Albany Magazine Stories

Published by the University Relations Office, University at Albany

Features: Shelby Foote, Stephen Jay Gould, Joyce Carol Oates, August Wilson

August Wilson: Hearing His Characters All Over Town

August Wilson: Hearing His Characters All Over TownBy Paul Grondahl

August Wilson spoke at the University at Albany on April 8, 1996 as part of the New York State Writers Institute's Visiting Writers Series. The following article by Paul Grondahl appeared in the Fall 1996 issue of Albany, the University's magazine.

Playwright August Wilson--who has won two Pulitzer Prizes, six New York Drama Critics Circle awards, a Tony and most of the other hardware the American theater hands out to honor excellence--has a ritual to prepare himself before beginning his work. He starts by washing his hands. “It’s a symbolic cleaning because I consider writing a mystical and spiritual experience,” Wilson says.

Sometimes, he works at home on an old manual typewriter. But, more often than not, when he’s getting ready to write, he feels restless, edgy, full of pent-up energy. He goes for a walk. He lives in Seattle now, but the routine was the same when he lived in Pittsburgh and St. Paul, Minnesota, and New York. Wilson’s mid-morning meandering ends in a diner, a tavern, a cafe, a coffee shop. Wilson claims a deserted stretch of the bar or a back booth, orders a cup of coffee, pulls a pen and small notebook from a jacket pocket. He takes a few deep breaths. Gets relaxed. Hunches over the blank page. And waits.

“Whoever wants to talk to me, I’m there, open,” says Wilson, meaning not friends or acquaintances, since he remains an anonymous stranger on these writing forays, but the characters in his dramas. “Sometimes, nobody wants to talk to me. That’s cool. I’ll wait awhile and if it’s no good, I’ll move on to the next coffee shop. Like fishing. Eventually, something starts to happen.”

His characters begin to speak to him, a deep soulful sound. Wilson grew up listening to the blues. “The blues are at the bedrock of everything I do,” he says. “I think the blues is the best literature black Americans have. I can’t sing, so I said if I can’t sing the blues, I’ll write them.” Wilson, one of America’s most celebrated playwrights, possessed of an incomparable ear for the bluesy rhythms of African-American dialogue, hears the music of his character’s voices and lets it carry him away.

“Writing for me,” he says, “is like walking down a landscape of the self. You encounter your own demons amid armies of memory.”

Wilson allows this psychic sound, what James Baldwin called “loud action,” to transport him back to his youth, to hardscrabble lives of inner-city Pittsburgh of the 1950s. He listens to the voices of African-Americans speaking about their dreams and ambitions that will allow them to soar above their sorry patch of asphalt ghetto in the city of steel. He begins to put pen to paper.

That writing ritual has produced the finest and most celebrated plays of his generation: “Jitney,” “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom,” “Fences,” “Joe Turner’s Come and Gone,” “The Piano Lesson,” “Two Trains Running” and “Seven Guitars.” Wilson sets each play in a different decade of 20th century America and, taken together, they comprise a body of work of astonishing range and ambition that places him on the top shelf alongside this country’s most acclaimed playwrights. Eugene O’Neill. Tennessee Williams. Arthur Miller. Edward Albee. August Wilson. Wilson’s plays probe African-American history and culture and critics focus on his mastery of black speech, but his work transcends all labels. The themes that range across his plays do not make a distinction between black and white. His characters struggle with love, honor, duty, betrayal, loss and redemption. His plays are full of “compassion, raucous humor and penetrating wisdom,” in the words of New York Times critic Frank Rich.

When the work is going well, writers will tell you, they may experience a rare and fleeting moment of transcendence when they attain that magical flashpoint of consciousness in which time stands still. For Wilson, that feeling of being in the writer’s zone, undisturbed by boundaries of time and space, occurs with unusual regularity.

“I’ll be sitting at a totally empty bar, scribbling away, oblivious to everything,” Wilson says. “I don’t know where the writing is going, but my characters take me away. I start asking questions. I don’t know the answers, but they are revealed as I go along. It’s a spontaneous act of discovery, a journey. The writing just flows and flows and you can’t stop it. Next thing I know, I look up and it’s late-afternoon, I’ve been sitting there for hours, and the bar has filled up around me.”

