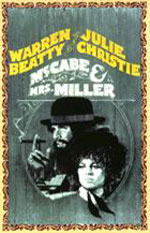

FILM NOTES

(United States, 1971, 120 minutes, color, 35mm)

Directed by Robert Altman

Cast:

Warren Beatty . . . . . . . . . . John Q. McCabe

Julie Christie . . . . . . . . . . Constance Miller

Shelley Duvall . . . . . . . . . .Mrs. Coyle

Keith Carridine . . . . . . . . . . Cowboy

The following appeared in a review by Roger Ebert in the Chicago Sun-Times, November 14, 1999:

It is not often given to a director to make a perfect film. Some spend their lives trying, but always fall short. Robert Altman has made a dozen films that can be called great in one way or another, but one of them is perfect, and that one is "McCabe & Mrs. Miller" (1971). This is one of the saddest films I have ever seen, filled with a yearning for love and home that will not ever come—not for McCabe, not with Mrs. Miller, not in the town of Presbyterian Church, which cowers under a gray sky always heavy with rain or snow. The film is a poem -- an elegy for the dead.

Few films have such an overwhelming sense of location. Presbyterian Church is a town thrown together out of raw lumber, hewn from the forests that threaten to reclaim it. The earth is either mud or frozen ice. The days are short and there is little light inside, just enough from a gas lamp to make a gold tooth sparkle, or a teardrop glisten. This is not the kind of movie where the characters are introduced. They are all already here. They have been here for a long time. They know all about one another. A man rides into town through the rain. He walks into a saloon, makes sure he knows where the back door is, goes out to his horse again, comes in with a cloth, and covers a table. The men are pulling up chairs before he has settled down. He is a gambler named McCabe (Warren Beatty). Somebody thinks they heard that McCabe once shot a man. In the background, somebody is vaguely heard asking, "Laura, what's for dinner?"

This is the classic Altman style, which emerged full-blown in "MASH" and can be seen in "3 Women," "Thieves Like Us," "Nashville," "California Split," "The Long Goodbye," "The Player," "Cookie's Fortune" and all the others. It begins with one fundamental assumption: All of the characters know each other, and the camera will not stare at first one and then another, like an earnest dog, but is at home in their company. Nor do the people line up and talk one after another, like characters in a play. They talk when and as they will, and we understand it's not important to hear every word; sometimes all that matters is the tone of a room.

The town of Presbyterian Church is almost all male, and most of the men are involved in building the town. It looks like a construction site, holes half-dug, lumber piled up waiting to be used, an old painted door joined to a raw new frame. Apart from work, there is nothing to do but drink, gamble and hire the pleasures of women. McCabe takes his winnings and purchases three fancy women -- not as entertainment, as an investment.

They're not too fancy; one is fat, one has no teeth, they all look scrubbed with too much cheap soap. His plan is to open a whorehouse and saloon, with a bathhouse in the back.

Mrs. Miller (Julie Christie) arrives in town and wants to become his partner. She is a Cockney who has long since ceased to be interested in her own beauty, except for what it will earn her. She explains to McCabe that he knows nothing of women, cannot see through their excuses, cannot quiet their fears or see them through female troubles, does not even know enough to keep the whole town from being clapped out within a week. She will import some classier women from San Francisco. They will do better than he can do on his own. He has to agree.

We get to know them in half-seen, half-heard moments. There is a time when he gets into bed with her and we realize with a start that the movie has not established that they are sleeping with one another. Later it doubles back to reveal that she charges him, just like all the others. She gets $ 5, top price. McCabe spends a lot of time talking to himself, muttering criticisms and vows. He says to himself what he would like to say to her: "If just one time you could be sweet without money to it." And, "I got poetry in me!" His soliloquies are meandering, rueful, oblique. His most sustained burst of conversational energy is a joke he tells about a frog; he does it in dialect, and I think it's a private joke, since he sounds uncannily like Gene Hackman's character Buck in "Bonnie and Clyde."

…All of this unfolds mostly indoors, in dark rooms lit by lanterns and log fires. Episodes are punctuated by Leonard Cohen songs, sad frontier laments. The cinematographer, Vilmos Zsigmond, embraces the freedom of the wide-screen Panavision image (this was before screens got narrower again to accommodate home video). He drowns the characters in nature. It is dark, wet, cold, and then it snows. These are simple people. There is a moment when two couples are dancing to a music box in the whorehouse parlor. It comes to the end of a tune, and all four cluster around the box, bending low, peering at its mechanism, poised in suspense. The next tune begins and they spring up, relieved, to dance again.

…Snow falls steadily all through the closing passages of the film. There is no musical soundtrack, apart from the Cohen songs. McCabe is tracked through the town by three hired killers, including the young gunslinger. The snow falls so heavily, blowing at a slant, it is like unheard music.

The following appeared in a review by Charles Taylor in Salon, March 21, 1997:

In the opening shots of Robert Altman's "McCabe & Mrs. Miller," the camera follows John McCabe (Warren Beatty) making his way on horseback through the green-brown hills of the Pacific Northwest. As the camera pans slowly to the right, it picks up the credits, hanging in the rain-soaked air. They don't fade in, as most credits do. Like everything else in "McCabe & Mrs. Miller," they seem to have existed before we took our seats in the theater, before Altman started filming.

"McCabe & Mrs. Miller" is a western that, as shot by Vilmos Zsigmond, looks like old photographs lit from within, as though the subjects had created a sort of afterlife by finding a way to project their essence onto the film. The movie haunts you like a ballad whose tune you remember but whose words hang just beyond reach. And like listening to a ballad, we know the outcome of the events we're watching was foretold long ago, but we're helpless to do anything but surrender to the tale.

McCabe, a romantic fool who fancies himself a big shot, is a gambler who dreams that his fortune lies in bringing a saloon and a whorehouse to the mining town of Presbyterian Church. His business partner, Mrs. Miller (Julie Christie), is a hard-headed madam with dreams of her own, the ones emanating from her opium pipe. The movie feels as delicate, as lulling, as Mrs. Miller's drug-induced visions, and yet the life it shows us, the town and its people, are so real and sturdy we seem to have stumbled on them. The life the movie shows us is already being lived by the time we turn up. And everything we encounter evolves naturally—the setting, the characters, the story and most of all the mood.

"McCabe & Mrs. Miller" is beautifully, overwhelmingly sad, the sort of romantic sadness you can fold around you like the bearskin coat McCabe envelops himself in. The melancholy is there even when you're laughing at the conversations Beatty (who gives the sort of performance that makes you fall in love with an actor) conducts with himself; when McCabe is assuaging his longing for Mrs. Miller by paying $5 for a night with her; even when hired guns come to town to force him to sell his interest.

For me, "McCabe & Mrs. Miller" is the standard for a sort of emotional purity, a movie whose feeling permeates you without ever once forcing a thing. Emerging from it, I always feel like the town drunk who attempts a jig on the ice in one scene: drugged, unsure of my footing, as if one step would send the whole enterprise crashing to the ground. I try to clutch the images to me even as they seem to evaporate like smoke. Like all things that are beautiful and unalterably sad, "McCabe & Mrs. Miller," by its final scene—the hired guns tracking McCabe through a quiet, persistent blizzard—achieves a deep sense of peace. Your heart is breaking, but you can't help being struck by the loveliness of the snow that, like Joyce's, settles over all the living and the dead.

For additional information, contact the Writers Institute at 518-442-5620 or online at https://www.albany.edu/writers-inst.

McCabe & Mrs. Miller

McCabe & Mrs. Miller