thus was no match for his cousin G. Harry, & let G. Harry do what he wanted to."

G. Harry Lester took control of the firm

at an opportune moment. The company, like many others, was just emerging from the depths

of depression.The hopes for expansion, kindled by the Civil War

economy, had been dashed in the crash of 1873 and in the subsequent

depression. But in 1882, prospects seemed bright. The revival of the

economy brought an increase of orders from national retail outlets,

such as Montgomery Wards. The firm, under the vigorous and aggressive

policies of G. Harry Lester, began a decade of rapid expansion. The

extent of the company's growth during the 1880s can be measured in rising

employment statistics and in the growing presence of new machinery.

Between the mid-1860s and 1880, rarely did the workforce surpass 120

in number. Yet, in the decade of the '80s, it rose from an average of

95 in 1880 to 425 in 1889, more than quadrupling. By 1889, the Lester

shop was one of the largest factories in Binghamton.

The

size of the female labor force, which had been declining in the 1860s

and 1870s, also began to grow, reflecting the increasing demand for

stitchers and low-paid operatives. In 1880, women had made up around

5% of the workforce (5 out of 95). In 1887, one year after New York

State initiated factory inspections, about 15% of the firm's employees

were women (41 out of 281). Their numbers fluctuated during the next

three years and then suddenly took off. In 1890, only four years later,

women made up approximately 26% of the total labor force (125 out of

475). Women generally took over low paying positions as stitching machine

operators, lining makers, heel blackers and graders, and finishing room

workers. The influx of workers, both male and female, coincided with a rapid

mechanization of production, beginning in the early 1880s. The 1880 federal Census of Manufactures listed

only eight sewing machines in the firm's inventory of hardware, and

no pegging or screwing machines--generally used in the manufacture of

heavy boots. A small 6 horsepower steam-powered engine was sufficient to provide power for all

of the firm's mechanical devices. A survey of the factory taken in November

of 1882, however, disclosed a far larger power source, suggesting the

introduction of new machinery as well as the adaptation of foot-powered

devices to steam power.

The recollections of an old shoemaker in 1919 suggest something of

the variety of the new devices that were introduced into the Lester

factory and that were increasingly becoming typical of the shoe industry

in the 1880s: “While yet in the Henry street plant we had

the Copeland lasting machine, a heeling machine, pegging machine, leveling

machine, a foot-power heel breasting and hand-power heel trimming machine.

Power was furnished by a 40 H.P. upright steam boiler, located on next

to the top floor and leather trimmings formed a large portion of the

fuel.[45] With expanding production, a growing inventory of machinery and a rapidly

multiplying workforce, the firm found itself, once again, searching

for more spacious quarters. It found them. But not in Binghamton.

In 1888, Lester decided to build a new factory two miles west of

the city. Most likely, his decision was based on pragmatic considerations

as avoidance of burdensome city taxes and expectations of profiting

from land sales of inflated property--property inflated by the mere

presence of his factory. But perhaps labor considerations also played

a role. The model of a factory town was a familiar one at the time,

though viewed with some skepticism by the general public. The single-industry

boom towns scattered throughout the country, or Pullman's "ideal

community," suggested the possibilities inherent in such schemes.

The former represented repression, exploitation, class war, and tyranny;

the latter, benevolence, enlightened capitalism, class harmony and uplift.

The public perception of Lester's plan illustrate some of the class

anxieties that were characteristic of the local citizenry, particularly

the middle class, in the latter decades of the century. It suggests

that the Pullman model was far more dominant in their imaginations than

the less benign factory town. The reality, however, as with Pullman,

was far less benevolent.

The Binghamton press, in both descriptive reports and promotional

advertisements, praised the civic and moral qualities inherent in Lester's

planned factory community. Here would be a modest population of workers,

living, in a community controlled by a well-respected capitalist, determined

to provide the benefits and guidance of a middle class life to his operatives.

It would be "Real Philanthropy," as one paper headline suggested,

a community where the harsher elements of modern urban and industrial

life would be eliminated.

In laying out such a plan there are many things to be thought

of. In case of women and children, there are no railroads to cross,

no unpleasant parts of the city to pass over . . . . this tract was

bought simply with a view to establish a place where all people or anyone

desiring a good home with all that pertains to it, could have it at

a very low price. No liquor will be sold on the premises, and no lots

sold with that privilege.