We are talking over cups of coffee in a restaurant at the Albany Omni Hotel on an April morning, three weeks shy of Wilson’s 51st birthday. His latest play, “Seven Guitars,” is running on Broadway. Wilson is visiting the University at Albany to teach an informal writing seminar and to give a public reading as part of the New York State Writers Institute’s visiting writers series. “August Wilson is our best American playwright,” Donald Faulkner, associate director of the Writers Institute and a Pittsburgher like Wilson, says by way of introduction at the seminar.

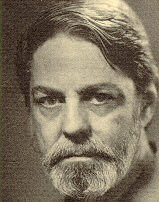

Wilson is tall and powerfully built, with a football lineman’s bulk. His head is bald, a round face ringed with a salt and pepper beard and mustache. His father was white and mother black and his skin is light, the color of cafe au lait. His eyes are the color of chestnuts and they shine when he tells an anecdote in his soft, sibilant voice. He doesn’t mind poking fun at himself and is a generous, thoughtful man in conversation.

A high school dropout who grew up in poverty, Wilson tells of how he educated himself in the back stacks of the Pittsburgh Public Library and, at the age of 19, wrote a college term paper for his sister on Frost and Sandburg. She sent him $20. Wilson took the money and bought his first typewriter, a Royal manual, on April 1, 1965. “It weighed about 35 pounds and I lived at the top of a long hill and that thing felt like 55 pounds when I got to the top,” Wilson says. “All I knew is I wanted to see my name in print.”

He quickly typed up three poems and submitted them to Harper’s magazine. They were returned in the next day’s mail, without the courtesy of even a form rejection letter. Wilson stubbornly continued to write poetry in Pittsburgh, without much success, and moved to St. Paul, in 1979 to take a job as a script writer for educational skits for children at the Minnesota Science Museum.

Wilson was writing serious drama on the side and, in 1982, a draft of “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom” was accepted for a workshop production at the Eugene O’Neill Playwrights Conference in Waterford, Conn., where Wilson was teamed with director Lloyd Richards. Richards and Wilson have worked together ever since, with each of Wilson’s plays premiering at Yale Repertory Theatre under Richards’ direction before moving to Broadway. “August is a wonderful poet,” Richards said in a 1986 New York Times interview, “A wonderful poet turning into a playwright.”

As concessions to middle age, Wilson stopped smoking four years ago, quitting cold turkey a four-pack-a-day habit, and switched to decaf coffee. He says he feels more vital than ever before.

“I’m just entering my prime, ready to do my most mature and serious work in the next 10 years,” Wilson says. “I know I haven’t hit the peak of my powers yet.” With seven plays already in the decade-by-decade cycle, and a new play underway, set in 1984, it is suggested that he’s outpacing the 20th century. Wilson is ready for the literary challenge of a new genre. He’s writing his first novel.

“I’ve been toying with this novel for eight years and I’ve only got 60 pages,” Wilson says. “My problem is I can’t find the voice. But I have some things I can’t do in plays that I think I can get at in a novel. You’ve got so much room to work in a novel. But writing fiction is all new to me. It’s like crossing an ocean without any maps. I don'‘ know where I’m at or how I’m going to get to the other side. Once I truly immerse myself in the novel, I don'‘ anticipate any problems. It’s all about telling a story.”

“Seven Guitars,” set in 1948 in the Hill district of Pittsburgh (where Wilson grew up), has a “novelistic sweep,” said Vincent Canby, in his New York Times review. The play is told in flashback in the backyard of a tenement where friends of Floyd “Schoolboy”, a blues guitarist who has lived the themes of his music, gather for a wake following his funeral.

Barton is a sweet-talking ladies’ man who ends up broke and in jail, when a blues recording he made months before becomes an unexpected hit. Barton’s journey involves finishing his sentence and trying to get back with the woman he loves, to claim the fruits of his musical labor and to play among the blues greats in Chicago. “Here’s a play whose epic proportions and abundant spirit remind us of what the American theater once was (before amplified glitz became dominant), and still is when the muses can be heard through the din,” Canby wrote.

