FILM NOTES

FILM NOTES INDEX

NYS WRITERS INSTITUTE

HOME PAGE

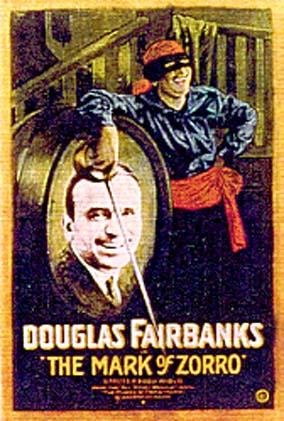

(United States, 1920, 90 minutes, b&w, 16mm, silent)

Directed by Fred Niblo

Cast:

Douglas Fairbanks, Sr . . . . . . . . . . Don Diego Vega/Zorro

Marguerite De La Motte . . . . . . . . . . Lolita Pulido

Noah Beery . . . . . . . . . .Sgt. Gonzales

LIVE PIANO ACCOMPANIMENT PROVIDED BY MIKE SHIFFER

The

following film notes were prepared for the New York State Writers

Institute by Kevin Jack Hagopian, Senior Lecturer in Media Studies

at Pennsylvania State University:

"The man that’s out to do something has got to keep in high gear all the time." - Douglas Fairbanks

Douglas Fairbanks was perfectly a man of his time. No other star, ever, has so exemplified what so many Americans wanted to believe were their own traits. If you were an adult in Fairbanks’ day, the nation, urbanized and frenetic, was a radically different place from the slower, more pastoral place you'd grown up in. Cars and radio and the stock market and war -- America had grown to be a daunting place in the early 20th century. On the screen, Fairbanks, with his (still, to this day) astounding athleticism, his ferocious bonhomie, and his evident disinterest in taking anything seriously, said to Americans that their world merely seemed complicated; actually, it was just an apple ripe for the picking. Fairbanks promised command without conquest, joy through strength. When he put his arms at his waist and tossed back his head to have a laugh at it all, you could hear his deep, manly chuckle, even though the screen was still silent. As the English commentator Alistair Cooke marveled, "At a difficult period in American history, Douglas Fairbanks seemed to know all the answers."

Indeed, Fairbanks played a character so totally possessed by the sprit of action that he sometimes seemed less a man than an abstract kinetic force. So familiar were Americans with Fairbanks that to everyone who went to the movies from World War I to the advent of sound, he was simply "Doug." Born Douglas Ulman in 1883 to a prominent Jewish family in Denver, Doug changed his name to "Fairbanks" when he went on the stage, deftly Anglicizing himself into an assimilation many Jews were not otherwise permitted in a country which seethed with anti-Semitism. His stage persona was a rough draft of his screen character – feckless, lovable, a perpetual adolescent – but it was the movies that made Doug Doug. In a series of wildly popular modern dress action comedies between 1915 and 1920 with titles like He Comes Up Smiling, The Americano, A Modern Musketeer, and penultimately, His Majesty, the American, Fairbanks offered a breezy personality made up of qualities like dash, pluck, and especially pep, archaisms now, but terms much beloved in Doug’s prime. A cross-country wartime Liberty Bond tour with his fellow movie aristocrats, Charlie Chaplin and Mary Pickford, ignited the country’s affection for all three, and Doug’s marriage to Mary in 1920 sealed the compact. Doug and Mary’s lavish home in Hollywood, Pickfair, became a requisite stop for visiting royalty, and Doug and Mary themselves even took international goodwill junkets, greeted by gigantic crowds and obviously comfortable with their roles as ambassadors from dreamland.

Though Fairbanks was already serving as producer for his own films at Paramount, the leading studio of the day, he had even grander plans, of films made on gigantic budgets, of movies made from the world’s most thrilling stories and set in exotic climes… Doug wanted nothing less than to translate the distinctively modern American screen character he had patented into a worldwide figure, one who could vanquish foreign armies, Oriental tyrants, and medieval injustice with the same flamboyant grace with which he'd made Manhattan his kingdom in His Picture in the Papers in 1916. In the few short years since he'd burst like a whiz-bang on the American screen, Fairbanks’ scope had become international, and he sought nothing less than an exponential expansion of his screen character’s cultural reach. And so, with Mary Pickford, Charlie Chaplin, and director D.W. Griffith, he formed United Artists in 1919. The venture would give him complete control over the production and distribution of his films. It was the most remarkable financial arrangement any entertainer in American popular culture had ever attempted.

Fairbanks began by making three of the old style modern-dress comedies at United Artists. But the project that best announced Fairbanks’ global ambitions was 1920’s The Mark of Zorro. Based on a historical potboiler of a book called The Curse of Capistrano, the film, says Fairbanks’ biographer Richard Schickel, skillfully blended elements of the Western and the old Fairbanks roles in an effort to ease the transition to the new vision Fairbanks had in mind. Director Fred Niblo, skilled at action sequences, was enlisted to keep the plot moving as nimbly as Fairbanks. The film’s scenario writers used a very common device of the period: Zorro is a dual character, a romantic, avenging aristocrat by night, and a listless, worldweary fop by day. The Mark of Zorro alternates between light romance and thrills – more than 80 years on, Fairbanks’ stunts and physical exuberance continue to surprise audiences. The film is also an extended pun on sexual potency, for while the masked Zorro is a deadly swordsman, his cynical alter ego is, well, limp.

Fairbanks gauged his audience perfectly. The Mark of Zorro was a big hit, and he would never return to the old modern dress formula again. Even more spectacular action films followed, as Doug’s character roamed time and the world with cheery abandon. The Thief of Baghdad, Robin Hood, The Three Musketeers, The Black Pirate, and a sequel, Don Q., Son of Zorro – many were masterpieces of art direction, and each was beheld with rapture by Doug’s millions of fans. Like America, Doug had moved from being merely insouciant to colossal during the 1920’s.

Sound put Doug out of synch with himself. The slower, talkier films he was obliged to make didn't suit his unreflective, exuberant self. By 1929, and The Taming of the Shrew (with Mary) he suddenly seemed every bit his 46 years. With the Crash of 1929, his character’s boundless enthusiasm seemed worse than wrongheaded; perhaps just the sight of Doug reminded audiences of their own foolishness in ever believing that youthful irresponsibility could be a permanent state of being. The nation of Orpheums, Bijous, and Rialtos that once laughed and trembled with delight at Doug’s antics turned to grittier fare in the Depression, preferring gangsters and their golddigging dames to Doug’s acrobatic whimsy. Mary and Doug divorced after that, and Doug died young, in 1939, yet the news accounts of his passing make it seem as if he was a lonesome relic of a vanished epoch of unseemly fun. And so perhaps he was, but if anyone was responsible for making the `20’s merrier than they had a right to be, it was Douglas Fairbanks.

— Kevin Hagopian, Penn State University

For additional information, contact the Writers Institute at 518-442-5620 or online at https://www.albany.edu/writers-inst.

The Mark of Zorro

The Mark of Zorro