| NYWI HOME PAGE | VISITING WRITERS & EVENTS INDEX | VIDEO ARCHIVES | NYS AUTHOR & POET AWARDS |

|

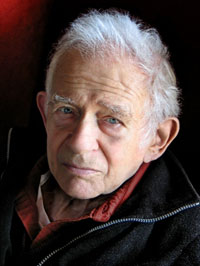

Two-time winner of the Pulitzer Prize

State Author 1991-1993

NYS Writers Institute, May 1, 2007

8:00 p.m. Reading | Page Hall, 135 Western Avenue

UAlbany's Downtown Campus

"A really great novel does not have something to say. It has the ability to stimulate the mind and spirit of the people who come in contact with it." - NM

Norman Mailer, a formidable presence in American letters for nearly six decades, is the author of novels, creative nonfiction, short stories, essays, and screenplays and an ex political candidate for Mayor of NYC and public persona who was born in Long Branch, New Jersey on January 31, 1923. In 1927 his family moved to the Eastern Parkway section of Brooklyn, where he attended P.S. 161 and Boys' High School. At the age of 16, he entered Harvard University to study aeronautical engineering. While at Harvard he developed an interest in writing. A short story, "The Greatest Thing in the World," which he wrote for the Harvard Advocate, won Story Magazine's college fiction prize.

| � |

Norman Mailer's first new novel in a decade is The Castle in the Forest (2007), a fictional chronicle of Adolf Hitler's boyhood. The book is narrated by Dieter, a devil assigned by Satan to nurture young Adolf.

"electrifying and peculiar.... This unforgettable novel by a master of prose reinforces the belief that we kid ourselves if we lay the blame for hideous crimes on one single individual, even if it is the devil. We are all culpable." - Beryl Bainbridge, Guardian (UK)

"'The Castle in the Forest'... about the young Adolf Hitler, his family and their shifting circumstances, is Mailer's most perfect apprehension of the absolutely alien. No wonder it is narrated by a devil. Mailer doesn't inhabit these historical figures so much as possess them." - Lee Siegel, New York Times

"compelling portrait of a monstrous soul." - Publishers Weekly (starred review)

A cultural icon since the 1950s, his name is mentioned in the Woody Allen movie "Sleeper" (1973), the John Lennon song "Give Peace a Chance," and in various songs by Simon and Garfunkel, the Red Hot Chili Peppers, Warren Zevon and GWAR. A perennial candidate for the Nobel Prize in Literature, Mailer received the Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters of the National Book Foundation in 2005.

A cultural icon since the 1950s, his name is mentioned in the Woody Allen movie "Sleeper" (1973), the John Lennon song "Give Peace a Chance," and in various songs by Simon and Garfunkel, the Red Hot Chili Peppers, Warren Zevon and GWAR. A perennial candidate for the Nobel Prize in Literature, Mailer received the Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters of the National Book Foundation in 2005.

Mailer was inducted into the army in March 1944, less than a year after graduating with honors from Harvard with a B.S. in engineering. His experience in the army as a surveyor in the field artillery, an intelligence clerk in the cavalry and a rifleman with a reconnaissance platoon in the Philippine mountains, gave him the idea for a novel about World War II. Shortly after his discharge he began writing The Naked and the Dead which was published in 1948. The novel, a critical and commercial success, was at the top of the New York Times best-seller list for eleven weeks, and brought Mailer immediate recognition as one of America's most promising writers. The Naked and the Dead remains one of the classic novels of World War II and of the "New Journalism" genre.

Mailer's next two novels Barbary Shore (1951) and The Deer Park (1955), which was rejected by six publishers before being accepted, were not well received, and he turned his literary energies to journalism. He helped found The Village Voice in 1954 and wrote a weekly column for it for a short time. In 1959, Mailer published Advertisements for Myself, a collection of essays, letters and fictions on the subjects of politics, sex, drugs, his own writing, and the works of others. It received considerable attention as it contained autobiographical passages of the pressures of success, money, liquor, and the literary marketplace on the serious American writer.

