FILM NOTES

FILM NOTES INDEX

NYS WRITERS INSTITUTE

HOME PAGE

(Germany, 1999, 85 minutes, color, 35mm)

(In German with English subtitles)

Directed by Frieder Schlaich

Cast:

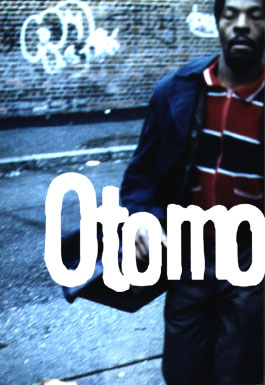

Isaach De Bankolé . . . . . . . . . . Otomo

Eva Mattes . . . . . . . . . . Gisela

Hanno Friedrich . . . . . . . . . .Heinz

Barnaby Metschurat . . . . . . . . . . Officer

At 6:14, on the morning of August 8, 1989, at a tram stop in Stuttgart, Germany, an impoverished Liberian and Cameroonian guest worker named Frederick Otomo took part in an angry confrontation with a transportation employee. Three hours later, on Stuttgart's Gainsburger Bridge, Otomo found himself surrounded by police, following a chase that aroused the entire city. Otomo is the fictionalized story of what happened in those hours.

When director Frieden Schlaich set out to investigate a story which had fascinated him since the day it occurred, he intended to make a documentary. But official sources were less than forthcoming about the affair, and dismayingly, so was the press. Schlaich felt that, having fanned the flames of hysteria about the guestworker "problem" during the 1980's, the press was less than anxious to revisit its moment of greatest ignominy. Turning to playwright Klaus Pohl, Schlaich elected to imagine the tortured last hours of Frederick Otomo.

Schlaich begins his film with Otomo waking and casting stones, doing push-ups -- and packing a bag with, among other things, some dirt from his homeland. He has been out of work for a long time, and is on his way to the state employment agency when his dispute with the subway clerk ignites a city against him. With casual fury, Stuttgart shuts him out; to everyone except an aging hippie and her granddaughter, Otomo is a pariah. In the hands of actor Isaach de Bankole (previously seen in the films of Jim Jarmusch), Frederick Otomo is a cryptic, inwardly focused soul, the vessel for the fears, the schemes, and only very occasionally, the hopes of the Stuttgarters who meet him on his brief, fevered transit between anonymity and notoriety.

The film's score, credited to Freudenkreis, undergirds Frederick Otomo's desperate flight across the city with eerie foreboding. We don't know exactly what will happen to Otomo, but we know that this film will not let him escape from the consequences of the disdain and hatred he has faced in his years in Germany.

The lessons the film brings proved too subtle for some to grasp. When the film opened at New York City's Film Forum, the New York Post spoke up fearlessly for xenophobia through its film reviewer, Jonathan Foreman, who sniffed "The filmmakers elect to make [Otomo] one of those silent, sullen fellows you often find in films of this find, who refuse to answer perfectly normal questions." The Post saw the problem the film presents not as racism, but as a surfeit of bureaucracy in Germany which "sentences refugees to misery by not allowing them to work." The American economy is also fed by our equivalent of guestworkers, immigrants, legal and illegal, who do the menial work from which native-born Americans recoil. Like Frederick Otomo, they suffer the profound insult of being thought of only in the mass, as "those silent, sullen fellows" whose Otherness can best be cured by "allowing them to work," rather than by treating them with economic and social dignity. Until then, the guestworkers will remain men and women "who refuse to answer perfectly normal questions" in a language they don't understand, because the questions are put to them by harassed officials and contemptuous citizens who see them as people without souls.

Perhaps it was not Frederick Otomo but The Post which was being silent and sullen. In 1999, in a New York City apartment house vestibule, police had fired 41 bullets at a Black man, an immigrant, Amadou Diallo, who did not understand why the men confronting him despised him, and who died because of that hatred. Like Diallo, Frederick Otomo was "known" by too many of his fellow citizens only as a crude stereotype in the media, and a silent, impassive man behind a broom.

— Kevin Hagopian, Penn State University

The following is taken from a review by Jessica Winter that appeared in The Village Voice, November 7, 2001:

Racial profiling has gone from municipal scourge to Justice Department imperative in the last couple months, and the events behind Otomo are a reminder of its lethal risks. On the morning of August 9, 1989, in Stuttgart, Germany, a Liberian refugee named Frederic Otomo scuffled with a ticket taker on a public train and ran from the scene; three hours later, stopped for questioning on the Gaisburger Bridge by several policemen, he brandished a bayonet knife, murdering two officers and injuring three others before he was shot to death by one of the felled men.

Director Frieder Schlaich has crafted a speculative semi-fiction around the incident—parallel stories that collide and combust. The film begins in the daybreak hours, when Otomo (Isaach de Bankolé) leaves his Spartan apartment to gather with an otherwise all-white motley crew of drunks and vagrants hoping to be chosen for day labor, only to leave empty-handed for lack of proper ID. Otomo then proceeds inexorably to the streetcar struggle, the deadly encounter on the bridge, and the three hours in between, during which two young officers (played by Barnaby Metschurat and Hanno Friedrich) search for their conspicuously black suspect. Otomo's actual whereabouts and activities during that time remain a mystery; Schlaich and co-screenwriter Klaus Pohl fill in the blanks with real-time swaths of Otomo's impotent wandering, the cops' close pursuit, and a wholly invented episode in which Otomo forges a brief, uneasy bond with a white woman, Gisela (frequent Fassbinder star Eva Mattes), who abets his flight.