Wilson sounds like a revolutionary when discussing the recent artistic disappointment and increasingly crass commercialism of Broadway. “The costs of mounting a show on Broadway have become astronomical,” Wilson says. “Broadway is just 34 pieces of real estate. One guy owns 19 Broadway theaters, another one seven, and a couple more own the rest. Most of the time these huge, beautiful theaters just sit empty. I say the playwrights should claim the theaters. They’re wasted real estate right now. We should just take them over, because the future of the theater is in the hands of the playwrights.”

Wilson sounds like a revolutionary when discussing the recent artistic disappointment and increasingly crass commercialism of Broadway. “The costs of mounting a show on Broadway have become astronomical,” Wilson says. “Broadway is just 34 pieces of real estate. One guy owns 19 Broadway theaters, another one seven, and a couple more own the rest. Most of the time these huge, beautiful theaters just sit empty. I say the playwrights should claim the theaters. They’re wasted real estate right now. We should just take them over, because the future of the theater is in the hands of the playwrights.”

Wilson can laugh about the setbacks along his playwright’s journey. He recalls the Broadway opening of “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom.” Wilson was a smoker back then and rushed out onto the sidewalk at intermission to have a cigarette. A fellow playgoer lighted up his smoke, muttered an expletive to describe his reaction to Wilson’s play, tossed the playbill into the gutter and stormed off into the Manhattan night. Wilson kept the crumpled-up program. It rests beside his Pulitzers and a shelf of other awards.

Top of Page

Stephen Jay Gould: So Smart, It’s Scary

Stephen Jay Gould: So Smart, It’s ScaryBy Paul Grondahl, M.A.’84

Stephen Jay Gould spoke at the University at Albany on December 5, 1996 as part of the New York State Writers Institute's Visiting Writers Series. The following article by Paul Grondahl appeared in the Spring 1997 issue of Albany, the University's magazine.

The bookish boy who loved dinosaurs, taunted mercilessly by the other kids as “fossil face,” has been savoring his sweet revenge ever since. Fifteen minutes before the scheduled start of his lecture at four o’clock in the afternoon on a wintry December Thursday at the University at Albany, Stephen Jay Gould had filled the main theatre of the Performing Arts Center beyond capacity, with dozens of students sitting shoulder-to-shoulder in the aisles.

There was a palpable buzz of excitement in the air as the crowd awaited Gould. After some squeezing and repositioning to safely accommodate more than 600 fans of the work of the Harvard University evolutionary biologist -- who has discussed complex scientific notions for the attentive reader through the course of 13 acclaimed books and an unbroken 22-year streak of monthly columns in Natural History magazine -- the great Gould was ready to begin.

Almost. Gould has earned a reputation for being difficult and, as one example, he forbade the taking of photographs during his speech. When a camera flash pierced the auditorium, Gould stopped and seethed. Like a temperamental maestro, Gould brooks no interruptions and received no more during an hour-long reading of a previously published Natural History essay on the evolution of horses, accompanied by his own lively commentary that formed a kind of essay-within-an-essay.

In typical Gouldian fashion, his discussion of evolution drew together a constellation of seemingly disparate sources -- from Shakespeare to the television show “Dragnet,” from Darwin to “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” -- that o’erleaped the confines of logic to form their own brilliant connections and universal truths. It’s as if he rummages around in the vast attic of ideas in his mind and alchemizes the dross into gold.

Gould defies classification: paleontologist, geologist, biologist, evolutionary biologist and Renaissance Man all have been used as shorthand modifiers, but each fails to encompass the essential Gould oeuvre. He’s so smart it’s scary.

In collaboration with paleontologist Niles Eldredge, Gould formulated the important evolutionary theory of “punctuated equilibrium,” modifying Darwin in a way that sees non-change as the norm, with nature offering rapid and sweeping permutations in small segments of a species rather than by the slow and steady transformation of entire ancestral populations.

The theory blows holes in the commonly held notion of evolution as a relentlessly upward climb with humans at the top. The extinction of dinosaurs, for instance, occurred in response to an event rather than a slow, drawn-out inevitability, according to Gould. In books such as Flamingo’s Smile, he celebrates the importance of randomness and unpredictability in the history of life.

“We’re not as powerful as we think,” Gould told the University audience, noting humans are an oddly singular and tiny evolutional blip on the radar screen, separated from other mammals only by our consciousness, and badly outnumbered, for instance, by the million or so species of arthropods alone. “We have no right of domain over this planet. We’re latecomers compared to bacteria, which have always been here and are going to beat us for sure. Humans are just one species struggling along and we’d better work together to keep it going.”