Mailer returned to the novel with the publishing of An American Dream (1965), and Why Are We in Vietnam? (1967), which was nominated for a National Book Award. During the 60s he also developed a hybrid literary form, combining fiction and nonfiction narrative in The Armies of the Night (1968) which won both the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award and brought Mailer both popular and critical acclaim, and Miami and the Siege of Chicago (1968), which won a National Book Award for nonfiction. In The Armies of the Night he used the techniques of a novel to explore an October 1967 anti-Vietnam march on the Pentagon, a protest during which he was arrested.

During the next ten years, Mailer continued to write prolifically, publishing a wide range of books including Of a Fire on the Moon (1971), a book on the Apollo II moon landing; The Prisoner of Sex (1971), an essay in response to the women's liberation movement; Marilyn (1973), a novel biography of Marilyn Monroe; The Fight (1976), a book-length description of the Muhammad Ali-George Foreman fight in Zaire, Africa, among others. His body of work displays a wide scope, a willingness to explore controversial themes and to experiment with different forms and styles.

Mailer returned to a book of the same intense proportions as The Naked and the Dead with The Executioner's Song (1979), a nonfiction novel on the life and execution of convicted murderer Gary Gilmore. The Executioner's Song won Mailer his second Pulitzer Prize and it also was nominated for the American Book Award and National Book Critics Circle Award. All reviews lauded Mailer's artistry and agreed that The Executioner's Song was a substantial book produced by a literary master.

Long promising an epic multi-volume novel of major importance, Mailer published Ancient Evenings, a work of mythic themes, in 1983. Billed as the first of a two-to-four part cycle, Ancient Evenings, an ambitious and daring work of fiction, is set in Egypt during the nineteenth and twentieth dynasties (1290-1100 B.C.).

In addition to his books, Mailer also has written, produced, directed and acted in several films. Wild 90 (1967), which Mailer produced and directed was an adaptation of his book The Deer Park. Despite terrible reviews, it ran for four months at New York's Theatre de Lys. His second film, Beyond the Law (1968) received positive reviews but did not draw audiences, and his third film, Maidstone (1971), based on The Armies of the Night received mixed reviews. He returned to the cinema to write a screenplay for his murder mystery novel of the same name, Tough Guys Don't Dance and to direct it himself . This film was well received at the 1987 Cannes film festival. Mailer also wrote the script for the film version of The Executioner's Song and received an Emmy nomination for best adaptation.

Harlot's Ghost, which was published in the fall of 1991. At 1,310 pages, it is a work of epic proportion and ambition about the people and the plottings of the C.I.A. during the crucial decades of the "American Century."

Books by Norman Mailer:

SELECTED FICTION

SELECTED FICTION

THE NAKED AND THE DEAD. New York: Rinehart, 1948.

BARBARY SHORE. New York: Rinehart, 1951.

THE DEER PARK. New York: Putnam's, 1955.

AN AMERICAN DREAM. New York: Dial, 1965.

THE SHORT FICTION OF NORMAN MAILER. New York: Dell, 1967.

WHY ARE WE IN VIETNAM? New York: Putnam's, 1967.

THE EXECUTIONER'S SONG. Boston: Little, Brown, 1979.

ANCIENT EVENINGS. Boston: Little, Brown, 1983.

TOUGH GUYS DON'T DANCE. New York: Random House, 1984.

TOUGH GUYS DON'T DANCE. New York: Random House, 1984.

HARLOT'S GHOST. New York: Random House, 1991.

THE GOSPEL ACCORDING TO THE SON. New York: Random House, 1997.

THE CASTLE IN THE FOREST. New York: Random House, 2007.

SELECTED NONFICTION AND COLLECTIONS

THE WHITE NEGRO. San Francisco: City Lights, 1957.

ADVERTISEMENTS FOR MYSELF New York: Putnam's, 1959.

CANNIBALS AND CHRISTIANS. New York: Dial, 1966.

