|

New York state of mind

Kurt Vonnegut, the voice and vision behind 'Slaughterhouse Five' and many more novels, is the latest State Author

Kurt Vonnegut has been summarily unimpressed with the protracted presidential election imbroglio. For the past six weeks, much of the nation has been mesmerized by stop-and-go go-and-stop vote counts, hanging and dimpled chads. But not the prolific author famous for his irreverent wit and dark satire.

|

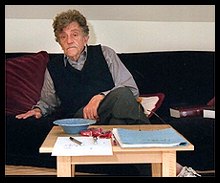

STACEY LAUREN / TIMES UNION Author Kurt Vonnegut sits in his Northampton, Mass., apartment. In front of him is a blue floder labeled "Novel."

|

|

"It's all an electronic tantrum, just like O.J. was. That's what this whole mess is,'' Vonnegut said with a dismissive wave of his left hand, smoke wafting in front of his craggy face from an unfiltered Pall Mall cradled in his fingers."Of course it's more than that,'' he added, "but just once I'd like to turn on the TV or radio and find out what's going on in the rest of the world. Hell, I'd like to know what's going on in my life.'' A writer who also bears the mantle of celebrity -- Discover Card recruited him for an advertising campaign; a Massachusetts brew pub named one of its beers after him -- Vonnegut will for the next two years also be known as the State Author for New York, an honor that Gov. George Pataki will officially bestow upon him next month at a ceremony in Albany. He succeeds the novelist James Salter. For most of this year, though, the 78-year-old writer best known for the 1969 anti-war book "Slaughterhouse Five'' (ranked 18th of the Modern Library's top 100 English-language novels of the 20th century) has been living in a spacious studio apartment in Northampton, Mass., where he is teaching advanced writing at Smith College. He came to this thriving, picturesque New England town to heal as much as to inspire young students. Vonnegut was not in a good way when he arrived in Northampton in the spring. He was weak and out of sorts, the aftereffects of a Jan. 31 fire in his East Side Manhattan brownstone. The structural damage from the fire -- caused by a spilled ashtray -- was limited to the top floor of the building, but most of Vonnegut's clothes were lost and his archives were destroyed. The one-time volunteer with the Alplaus Fire Department suffered smoke inhalation trying to extinguish the blaze and was initially listed in critical condition. He was hospitalized for four days. "I was a wreck after the fire. It seemed the best thing to do was come up here, where my daughter and nephews could take care of me. "Now I'm thinking about suing the makers of Pall Mall,'' he added, a devilish gleam in his eyes. "On the package they promise to kill me and they still haven't done it.'' His raspy laugh follows the oft-told line. Telling stories

A fourth-generation German-American from Indianapolis, Kurt Vonnegut Jr. stepped outside the family mold when he decided to make a living with words instead of blueprints. Both his father and his father's father were prominent architects. His mother was the daughter of millionaire and Indianapolis brewer Albert Lieber. Vonnegut's high school did something almost unheard of today: It published a daily newspaper, The Echo. It was where he got hooked telling stories. "We weren't writing for the teachers, we were writing for our peers,'' he recalled. "We found out right away if our stories were any good or not.'' When he arrived at Cornell University in 1940, writing for the college's weekly paper seemed almost too easy compared to the excitement of his daily experience at Shortridge High School. Soon, a bigger adventure beckoned: World War II. Even though he considered himself a pacifist, Vonnegut left college in January 1943 to enlist in the Army. "The First World War was about absolutely nothing, but then a just war came along,'' he said. "I was young and in good health and I was ready for it. I wouldn't have missed it for anything.'' His infantry division was stationed on the German border, assigned to deplete Hitler's forces. There were countless casualties when the Germans attacked in December 1944. Vonnegut was captured and taken prisoner. He spent the next five months in Dresden and was there during the heaviest Allied bombing raids. "I was born hating war, I think. I never thought war was a good idea,'' Vonnegut said. "But the second World War had to be fought, and I was proud to have fought in it. Civilization was in terrible danger and blood had to be shed to save it.'' The experience gave Vonnegut material for "Slaughterhouse Five'' and other books, but he did not immediately start writing fiction when the war ended and he was freed. He married his childhood sweetheart, Jane Cox, and returned to newspapers, covering police and crime in Chicago. The GE years

His older brother, Bernard, a scientist with General Electric, helped recruit him to come to the Capital Region. From 1947 to 1950 Vonnegut lived in the Schenectady County hamlet Alplaus and was a public relations writer for GE. "Believe it or not, GE was a wonderful company to work for, and we had genuine news to report, good news for the world,'' Vonnegut said. "I was proud to work for GE. The only reason I left was that I could make more money writing short stories.'' Vonnegut is appalled by the position GE has taken today with the controversy over dredging the Hudson River to remove PCBs that GE deposited there a quarter-century ago. "We would have handled it different, to be sure. We would have gotten the story out about how ashamed and sorry GE is and the company would have done everything it could to fix this mess.'' Bernard, who died in April 1997 at age 82, would spend the rest of his life in the Capital Region. He was recognized internationally for his part in the discovery of cloud-seeding techniques and spent much of his career at the University at Albany's Atmospheric Sciences Research Center. Kurt had his brother cremated and his ashes scattered over Mount Greylock in the Berkshires, where Bernard had first experimented with cloud-seeding by tossing salt from a twin-prop plane in an effort to determine what caused precipitation. After Vonnegut realized he could make a living writing stories, his own nuclear family moved to Cape Cod. They had three children -- including Nanny, now an artist in her 40s in Northampton -- and adopted his sister's three children after she and her husband died within days of each other. Prolific period