A library building will be built with a free library, reading room

and public above, school house, etc. In that no expense will be spared

to make a pleasant home and furnish entertainment for all outside of

business hours....Tea will be made and served at one penny a cup, and

he [Lester] thinks he can furnish milk to all at two cents a quart.

Coal will be shipped direct from the mines, and an effort will be made

to furnish the necessities of life at the lowest possible cost.[46]

Themes of paternalism and security, civility and safety, a disdain

for the worst qualities of urban living and the harsh realities of a market

economy tended to characterize this and other descriptions of Lester's

plans. These themes were continually repeated in the latter part of the

nineteenth century in the writings of social critics and moralists. They

reflected anxieties over the social cost of a rapidly expanding industrial

order, anxieties that led many to formulate visions of alternative industrial

communities, in the form of literary utopias, such as Edward Bellamy's Looking Backward,

or in the form of "ideal" communities, like Pullman's famed

town. But more often than not, in practice, the anxieties over the expansion

of industrialism and the growth of an uncontrollable working class led

to the rise of factory towns--small, grey, lifeless communities, created

and dominated by visions of wealth, power, or distorted fatherhood.[47]

Lester's community, though seemingly striving for high utopian

ideals, in practice came to resemble the typical factory town.In 1888,

Lester had his agent, superintendent Joseph Diment, buy several parcels

of land in the vicinity of his planned community, and he himself acquired

additional acreage. Whether this surreptitious purchase was accomplished

to avoid arousing the suspicions of potential sellers who might inflate

prices, or merely to get around the hostility of the local farmers to

factories is uncertain. Whatever the reason, Lester quickly had the

tract surveyed, parcelled, and laid out as a village. He began construction

of a home for himself, a "spacious residence," and offered

lots for sale to the general public.[48]

Lester arranged a number of well publicized land auctions, most of

which were directed to "investors" rather than to workers.

A typical advertisement for these auctions read as follows: |

TO INVESTORS

Parties having money to invest can find no

better place to do it than Lester-Shire.

Property in the western part

of Binghamton is rapidly increasing in value and houses

of moderate

cost can find ready renters at good rates in Lester-Shire. This is no western boom, but a healthy growth with

everything in the line of

business to back it up.[49]

|

To attract merchants and professionals, and the well-to-do middle

class in general, it was necessary to convince Binghamton's finest citizens that Lester-Shire would not go the way

of many boom towns, with their rough and undisciplined working class.

These fears were addressed in advertisements such as the following:

The employes of Lester and Co.'s boot and shoe factory

are a steady, industrious, intelligent lot of men and women, many of whom

have already erected handsome and comfortable homes near the factory and

whose example has been followed by others, who are now preparing their

plans or breaking grounds for dwellings. Such a class of men and women

are a blessing in any community, and everyone in these parts thoroughly

appreciates the energy and enterprise of Mr. G. Harry Lester, through

whose efforts so many have been afforded employment and the comforts of

tasteful homes.[50]

Lester's land sales were gala events, with music, refreshments, and

a generally festive spirit. "The band would play a lively air and

the sale wagon could be seen moving through the tall grass and brush,

followed with a mixed crowd of men, women and children."[51] The

festivities, with all the pleasure they may have given their audiences,

also functioned to hide a malevolent feature of Lester's speculations. Lester was enterprising indeed. If investors failed to buy his

lots, he found other ways to sell them, ways which soon put the lie to

any idealistic features his schemes might have had.

sm.jpg) |

A view of Lestershire as it might have looked in 1895. Drawing by S. J. Kelley, E.J. Workers' Review Vol 1:8 (Oct., 1918): 47. |

About the first thing that Harry Lester undertook to do, when he

came to Lester-Shire and built the factory and wanted to sell lots, was

to promise work to those who would come and buy lots of his real estate

agent. He then undertook to compel working people to patronize stores

and hire houses which had been built by those people who were induced

to come there, under the promise that they would be protected in that

way.[52]

Indeed, the authoritarian aspects of Lester's community were soon

demonstrated. In September of 1891, a number of men employed by the Lester-Shire

factory were discharged. Local papers reported their number at anywhere

from thirty-five to a hundred and noted that the men asserted that they

were "discharged because they do not own property in Lester-Shire."