Gould’s visit was the last reading in the fall visiting writers series sponsored by the New York State Writers Institute, and after his reading, he was swallowed up just off stage by fans thrusting books at him. “I won’t sign them here,” he said. A high school student whispered to a friend as he was swept along in the pack vying to get close to Gould: “It’s like he’s the president or something.”

He didn’t look presidential. Gould looked beleaguered, clutching the same large, heavy black briefcases bulging with books -- one in each arm, as if to achieve a kind of equilibrium -- that he lugged along during a visit to the University in 1991 for the Writers Institute’s “Telling The Truth” conference. It’s good to see age (he’s 55 now) hasn’t softened Gould; he wouldn’t grant interviews then and he won’t grant interviews now. Gould remains in all things his same uncompromising self.

To be fair, Gould was loose and generous -- even jocular -- when meeting privately with a small group of students from a biology class at Guilderland High School prior to his public reading. He lounged on a stage, his stout body sprawled childlike across the floor, dressed in rumpled chinos, brown penny loafers, blue dress shirt and brown tie with a diamond pattern. He smiled, laughed and brushed back his thick helmet of silvery hair as he told the students about how he would ride the subway with his father from their home in Queens to the American Museum of Natural History on Manhattan’s Upper West Side beginning at age five.

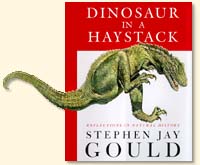

The young Gould was mesmerized particularly by the skeleton of Tyrannosaurus rex, gripped by a mixture of awe and fear. In adulthood, he would revisit such formative experiences in, among other books, Dinosaur in a Haystack and Bully For Brontosaurus. “I guess I sort of fulfilled what I was meant to do since age five,” Gould told the high school students.

The young Gould was mesmerized particularly by the skeleton of Tyrannosaurus rex, gripped by a mixture of awe and fear. In adulthood, he would revisit such formative experiences in, among other books, Dinosaur in a Haystack and Bully For Brontosaurus. “I guess I sort of fulfilled what I was meant to do since age five,” Gould told the high school students.From a passion for dinosaurs, he graduated to collecting shells at age eight at Rockaway Beach, and then to hunting for fossils as a teenager. After majoring in geology and earning a bachelor’s degree at Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio, Gould earned a doctorate from Columbia University in 1967 for work in geology and invertebrate paleontology. He’s been teaching at Harvard University since 1967 and holds the position of curator of invertebrate paleontology for Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology.

In his personal life, he’s endured his share of painful random events. Gould is the father of an autistic son. His marriage of 30 years broke up (he has since remarried). He was diagnosed in 1982 with a deadly asbestos-linked cancer, abdominal mesothelioma, with a median mortality of eight months. After surgery and chemotherapy treatment, Gould is in remission. He once described himself as “a tough cuss.” As a writer, he’s that rare species, author of books on paleontology and the history of science that are best-sellers and highly regarded among scholars.

He’s done for fossils and dinosaurs what Carl Sagan has done for the stars. In doing so, Gould has won the National Book Award, the National Book Critics Circle Award, the Phi Beta Kappa Science Award and was among the first recipients of the MacArthur Foundation’s so-called “genius” grant.

“I write these essays primarily to aid my own quest to learn and understand as much as possible about nature in the short time allotted,” he wrote in the introduction to The Flamingo’s Smile, his 1985 collection. “Every month is a new adventure -- in learning and expression.”

Gould is eminently quotable, but two notions from his 1993 book, Eight Little Piggies: Reflections In Natural History, offer a window onto Gould’s accomplishments. “Extinction is the ultimate fate of all and prolonged persistence is the only meaningful measure of success,” he wrote. Also, “Details are all that matters: God dwells there, and you never get to see Him if you don’t struggle to get them right.”

“I’m a total autodidact as a writer,” Gould confessed to the University audience. The essay Gould read, “Mr. Sofya’s Pony,” chronicled the career of an obscure 19th-century Russian paleontologist, Vladimir Kovalevsky, who died young after publishing just six scholarly papers between 1873 and 1877, but was the first to work out the evolution of horses.