As with Native Son, Otomo's free-fall trajectory implicitly grapples with the competing forces of environmental determinism and free will, presenting a central figure tyrannized by fear…. The early scenes—aided by Volker Tittel's dusky, blue-tinged cinematography—tersely establish Otomo's everyday life as a chilly labyrinth of gaping stares, snide condescension, and no-exit desperation. Otomo documents the institutionalized racism and xenophobia that painted one man into a corner, while never excusing the terrible means by which he took his final escape.

The following is taken from a review by Maria Garcia that appears on the website of Film Journal International:

The [Otomo incident], considered the worst crime in Stuttgart’s history, led to a bitter national debate in Germany, not unlike the one in New York City following the 1999 murder of West African Amadou Diallo. Germans were once again confronted with the spectre of institutionalized racism, as they questioned police procedures and deliberated over their country’s immigration policy.

Like many Germans, filmmaker Frieder Schlaich wasn’t satisfied with official explanations of the confrontation. Envisioning a documentary, he set out to research the crimes and reconstruct the events leading up to Otomo’s death. However, government agencies frustrated Schlaich’s efforts, and he found it impossible to gather enough information to make a film. In 1997, he went back to his research, and asked playwright Klaus Pohl to collaborate with him on a fictional recreation of the last hours of Otomo’s life….

Although Otomo is clearly intended for German audiences, the film nevertheless raises issues confronted by every Westernized nation. What moral and social obligations do the governments of these nations have toward the disenfranchised they agree to shelter? Otomo got asylum in Germany, but the filmmakers point to cultural attitudes, and entrenched legal, social and political obstacles which prevented the African from working at a job he liked, and one that would allow him to secure his economic independence.

While Schlaich depicts the discrimination Otomo (Isaach de Bankolé) suffers, what distinguishes the film is not its documentation of abuses. It is the filmmakers’ call for an admission of complicity on the part of Germans and, by extension, the citizens of all industrialized nations, for Otomo’s tragic life and the lives of others like him. Through this remarkable movie, Schlaich and Pohl make the case that there are no "random" acts of violence, that the confrontation between Otomo and the police was eight years in the making. Moral responsibility is a bitter pill, but Otomo argues that without it, no one will ever dismantle state-sanctioned injustices.

The following is taken from a New York Times review by Elvis Mitchell that appeared Nov. 7, 2001:

The German social melodrama ''Otomo'' has a fascinating weight. Spare and taut, it follows the story of Frederic Otomo, a Cameroon immigrant living in Stuttgart. He's played by Isaach de Bankolé, whose fine bone structure and faraway gaze make him seem even further apart from the pale, suspicious Germans he lives among. He seems to be staring into the distance when he's in the same room with someone, an aloofness that plays as a kind of distracted royalty….

''Otomo'' begins to feel like a new brand of social melodrama: ''I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang,'' as directed by Oliver Stone. The punch doesn't offer the cliché of relief we're used to; instead, it seals Otomo's fate. With nowhere to go, he runs the streets, given to paroxysms of frustration. In one powerful moment he throws an anguished fit while framed at the end of a tunnel. Mr. Schlaich stages this moment pitilessly; his subject is an ant caught in a helpless rage that is both justified and insignificant.

Mr. Schlaich has shot the movie in unflattering terms; it's lighted like a bathroom mirror, and the harshness fits the storytelling. He and his co-writer, Klaus Pohl, slip in irony early on: when we're introduced to Heinz (Hanno Friedrich) and Rolf (Barnaby Metschurat), the cops who end up on the case, the aspiring songwriter Rolf is rapping a lame pop lyric that he hopes will catapult him out of his daily routine. A couple of scenes later, Rolf utters his unconscious racism. ''What's up with him?'' he asks of a guy loitering on the streets.

''Nothing -- he's black,'' says the blond and militantly decent Heinz, rolling his eyes.

The plot line with Heinz and Rolf is too obvious for what the director is trying to accomplish. Heinz is a promotion away from starting a family, and Rolf dreams of ending his on-the-job monotony. This state is about to end, but not in the way he expects….

As Mr. de Bankolé plays Otomo, his bearing puts people off; he's unpleasant. And the mistreatment he suffers has to be responsible for his demeanor: he's always peering out of the corners of his eyes. But the movie sets up the possibility that he may have always been hard to know.

Mr. de Bankolé's mouth is often drawn into a slim, angry line, as he tolerates the constant barrage of insults. It's a far different performance from the one he gave as the vivacious rooftop philosopher in ''Ghost Dog'' last year. In that film each line floated out, a happy thought wafting toward heaven. Here he looks like a man who is guarded, cut off from the world because of the blunt racism he's subjected to….

The director's cold-blooded minimalism is abetted by the chilled electronica groove of the score by Freundeskreis. It helps to establish the mood of the piece and gradually becomes its pulse as the manhunt for Otomo goes on. ''Otomo'' is a bleak and powerful work, one we probably need more than ever these days.

For additional information, contact the Writers Institute at 518-442-5620 or online at https://www.albany.edu/writers-inst.

Otomo

Otomo