The only explanation the firm offered, however, was that business was

slack. Company officers never answered the charge of selective discharge.[53]

Work and community had thus become united under coercive

auspices. Lester's town was going the way of countless other exploited

industrial communities.

Lester's quest for profits and the immense expense of the construction

project forced him to seek additional capital, and

ultimately led to the transformation of what had been a family firm into

a stock company. In March of 1890, local papers announced that Lester-Shire, land

and factory, would be purchased by a syndicate and would be reorganized

as the Lester-Shire Boot and Shoe Company, while Lester and Co. would

retain control of the factory's jobbing trade.[54] On March 31, the new firm was incorporated,

establishing a main office in Lester-Shire and a district office in New

York City. G. Harry Lester became president as well as general supervisor

of the New York office. The secretary and treasurer of the reorganized

firm was W.D. Brewster, who had been connected with Lester's business

for a decade. G.S. Ackley, who had earlier superintended the construction

of the factory, took charge of the real estate interests of the new firm,

which included approximately 170 acres of land in Lester-Shire. With the

promise of new capital, plans were soon made to grade the streets around

the factory and to add on a 300 foot extension, as well as additional

office space. Local papers reported favorably on the progress of the company

and community. As the Democratic

Weekly Leader noted, “The recent incorporation of the company has

given an impetus to the industries of Lester-Shire. The company proposes

to make generous inducements to foreign interests to locate there. With

influential and moneyed men at its head and a paid up capital of $600,000 back of the concern and the knowledge that more can be

easily obtained, it is safe to predict a phenomenal success for the company

and for Lester-Shire.[55]

Lester-Shire indeed attracted its share of "influential and moneyed

men." It had become, in the words of Grover Cleveland's private secretary,

"just what the moneyed people want--a business of character and standing

where they can invest their surplus."[56] Among the new firm's major stockholders were: ex-secretary

of the Navy William Collins Whitney, who hobnobbed with the rich and mighty

and whose sons married into the Vanderbilt and Hay families; Ohio senator

Henry B. Payne, who had extensive connections with the Standard Oil Company

and whose son, Oliver H. Payne, was the treasurer of Standard Oil; and

Daniel Scott Lamont, private secretary and close confidant of Grover Cleveland,

destined to serve as Secretary of War during Cleveland's second Presidential

term. Serving on its Board of Directors was Charles S. Fairchild, ex-secretary

of the Treasury and president of the New York Trust Company.[57]

Soon after its formation, the syndicate devised a scheme to attract

new enterprises to the community, a plan which guaranteed that the corporation

would both profit from and continue to control the economy of Lester-Shire.

The scheme was described to a reporter by Daniel Lamont: “The company

at first requires the assurance that the proposed industry has done an

annual business, for several years, of $25,000, $50,000 or $100,000. If this can be

confirmed by the company's accountants, a stock company is at once formed

and the Lester-Shire company takes $25,000 or $50,000 worth of stock in the new concern, which thus is given

an added capital to develop its business. All the management of this corporation

wants is to be assured that their money is safely invested, an unlimited

capital is at its command.[58] But a

safe investment was not to be had in Lester-Shire. Almost immediately,

the syndicate's fortunes were imperiled.

The Lester Boot and Shoe Company had looked forward to a period of

rapid expansion. Instead, it confronted depression. The depression of

1893 came early to Lester-Shire. The anticipation of continuing rapid

growth, one that the firm had grown accustomed to through the 1880s, was

frustrated. Instead, orders decreased and workers were laid off. The firm’s

labor force had reached an all-time high of around 475 in 1890, now began

to decline. In 1891, the average size of the workforce shrank to 425.

In 1892, it remained at that figure. And in 1893, it dipped to 400.[59] Lester’s growing neglect of the business

also compounded the firm’s poor fortunes. In the fall of 1890 and through

1891, G. Harry Lester became increasingly involved in land speculation.