Kovalevsky’s hapless life was marked by a marriage of convenience so that he and his wife, Sofya, a brilliant mathematician, could emigrate from Russia. They settled in Germany, where they lived and worked in different cities. After going broke from bad business deals, Vladimir, who suffered from mental illness, fell into a deep and prolonged depression and committed suicide in 1883 by putting a bag with chloroform over his head.

Among vertebrate paleontologists, however, Vladimir’s wondrous theory of horses evolving from many-toed ancient ancestors to a single-toed modern animal lived on as a classic of correlating evolution to a change in environmental conditions -- namely from soft swamps to hard plains.

Vladimir’s observations were championed by esteemed evolutionary biologists, including T.H. Huxley and Charles Darwin himself. After 45 minutes of prelude reading the essay, Gould told the audience with a gleam in his eye, “This is a literary device. I’m setting you up.”

In the essay’s concluding section, Gould turned the tables. “Vladimir was wrong,” he said, noting the Russian studied only European fossils, a peculiar side branch-horse species, while the real evolution of horses had occurred in America. Huxley and Darwin noted Vladimir’s wrong assumptions and went on to revise and build upon the obscure Russian’s groundbreaking, albeit flawed, research.

“It was a fruitful error,” Gould said. “It was a case of being right for the wrong reason, an eminently useful and wonderful mistake.” The moral of Gould’s story: “Great truth can emerge from a small error.”

Top of Page

Joyce Carol Oates spoke at the University at Albany on October 11, 1994 as part of the New York State Writers Institute's Visiting Writers Series. The following article by Claudia Ricci appeared in the Spring 1995 issue of Albany, the University's magazine.

She Leaves Readers Breathless

Her new 608-page novel (her 24th) was on bookstore shelves, and another, shorter novel was already at the publisher. She had notes for a play she was rewriting, and literally, “a drawer full of sketches and outlines” just waiting to come to life.

But when she visited the University at Albany last fall as a guest of the New York State Writers Institute, Joyce Carol Oates said she was between major projects. "My mind is sort of open," she said. "I feel very free, as if I am hoisting a sail and waiting for the wind to take it in some direction." For Joyce Carol Oates, that direction is almost impossible to predict. One of the most prolific writers of modem times, Oates has written in so many genres and on such a wide array of topics that she leaves readers breathless. Critics are often puzzled about how to categorize her. Oates's work ranges from gritty social realism to romance, from gothicism to gentle satire. How does one makes sense of her extraordinary output, her breadth, her ability to write with equal authority about auto racing and academia, boxers and suburbanites, migrant workers and girl gang members, intellectuals and inner city life?

Asked how her ideas arise, Oates talked about many influences: her own experiences, those of others, her voluminous reading, her memory, her research, her unconscious. In the end, though, the source of Oates's inspiration is as elusive, as hard to pin down, as her imagination itself. Inspiration, for Oates, is very much connected to the literal meaning of that word: the act of inhaling. Joyce Carol Oates inhales the world. And when she breathes out, she exhales the world in her writing. Indeed, in one of her early interviews, Oates admitted to a "Balzacian" desire "to put the whole world into a book."

Oates said she always begins a novel with characters, characters she knows "very well, very intimately" before she begins writing. Although fiction always incorporates some element of personal experience, be it as a "vision one has had, a description of a scene, or thoughts that fleetingly pass through the mind," Oates says her characters "tend to be fictional, or composites of people. Typically, to create a character, Oates combines herself with another person.

"It's a kind of a strange hybrid," she observed. "If I write about a man, as I do in my new novel, obviously this is a person antithetical to me. And yet it's as if I'm absorbed in him, so that there is him, but I'm also part of him, and my consciousness of what he's doing or what his life is transcends his own vision of himself." In effect, Oates is always just one step ahead of her characters, leading them through the events of their lives. "I'm guiding them. I know a little more than they do so when they see things they have a certain ironic cast. But it's as if I were combined with (the characters)." Oates believes that it is the lure of creating characters that inspires fiction writing. "I think that's why we all write," to gain access and insights into the emotions and experiences of others. "Each work of fiction is a window into another alternative universe," she said, "one that we are not in fact living but we might have been."