The next two decades were the most prolific period of Vonnegut's life. His short stories were regularly featured in Saturday Evening Post and other magazines. During that time he published a half-dozen novels that are among his most acclaimed: "Player Piano,'' 1952; "The Sirens of Titan,'' 1959; "Mother Night,'' 1961; "Cat's Cradle,'' 1963; "God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater,'' 1965; and "Slaughterhouse Five,'' 1969. He was, he says now, striking while the iron was hot. Most writers produce their best work before they are 40, Vonnegut says, adding there are virtually no "old men'' writing good books of fiction. His most recent novel was "Timequake,'' published in 1997. He wonders if it will be his last. "I don't know,'' he said. "I didn't expect to live this long. What's interesting is Saroyan, Hemingway, Steinbeck, during their 20s and 30s, they wrote better than they had any right to. That stops. "I look back now and wonder, 'How in the hell did I do that?' That's all over now.'' Asked if he considers himself a great writer, Vonnegut shakes his head right away, his unruly thatch of gray-brown hair bobbing. "I consider myself remarkably successful, because most people fail,'' he said. "How can anyone consider himself or herself a great writer when there was William Shakespeare? The greatest ever American writer was Melville, but 'Moby Dick' wasn't appreciated until 38 years after his death.'' In 1970, Vonnegut separated from his wife and moved into the Manhattan town house near the United Nations building that is his primary address today. He has also had a house in the Hamptons on Long Island for more than 20 years. Vonnegut and Cox were officially divorced in 1979, and in November of that year he married photographer Jill Krementz. Three years later they adopted a girl, Lilly, who is a high school senior living in Manhattan with her mother while Vonnegut spends the school year in Northampton. He said he was looking forward to spending Christmas with them. Humanist at home

His studio apartment near Smith College is decorated with children's artwork, as well as paintings and drawings that he did himself. "It's something to do,'' he said, "like golf or playing bridge or anything else. My family, we're in the art business.''

On the counter separating the kitchen and living room is a bumper sticker: "Your planet's immune system/Is trying to get rid of you.'' Since 1992 Vonnegut has been the honorary president of the American Humanist Association, succeeding Isaac Asimov, the late science fiction writer. The politically progressive organization, based near Buffalo in Amherst, has roughly 5,000 members and publishes a bimonthly magazine. It advances a philosophy of reason and compassion that is not traditionally religious, according to Fred Edwards, editor of The Humanist. Said Vonnegut: "We try to behave as well as possible without any fear of any rewards or punishment in an afterlife. Historically, we've been very good citizens. We exist to let politicians know we're around. We believe in a strong separation of church and state.'' He insists he is a Luddite. When he gave an address at Smith in October, Vonnegut inveighed against the Internet and society's increasing reliance on computer interaction. He said, "I won't use the Internet, which is a particularly habit-forming, hallucinatory, pernicious form of LSD.''

|

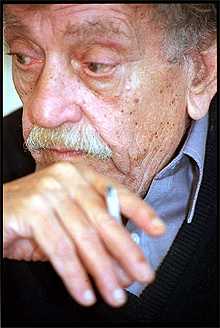

STACEY LAUREN / TIMES UNION Vonnegut talks about the election, dredging the Hudson and writing in his Northampton, Mass., apartment.

|

|

Yet he admits to owning and using an Apple Powerbook and admires its word-processing capability. An easy choice

Author William Kennedy, director of the New York State Writers Institute, which selects the State Author on behalf of the Legislature, says Vonnegut was an easy choice for the four-judge panel, which included himself and three other authors, Jayne Anne Phillips, George Plimpton and Salter, the current honoree. "Kurt was probably the most famous writer in the world at one point,'' Kennedy said. "He's endured, of course, because of his wit and his humanity as a writer. "His irreverence and his wit were hand in hand with the dropout society, with the hippies and the yippies. He was in all of their corners. He's transcended any momentary cult fadishness, of course. Kurt's a writer for many ages.'' Yet Vonnegut struggles with writing today. Sitting on the plain wooden end table that he has placed in front of himself as he sits on the couch is a tattered blue paper folder. Written in dark blue ink on the cover is one word: Novel. Next to the folder are a larger ceramic ashtray and a cherry red Zippo lighter. The Pall Malls are in his right pocket. "Everybody should write to find out who they are and where they are,'' he said. "Right now, though, I'm thinking I want to turn the typewriter into a musical instrument because I can really play it. I do finger exercises in the morning and hope something else will come out.''

|