After his initial, though short-lived, success with Lester-Shire property,

he began to purchase land for a development in Yonkers, New York. But

his shady financial dealings soon precipitated a law suit against him

by one of his partners. Although Lester denied the charges of embezzlement,

a subsequent court decision confirmed his partner's accusations. On February

17, 1893, a judgement was reached against Lester in the amount of $67,525 for embezzlement of funds from the Nepera Land Co. of Yonkers.[60]

By the fall of 1891, the condition of the firm seems to have greatly

worsened. Plans for a re-incorporation of the business were made. In December

of 1891, the local papers announced that the "Lester boot and shoe

factory of Lester-Shire and the Lester & Co. jobbing house of this

city will cease to exist as two separate firms after January 1."[61] The papers explained

that the reorganization was undertaken in order to "strengthen the

financial resources" of the factory. On January 11, 1892,

the Lestershire Manufacturing Company, the new name of the firm, assumed

control of the jobbing trade, real estate, and factory of the two former

firms. Financed by large western shoe manufacturers as well as by several

Boston businessmen, the company was able to temporarily weather very lean

times.[62] Nevertheless, in the summer of 1892, the company again faced

a financial crisis. The business was on the verge of total collapse. In

fact, papers reported that it had failed and that creditors were attempting

to locate Lester in order to retrieve their investments.[63] The factory actually closed

its doors for a few weeks. Only the hasty salvage operation of Henry B.

Endicott of Boston, a major stockholder and head of the Commonwealth Shoe

and Leather Company, was able to save the firm. Once again the firm was

reorganized, with Endicott as treasurer. George F. Johnson, who had been

the firm's assistant superintendent since 1887 and who had recently been

chosen by Lester to replace his unsuccessful general manager, was retained

by Endicott. Endicott's reorganization of 1892-3 created two companies,

the Lestershire Manufacturing Company, which retained its predecessor's

name, and the Lestershire Boot and Shoe Company. The latter corporation

held ownership of the factory buildings and land while the former took

over the manufacturing end of the business.[64]

Lester's place in all of these events and in subsequent developments

is not at all clear. What is certain is that his connection with the business

was soon severed. Throughout this period, both before and after the firm's

reorganization, Endicott had been lending Lester money and buying up his

notes from other creditors, in anticipation of taking over his remaining

interest in the firm.[65] With Lester's monetary stake

in the Lestershire Manufacturing Company declining, Endicott increased

his involvement with the concern, dealing with its financial interests

out of a Boston office, while Johnson took charge of the daily management

of the factory in Lester-Shire. The two men, destined soon to be partners,

thus began three decades of collaboration.

NOTES

[1] H.P.

Smith, ed. History of Broome County (Syracuse, N.Y., 1885), 216,244,255; George

F. Johnson to the Morning Sun,

September 7, 1922, Box 6, George F. Johnson Papers, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University. Johnson recalls

Lester's funeral in this letter.

[2] See, for example, the obituary in the Binghamton Daily Leader, October 2, 1882.

[3] William S. Lawyer, ed. Binghamton: Its Settlement, Growth and Development and the Factors in

Its History, 1800-1900 (Binghamton,N.Y., 1900), 477, 909; Lester-Shire News, April 11, 1891. Another

member of the firm was Henry A. Goff, a young man who had accompanied

Horace Lester from Connecticut and who became the firm's primary salesman

in the 1850s and through the 1870s. In 1877, he left the Lesters and

became a partner in another local shoe firm, Stone, Goff _& Company.

[9] On the establishment of the shoe

industry in Binghamton see Lawyer, Binghamton,

477-478; H.P. Smith, ed., History

of Broome County (Syracuse, N.Y., 1885), 255-256; William Foote

Seward, Ed. Binghamton and Broome County New York: A History,

Vol 2 (New York, 1924), 412; Dennis P. Kelly, "The Contrasting

Industrial Structures of Johnstown, Pa., and Binghamton, N.Y., 1850-1880"

(Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, University of Pittsburgh, 1977),

46-51, and passim.

[11] United States, Bureau of the Census, Eleventh Census of the United States, 1890:Population\&,

I, 283; Eighth Census, Population of the United States in 1860, 329.

[13] David

N. Johnson, Sketches of Lynn or The Changes of Fifty Years (Lynn, Mass., 1880),

18-21. Information on the early technological developments in the

shoe industry can be found in Frederick J. Allen, The

Shoe Industry (New York, 1922) and in Blanche Evans Hazard, The Organization of the Boot and Shoe Industry

in Massachusetts before 1875 (Cambridge, Mass., 1921).