After Oates creates her characters, she then creates a structure for the novel, and sets the characters in motion. But at that point, a bit of magic takes over. "I'm like someone who's embarked upon a river journey, I really don't know what's going to happen," she said. "You know you're not going to go off the river, that the river has a certain course and you're going to follow the course, and you know your destination. But you don't know how you're going to get there." Stories, Oates says, even highly realistic narratives, frequently turn out to be re-enactments of ancient rituals or universal myths. "I think that there are rites being worked out in narratives of our own lives, but we don't recognize them necessarily," she said. "Sometimes one can write a whole novel or certainly a short story and not even realize it embodies a rite or ritual. Some mythic situation has been examined and dramatized without one's even being aware of it."

What are these mythic situations? "The most obvious story in human experience," Oates said, "has to do with evolution, with the drama of the generations, the rising of the young generation and the falling away of the older generation." This passage, Oates said, produces great turbulence, "turbulence that is greeted in each epoch with dismay, astonishment, anger and fear." Another example of an enduring ritual, she said, is the sacrifice of the savior and the rejuvenation of a community. "We see these sacrificial rites in all sorts of seemingly realistic novels, like those by Henry James or Edith Wharton. We certainly see them in Faulkner and I suppose they are in my own writing, too." Oates said she isn't conscious of inserting the mythic stories into her fiction. "It's not that I put these things deliberately in there, but still, I think I'm always writing about these areas of conflict. To me it seems very obvious that Darwinian evolution in personal history and cultural history is the underlying drama, whether anyone wants to acknowledge it or not. Nobody can say history stops with me because the oceans, the waves are just going to keep on moving and splashing and cresting and falling back and so forth. No one can stop them." Pressed for specifics about how she got her inspiration for her most recent novel, about a serial killer, Oates spoke of her fascination with the pathological personality of a serial killer, someone who loves to kill, who loves to torture, who feels no remorse about killing, no regrets about his actions except for the fact that he or she is caught. Another part of the inspiration arose from a series of news reports describing controversial experiments by the U.S. Department of Defense during the 1950s, in which government scientists gave boys at a school for the retarded outside Boston food laced with radioactive substances .

Oates, a tall, willowy figure with delicate hands and a sweet, high-pitched voice, said she found "an apt metaphor," a direct connection, between the fact that a serial killer feels perfectly justified in killing helpless victims and the fact the government felt justified in experimenting on helpless retarded boys in the 1950s.

The 160-page short novel that resulted from this metaphor took Oates only about eight weeks to write. But not all of her projects proceed so quickly and effortlessly. Oates says What I Lived For, the novel she published last fall, was the most difficult and laborious experience of her writing career. "I had many weeks of hell," she said, "many false starts," when she would begin the first chapter, and then, lacking the proper narrative voice, she would lose momentum and have to put the project aside. She accumulated about 1,000 pages of notes, "sketches for scenes, descriptions of characters, people talking," before she was able to begin writing in earnest.

Part of the reason What I Lived For was so difficult to write was the novel's length (608 pages) and because the events take place in only four days. "Everything is interlocked, so that almost every sentence, and certainly every paragraph, hooks into other points of the novel." Because she structured the book like "a great jigsaw puzzle," Oates said she couldn't write the first page until she knew what was going to be on the last page. "So I had to have it all in my head and memorized, in a sense, before I could start writing it at all." Another problem, Oates said, is that she felt the book should be a "very important novel," and that caused her considerable anxiety.

Oates tried and rejected a word processor because she found it too hypnotic. Instead, she minimizes anxiety by writing her first draft in long hand, setting her paragraphs down on long thin sheets of scrap paper (eight-and-a-half-by-eleven inch sheets, cut in half vertically). Later, she numbers the paragraphs, arranges them and puts them on a typewriter. "It's a wonderful way to write, very casual," she said. Using scrap paper, "you don't feel that it's anything too important or too significant."

Curiously, Oates usually feels relaxed between large projects. Anxiety starts to rise, she said, as soon as she gets inspired by a vision, a new project. "When I start work on a project that I consider important, I get extremely tense and tighter and tighter like a rubber band pulled very tight, so that's the state I find difficult." Over the years, Oates has changed the way she assembles a novel. Originally, she wrote a complete first draft, and then she went back and rewrote the manuscript. "I would work in sequence, in chronology, and then I would have that manuscript and then I'd go back and revise it."