CANNIBALS AND CHRISTIANS. New York: Dial, 1966.

THE ARMIES OF THE NIGHT. New York: New American Library, 1968.

MIAMI AND THE SIEGE OF CHICAGO. New York: New American Library, 1968.

OF A FIRE ON THE MOON. Boston: Little, Brown, 1970.

THE PRISONER OF SEX. Boston: Little, Brown, 1971.

THE FAITH OF GRAFFITI. New York: Praeger, 1974.

THE FIGHT. Boston: Little, Brown, 1975.

THE EXECUTIONER'S SONG. Boston: Little, Brown, 1979.

OSWALD'S TALE: AN AMERICAN MYSTERY. New York: Random House, 1996.

WHY ARE WE AT WAR?. New York: Random House, 2003.

BIOGRAPHY [IN NOVEL FORM]

MARILYN. New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1973.

SELECTED RESOURCES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

NORMAN MAILER: A COMPREHENSIVE BIBLIOGRAPHY compiled by Laura Adams.Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press, 1974.

BIOGRAPHY

MAILER: A BIOGRAPHY by Hilary Mills. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1984.

CRITICISM

NORMAN MAILER by Richard Poirier. New York: Viking, 1972.

CRITICAL ESSAYS ON NORMAN MAILER compiled and introduced by J. Michael Lennon. Boston: G. K. Hall & Co., 1986.

RADICAL FICTIONS AND THE NOVELS OF NORMAN MAILER by Nigel Leigh. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1990.

From the Works of Norman Mailer:

"Ron Stanger's first impression was how many people were in the room. God, the number of spectators. Executions must be a spectator sport. It really hit him even before his first look at Gary, and then he was thankful the hood was not on yet. That was a relief. Gilmore was still a human being, not a hooded, grotesque thing, and Ron realized how he had been preparing himself for the shock of seeing Gary with his face concealed in a black bag. But, no, there was Gary staring at the crowd with an odd humor in his face. Stanger knew what he was thinking. 'Anybody who knows somebody is going to get an invite to the turkey shoot."' - from The Executioner's Song

"One of the oldest devices of the novelist--some would call it a vice--is to bring his narrative (after many an excursion) to a pitch of excitement where the reader no matter how cultivated is reduced to a beast who can pant no faster than to ask, 'And then what? Then what happens?' At which point the novelist, consummate cruel lover, introduces a digression, aware that delay at this point helps to deepen the addiction of his audience.

This, of course, was Victorian practice. Modem audiences, accustomed to superhighways, put aside their reading at the first annoyance and turn to the television set. So a modem novelist must apologize, even apologize profusely, for daring to leave his narrative, he must in fact absolve himself of the charge of employing a device, he must plead necessity." - from The Armies of the Night

"But this frustration was replaced by another. What if he had been present, had directed the climactic day himself? What really would it have meant? The Japanese had been worn down to the point where any concerted tactic no matter how rudimentary would have been enough to collapse their lines. It was impossible to shake the idea that anyone could have won this campaign, and it had consisted of only patience and sandpaper.

For a moment he almost admitted that he had had very little or perhaps nothing at all to do with this victory, or indeed any victory--it had been accomplished by a random play of vulgar good luck larded into a causal net of factors too large, too vague, for him to comprehend. He allowed himself this thought, brought it almost to the point of words and then forced it back. But it caused him a deep depression."

- from The Naked and the Dead

"He did not, said Kittredge. He had died in the hospital."

That may have been his end, but since I had thought of him as near to dead for many years, I pondered his slow extinction. Had his soul died years before his heart and liver and lungs? I hoped not. He had enjoyed so much. Espionage had been his life, and infidelity as well; he had loved them both. Why not? The spy, like the illicit lover, must be capable of existing in two places at once. Even as an actor's role cannot offer its reality until it is played, so does a lie enter existence by being lived." - from Harlot's Ghost

For additional information, contact the Writers Institute at 518-442-5620 or online at https://www.albany.edu/writers-inst.