[14] Edith Abbott, Women in Industry: A Study in American Economic History (New York,

1910), 167. "Binding" was the term employed in the nineteenth

century to describe the process of stitching the uppers of shoes.

"Uppers" referred to the portion of the shoe above the sole

and included vamps, quarters, back stays and collars. A short

shoe trade dictionary can be found in Allen, Shoe Industry, 380-396. See also The Shoe and Leather Lexicon published in various editions by the

Boot and Shoe Recorder Publishing Co. (Boston, 1926).

[15] Abbott, Women

in Industry, 166. The proportion continued to decline until the

1880s. The widespread adoption of the stitching machine in Lynn, Massachusetts,

where women had traditionally been heavily represented in the shoe

industry, was an important factor in provoking one of the largest

strikes in the Nation's history, in 1860. On the strike see Alan Dawley, Class and Community: The Industrial Revolution in Lynn (Cambridge,

Mass., 1976), 77-89, and Paul G. Faler, Mechanics

and Manufacturers in the Early Industrial Revolution: Lynn, Massachusetts,

1780-1860 (Albany, New York, 1981), 222-233.

[16] The name of the stitcher and process

("McKay stitching") came from its manufacturer and merchandizer

rather than from its inventor. Lyman R. Blake, a Massachusetts shoemaker,

actually invented the stitcher in 1858. It was further refined by

Robert Mathias and finally marketed by Colonel Gordon McKay. McKay,

rather than sell the machine outright, initiated a leasing arrangement

whereby manufacturers paid on the basis of production, at a per-piece

price. This royalty system was an important factor leading to the

machine's widespread acceptance, as industrialists did not need to

make any initial capital investments and took no financial risk in

utilizing the new device. The practice of machine leasing became widespread

in the shoe industry and continued well into the twentieth century,

making the trade highly competitive. Entrepreneurs, with little capital,

could easily set up shop. Allen, The

Shoe Industry, 45, 60-61; Hazard, Organization

of the Boot and Shoe Industry, 11, 245-6; Hoover, Jr., Location Theory, 163.

[17] Johnson, Sketches of Lynn, 343-344. This may have been an exaggeration, but

not a large one. See United States Department of Labor, Thirteenth Annual Report of the Commissioner of Labor, "Hand

and Machine Labor," Vol. 1 (Washington, D.C., 1899), 119.

[19] Dawley, Class

and Community, 93-94.

[21] Excellent surveys of boot and

shoemaking machinery and techniques can be found in John Bedford Meno's The Art of Boot and Shoemaking: A Practical

Handbook (London, 1887); in George A. Rich, "Manufacture

of Boots and Shoes", Popular

Science Monthly 41(August, 1892), 496-515; and in Allen, Shoe

Industry, Chapter 2. Recent and not-so-recent treatments of the

Lynn Shoe Industry in the nineteenth century deal with the impact

of technology and factories on workers. See, for example, Alan Dawley, Class and Community, Chapter

3; William H. Mulligan, Jr. "Mechanization of Work in the American

Shoe Industry: Lynn, Massachusetts, 1852-1883," Journal of Economic History, 41(March,

1981), 59-63; Johnson, Sketches

of Lynn.

[24] Lester-Shire

News, April 11, 1891;

United States, Census of Manufactures (Manuscript), 1860; E.-J. Workers' Review 1(August, 1919), 53; "Lester Brothers

Shoe Company," Broome County Historical Society library files.

[25] Binghamton

Daily Democrat, September

6, 1869; E.-J. Workers' Review,

1(December, 1919), 16.

[28] Don D. Lescohier, The Knights of St. Crispin, 1864-1874, Bulletin of the University

of Wisconsin, No. 355, (Madison, Wisc., 1910), 29. Lescohier's description

of the Crispins followed closely that of his mentor, John R. Commons.

See John R. Commons, "American Shoemakers, 1648-1895: A Sketch

of Industrial Evolution," Quarterly

Journal of Economics 24 (November, 1909), 39-83. For a somewhat

different view of the importance of the "green hands" issue

for the Knights of St. Crispin, see Dawley, Class and Community, 143-148, and John

P. Hall, "The Knights of St. Crispin in Massachusetts, 1869-1878," Journal of Economic History 18 (June, 1958),

161-175.