Now, she revises as she goes along, continually rewriting "every paragraph, every page, every chapter, over and over again." Typically, Oates writes in the morning hours, sitting down at her desk as early as 5:30 a.m. In the afternoons, Oates may go out jogging or biking. Ironically, she produces almost as much writing when she's busy traveling and lecturing as she does when she has an open schedule. The key, she says, is efficiency. "Last summer when I had a complete day yawning before me I would be very slow getting started, and take a lot of time off. (But) when I don't have much time, well, then each minute is precious. So I get up a little earlier and I don't read the newspaper and I go immediately to my desk." The result? "I can almost get as much done when I'm very busy as when I'm not busy. You really only have a certain number of hours in the day when you can write."

Does Oates ever worry that the wellspring of her inspiration might dry up, that new ideas won't be there? No, she said, that really has never been a concern.

"I won't live long enough to execute all of my ideas," she said, referring back now to that drawer full of sketches she has, just waiting to be fleshed out. But she is nonetheless always casting about for something fresh, some new inspiration, "something," she said, "that takes my

breath away."

Top of Page

Shelby Foote:Fleshing Out the Stories of History

Shelby Foote:Fleshing Out the Stories of History

By Paul Grondahl, M.A.’84

Shelby Foote spoke at the University at Albany on March 20, 1997 as part of the New York State Writers Institute's Visiting Writers Series. The following article by Paul Grondahl appeared in the Fall 1997 issue of Albany, the University's magazine.

Shelby Foote was at the bar in an Albany restaurant, a Scotch in his left hand, an unlighted pipe in his right, arms extended to form the barrel of a rifle. He described in word and gesture for William Kennedy and anyone else who cared to listen how the famous Civil War commander of the Confederate Light Division, A.P. Hill, met his maker.

“Hill was on his horse, taking aim at enemy soldiers behind a tree and he said, ‘Let’s take ’em,’” Foote recalled, in a voice a writer once described as the sound of molasses over hominy, every muscle of Foote’s remarkably vital 80-year-old body acting out the fatal scene. “The ball ripped through Hill’s left thumb and lodged in his heart.”

Here, Foote paused for effect, as his listeners nudged a few inches closer, drawn in by the intimacy and power of his story, feeling as if the hot lead had just pierced their chests, too. “He was dead before he hit the ground,” Foote said.

His story done, the eminent Southern man of letters sidled off to a corner of Ristornte Paradiso to light up a bowl of his special blend tobacco and sip a Dewar’s on the rocks.

So it goes with Shelby Foote, acclaimed novelist and historian, who has, more than any other literary figure, given us the flesh-and-bones human story within the historical facts of the Civil War. “It’s become attractive to put a shine on that war and to forget there were more than one million casualties,” Foote told an audience of 600 people during his visit to the University in March as part of the New York State Writers Institute’s visiting writers series. “I don’t know how we’d do today under a great test like the Civil War. It seems like the nation might fly apart.”

Foote is best known for his three-volume historical masterwork, The Civil War: A Narrative. The volumes move with a novel’s immediacy and visual quality, as if Foote were in a bar, telling you what happened to all the characters as he acted out the battles. He had a lot of stories to tell the Albany audience about his Civil War trilogy, a project he likened to “swallowing a cannonball.” What Foote anticipated might be a four-year project turned into a three-volume Herculean effort that consumed two decades of his life, topping 1.6 million words and a total of 2,093 pages when published.

At an afternoon writing seminar before his public reading, Foote offered a simple motto that guides his writing, borrowed from a John Keats letter: “A fact is not a truth until you love it.”

The Keats quote offered a coda to Foote’s remarks, which addressed the general theme of the novelist as historian. Born in 1916 in Greenville, N.C., and a graduate of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, where he was a literary prodigy along with his classmate Walker Percy, Foote published several highly regarded novels — including Tournament (1949), Follow Me Down (1950) and Love in a Dry Season (1951) — before he turned to nonfiction. Foote believed learning the craft of storytelling, instead of simply training as a prodigious accumulator of historical fact, was critical to his tutelage as a writer.

“My point about writing history is that the facts must be told with the art of true narrative,” Foote said in his seminar, acknowledging he could be construed as attacking scholarly history texts. “The prose of academics is often so dismal that the footnotes are not an interruption, but a welcome relief.”

