FILM NOTES

FILM NOTES INDEX

NYS WRITERS INSTITUTE

HOME PAGE

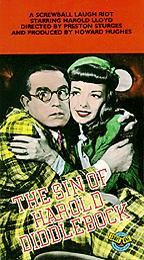

(American, 1947, 100 minutes, b&w, 16mm)

Directed by Preston Sturges

Cast:

Harold Lloyd . . . . . . . . . . Harold Diddlebock

Frances Ramsden . . . . . . . . . . Miss Otis

Jimmy Conlin . . . . . . . . . . Wormy

Edgar Kennedy . . . . . . . . . .Bartender

With Jackie the Lion

The

following film notes were prepared for the New York State Writers

Institute by Kevin Jack Hagopian, Senior Lecturer in Media Studies

at Pennsylvania State University:

It's the big game for little Tate College. Cheerful, energetic, dogged Harold Lamb is warming the bench for the Tate eleven, but he gets his chance when the team suffers a streak of casualties. Plucky Harold gets in the game, and, through a series of trick plays, wins the game, the girl, and the glory. Likeable schlemiel Harold is transformed into the biggest man on Tate's little campus. Presumably, Harold's next four years are a happy montage of homecoming dances, more successes on the gridiron, University Players Revues, good-natured hazing of underclassmen, all of it ending with a segue into graduation day accompanied by the old song "You gotta be a football hero..." played on the ukulele and sung by the College Glee Club. Harold is a king, Tate's leafy campus his empire, and the ivy on its buildings his laurels.

Such would be the stuff of football on the screen from HARMON OF MICHIGAN to FORREST GUMP, but Harold Lloyd's delightful 1924 THE FRESHMAN wrote the playbook. It was one of the great silent screen comic's biggest hits, ranked by fans and critics alongside his other masterworks, SAFETY LAST and THE KID BROTHER.

Writer/director/producer Preston Sturges was the comic wunderkind of his own era, the early 1940's, and he loved Lloyd's football fantasy for its good-heartedness and brilliant comic logic. But Sturges was also curious about the darker face of the American Dream, and he wondered: what would Harold's life be like after he hung up his cleats, when his triumphs on the fields of Tate College were just a heap of yellowing newspaper clippings? The result was a project he originally called "The Saga of Harold Diddlebock," a film that starts where THE FRESHMAN ends, and stars none other than Harold Lloyd himself in a tour de force of his own screen character from the 1920's, gone paunchy and fleabitten in the 1940's.

At the end of World War II, the project appealed to Harold Lloyd. He recognized Sturges as a comic talent to rival his own. In addition, he appeared in a film since 1938's PROFESSOR BEWARE (though he had produced two films for RKO Pictures), and was eager to get back in front of the camera. Lloyd was perhaps the richest of all the silent screen stars; his films had made more money than those of any other single performer during the 1920's, including his rival, Charlie Chaplin, and he lived in the most impressive mansion ever built in Hollywood, the vast Greenacres, with its own 9-hole golf course. But Lloyd's passion for filmmaking was unabated, and he thought that an alliance with Sturges would put him back on top.

Sturges, for his part, was embarking on what he thought would be the most important phases of his career. After making a string of the finest comedies in American screen history at Paramount, including THE LADY EVE and SULLIVAN'S TRAVELS, Sturges had found what he believed was the greatest measure of independence possible with a deal to make films for California Pictures, a production company established for him by Howard Hughes. THE SAGA OF HAROLD DIDDLEBOCK was to be his first project for California Pictures.

From the start, there was friction. Sturges was fascinated by the gloominess of the premise, a man stuck in a rut of remembering for twenty years. He retitled the film THE SIN OF HAROLD DIDDLEBOCK to focus attention on Harold's taking his first drink, and the mayhem that proceeds from it, and he wanted the film to be another of the fast-paced dialogue comedies he'd become known for. But Lloyd was adamant; he wanted to include more comic business and bits, and he pointed out that Sturges had chosen him because of his silent films. The two reached a weird compromise: the film would have everything in it. Because Lloyd's contract stipulated that he would have to be satisfied with the approach Sturges was taking, they actually shot two versions of many scenes. In the first version, Sturges was in control, emphasizing dialogue and story, and in the second, Lloyd's version, the scene was built on comic routines and emphasized simple character traits at the expense of any notion of a "saga." They screened the two versions together, and picked whichever seemed the best approach for that scene. What resulted is one of the most manic enterprises ever put on the American screen, a non-stop marathon of bits, shtick, and gags woven into a narrative so fast-paced it sometimes seems like an amphetamine jag. Lloyd and Sturges both loved physical comedy and pratfalls, but they discovered that they had two competing philosophies about the use of comedy: Lloyd believed that a film had to build sympathy for the leading character, so that when he was put in jeopardy in the comic moments, the audience would feel a melodramatic involvement with him. Sturges, on the other hand, as Lloyd's astute biographer Tom Dardis put it, believed in treating his comic protagonist "as a half-mad dolt, caught up in a whirlwind of chance events." As a result, the film lurches from one explosive moment to another. One of its several climaxes, and the most famous, comes when (somehow) Harold and a confidante character named "Wormy," played by Sturges veteran Jimmy Conlin, find themselves escorting a lion on an errand to a Wall Street banker. Next to Harold and Wormy's eccentric playing and the bizarre physical comedy of this chase sequence, the Three Stooges look like Noel Coward.

Not surprisingly, given its schizophrenic style of production, the film ran hugely over budget, its 64 day shooting schedule ballooning to 116 days. The film's reception was a lukewarm one, for, though everyone was glad to see Harold Lloyd up to his old comic tricks again, the absurdity of the action and the dour tone of Harold's character were a radical change from the well-engineered, sentimental films Harold had made in the 1920's. Howard Hughes, who had nothing better to do with his time, pulled the film from distribution, cut it in a way that managed to make it even less than coherent, and re-released it as MAD WEDNESDAY. The film failed again, and was retired to an ignominious early sale to television, where its antic characters and anarchic plot won it many converts. Lloyd was guaranteed a high salary for making the film, but it ended his career; he would never star in a film again. For Sturges, the HAROLD DIDDLEBOCK affair began one of the most painful eclipses in American film, one which end with his premature death after many failed projects. THE SIN OF HAROLD DIDDLEBOCK became a film discussed with a wagging of the head, an object lesson in what happens when two geniuses collide, an alleged artistic disaster. The only trouble with this take on the film was that it was usually an opinion voiced by deep-dish critics who hadn't actually seen the film. For a better perspective, they should have consulted the legions of adolescents who thought the film great fun, and who sensed an incisive jab at the American success ethic lurking just beneath the sadistic humor of the film.

Yes, the comic sequences do seem unmotivated, and yes, Harold's character has a seediness never seen in his silent films. But these are virtues in a film that often seems to presage Ionesco and the best comic moments of the Theater of the Absurd. And salted throughout THE SIN OF HAROLD DIDDLEBOCK are scenes that are flat-out some of the funniest moments in American film comedy. A late-night television screening of THE SIN OF HAROLD DIDDLEBOCK on a New York station years ago was the occasion of the first time I actually fell out of my chair laughing at a movie. I can't help but think that Harold Lloyd would have appreciated the gesture. So might Preston Sturges, but only if I'd hurt myself.

— Kevin Hagopian, Penn State University

For additional information, contact the Writers Institute at 518-442-5620 or online at https://www.albany.edu/writers-inst.

The Sin of Harold Diddlebock

The Sin of Harold Diddlebock