[33] Binghamton

Daily Democrat, September

6, 1869. A notice of the strike appeared in the Binghamton Daily Republican, September 3, 1869. The Daily Republican noted that "this time the strike is general

and among the Knights employed there, but only a small portion of

their hands were members of the order."

[36] “Constitution of New York State

Lodge of the Knights of St. Crispin,” Art. XV, 20, cited in Lescohier, Knights of St. Crispin, 48. The International

constitution did contain the following provision, inserted in 1872:

"Your committee censure the system of a Crispin making a profit

on the labor of a Brother Crispin,

as contrary to the spirit of Crispinism, but consider it impracticable

for the I.G.L. [International Grand Lodge] to frame a law governing

the case, we therefore recommend this I.G.L. to instruct subordinant

Lodges to insert an article in their by-laws suitable to their different

localities." Cited in Lescohier, 48.

[37] In the late 1870s, an attempt

was made to revive it. The second Knights of St. Crispin was far smaller

and more conservative than the first, and did not last very long.

It was probably absorbed by the Knights of Labor in the 1880s. See

Lescohier, Knights of St. Crispin, 56-59. The Shoe Workers' Journal 11 (May, 1910),

8-9.

[38] Although it is very difficult to prove (since membership lists are

not available), many Binghamton Crispins, as was the case in Cincinnati,

probably joined the local assembly of the Knights of

Labor. Local Assembly 2186 was active in Binghamton throughout the

1880s and into the early 1890s. In 1883, an independent Assembly was

formed, breaking away from Local Assembly 2186. See Terence V. Powderly, Thirty Years of Labor, 1859 to 1889 (Columbus, Ohio, 1890), 192, 568-573;

Osterud, "Mechanics, Operatives and Laborers," Working Lives, 99. Binghamton papers periodically

made mention of the activities of the local Knights of Labor, particularly

during periods of labor strife.

[39] Augusta E. Galster, The Labor Movement in the Shoe Industry (New York, 1924), 54-55.

[40] New York State, First Annual Report of the Board of Mediation and Arbitration, 1887

(Albany, 1888), 22,28,42,73.

[41] Undated clipping in Frederick

Wallace Putnam Document Collection, Vol. 77, p. 166, Binghamton Public

Library; E-J Workers Review, 1(May, 1919), 24-25.

[44] "Lot Surveys," Box 32,

George F. Johnson Papers; United States Census

of Manufactures (Manuscript), 1880.

[48] Lawyer, Binghamton,

650-651. Binghamton Press,

April 11, 1914.

[49] Binghamton

Daily Republican, January

14, 1890. See also June 3, 1890, June 11, 1890 and August 31, 1891

for more examples.

[50] Binghamton Daily Republican,

June 4, 1890.

[52] E-J

Workers Magazine, 4

(September, 1925), np. This is George F. Johnson's recollection of

Lester's activities.

[55] Democratic

Weekly Leader, April

4, 1890.

[57] W. Lester, an original partner in the Lester Co. and a distinguished

financier in his own right, had apparently been instrumental in bringing

these men together and in arranging the transfer of the firm to a

syndicate. Democratic Weekly Leader, April 11, 1890. Dumas Malone, Ed. Dictionary of American Biography (New York, 1933), XX, 165-166; XIV,

325-326; X, 563-564; VI, 251-252.

[59] From 1894 and well into the early

years of the century, the workforce steadily increased, nearing 2000

at the turn of the century. New York State, Report

of the Factory Inspector, 5th through 15th Annual Reports (Albany,

1891-1901).

[61] Democratic

Weekly Leader, December

25, 1891.

[62] Lestershire

Record, March 26, 1897.

The only surviving copy of this issue available is in the Broome County

Historical Society Library.

[64] George F. Johnson to G. Harry

Lester, March 12, 1928, Box 9, George F. Johnson Papers;

Biographical Review [Binghamton], (Boston, 1894), 91-92; Binghamton Sun, November 29, 1948; Binghamton Republican, March 17, 1897; Binghamton Evening Herald, March 17, 1897.

|

|