In his introduction to Foote’s reading, Kennedy, the Writers Institute director and founder and a Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist, put Foote’s writing in context. Kennedy talked of Foote, the precocious teenager, selling poems to magazines for 50 cents apiece, infatuated with his literary idols, Marcel Proust, William Faulkner and Walker Percy’s uncle, Will Percy. Foote started a novel in his late 20s, but World War II interrupted and Foote served in the European theater under General George Patton as a captain of field artillery. After the service, Foote returned to fiction and sold his first short story to the Saturday Evening Post in 1946. Then came a succession of novels before the first Civil War volume in 1958.

Kennedy noted that scores of television viewers were introduced to Foote during Ken Burns’s 1991 PBS series “The Civil War.” Looking like “a cross between Sigmund Freud and Robert E. Lee,” Foote’s insights “conveyed the subliminal authority of an eyewitness,” according to Charles Trueheart of The Washington Post.

With a thick head of silver hair, heavy-lidded eyes and craggy face framed by a beard and mustache, Foote stood before the large evening crowd in gray suit, white shirt and maroon tie and mesmerized his listeners by reading the epilogue to his Civil War masterpiece. “All things end,” he began, reading a 20-minute passage in a drawl that moved like the Mississippi River on a windless August afternoon. The powerful summary to Foote’s 2,093-page work ended thus: “Time plays its tricks . . . Memory smooths the crumpled soul. Did it not seem real? Was it not as in the old days?”

Foote was at his most captivating when answering audience questions or spinning impromptu yarns in response to comments.

How did he meet the great Faulkner, for instance? Foote was 19 years old and he and Walker Percy were planning to drive from Foote’s hometown, Greenville, Miss., through Faulkner’s town, Oxford, Miss.

Foote: “Let’s stop in Oxford and meet William Faulkner.”

Percy: “I’m not going to just knock on his door.”

Foote: “I will then.”

Percy: “Go ahead. I’m staying in the car.”

Foote recalled the walkway to Faulkner’s house was lined with cedar trees and he was greeted by three hounds, two fox terriers and a Dalmatian in the yard. Soon, a small man, shirtless and barefoot, naked save for a pair of shorts, and seemingly drunk, appeared and asked Foote what he wanted. “Could you tell me where to find a copy of Marble Faun, Mr. Faulkner?” Faulkner grunted for Foote to contact his agent. Faulkner was gruff and abrupt during that unannounced visit, but later befriended Foote, who walked Faulkner around the Civil War battlefields of Shiloh.

Driving Faulkner back to Oxford on one such outing, Foote, a precocious young novelist, announced to the acclaimed master: “You know, I have every right to be a better writer than you. Your literary idols were Joseph Conrad and Sherwood Anderson. Mine are Marcel Proust and you. My writers are better than yours.” Foote’s childhood milieu also helped him develop as a historical writer. “I’m from Mississippi and there’s very little to do there but be interested in history,” Foote said. “Our glory is in the past. I was an only child who did a lot of reading. I read a lot of Civil War books that were in our house and my great-grandfather had fought at Shiloh. He got the tail shot off his horse and came home.”

Foote said his writing, both fiction and nonfiction, is deeply informed by his geographical legacy. “Southerners have a sense of tragedy and we know defeat is waiting for us,” Foote said. “Vietnam didn’t come as a deep shock to Southerners. We had been whipped before and we had that perspective.”

Being a Southerner also gave Foote an appreciation for life’s paradoxes and complexity, past and present. “I love the Confederate flag, which my great-grandfather fought for and believed in,” Foote said. “It’s a sad thing because to my black friends, that flag represents extremely painful and horrible things. At one time, the flag stood for law and order and I regret it came into ill repute. Those racist Yahoos who wave the flag today know nothing about the Confederacy and what it stood for. I still wouldn’t take it down because I know what my great-grandfather fought for. It was right and yet it was wrong.

“This nation has two great sins on its very soul, as far as I’m concerned,” Foote continued. “The one is slavery. And we don’t know how we can ever wash that stain off. The other is emancipation. They told four million people to hit the road, you’re free. Three-quarters of them could not read or write. They did not have a trade. It was an outrageous form of emancipation. An utter disaster.”

Top of Page