FILM NOTES

FILM NOTES INDEX

NYS WRITERS INSTITUTE

HOME PAGE

On the Waterfront

On the Waterfront

(United States, 1954, 108 minutes, b&w, 35mm)

Directed by Elia Kazan

Based on a screenplay by Budd Schulberg

Starring:

Marlon Brando . . . . . . . . . . Terry Malloy

Karl Malden . . . . . . . . . . Father Barry

Lee J. Cobb . . . . . . . . . . Johnny Friendly

Rod Steiger . . . . . . . . . . Charley 'the Gent' Malloy

Eva Marie Saint . . . . . . . . . . Edie Doyle

The

following film notes were prepared for the New York State Writers

Institute by Kevin Jack Hagopian, Senior Lecturer in Media Studies

at Pennsylvania State University:

It is one of the most justly famous scenes in the history of the American cinema, and surely one of the simplest: two brothers, talking in the back seat of a cab. Once they were joined by the hope of climbing out of their slum childhood through the patronage of "important people." Now they are divided by the emerging moral sense of one of the brothers, and the rising fear of the other that the important people may turn on them both and rend them.

It is of course, Elia Kazan's On The Waterfront, a film whose themes of brotherly loyalty and political betrayal have become so integral to the American film that another brilliant film, 1980's Raging Bull, is so unashamedly inspired by it that the protagonist of the latter film recites the indelible lines of the taxicab scene.

The stories of the making of On the Waterfront are legion. That the film was originally a scenario written by Arthur Miller, who fell out with director Elia Kazan over Kazan's political choices, and whose own research on waterfront crime would later see light as the distinguished play A View From the Bridge. That the project was originally to star Hoboken's most famous son, Frank Sinatra. That filming was facilitated with the aid of the same New York mobsters who had poisoned the longshoreman's union. Even the remembrances of the makers of the film have passed into film folklore, told and retold like war stories: actor Rod Steiger recalled having to read his lines in the cab to a listless assistant director, Marlon Brando having left the set to see his therapist. (And everyone holding their breath, hoping none of us would ask what venetian blinds were doing on the back window of a taxi. We never did.) Eva Marie Saint's dropped glove, in the playground scene, turning a botched take into a lyrical moment when Brando picks it up, and pulls it on over his own outsized fighter's hand. (And that, too, might have been more planning that inspiration.)

Then too, there is the controversy: On the Waterfront is its feisty writer and angry director's very public articulation of their need to dissociate themselves with their former political and cultural allies, loudly, forcefully, and forever. The story of a rat with honor, On the Waterfront's own reception has been less that of a film than of an iconoclastic political essay which seems to infuriate everyone who reads it. Humane yet bitter, raging yet reflective, On the Waterfront contains multitudes.

No other American film links together so many beautifully structured sequences, each its own tiny movie. Take a close look at our introduction to the ethics of the waterfront in an early sequence in Johnny Friendly's bar, after Terry has reluctantly induced a stool pigeon to his death. Kazan's theatrical background staging the works of Williams and Miller is in evidence here, the closed world of the Friendly bar made tense and real through Kazan's blocking choices, and the minute pieces of business he gives every character. A dozen minor characters crowd the backroom at Friendly's, some even without lines, but each perfectly drawn, and each a creature of the backslapping world of mutual obligations Johnny Friendly and his crew have set up. We find out here that the waterfront is a debtor's hell, and every longshoreman owes Johnny something -- a job, money, even his soul. Here we meet Terry Malloy and his brother Charley, and here we find out concisely what each of them owe to Johnny. The story of the movie is the choice each brother faces in how they will work off their indebtedness, in blood or testimony.

No other American film links together so many beautifully structured sequences, each its own tiny movie. Take a close look at our introduction to the ethics of the waterfront in an early sequence in Johnny Friendly's bar, after Terry has reluctantly induced a stool pigeon to his death. Kazan's theatrical background staging the works of Williams and Miller is in evidence here, the closed world of the Friendly bar made tense and real through Kazan's blocking choices, and the minute pieces of business he gives every character. A dozen minor characters crowd the backroom at Friendly's, some even without lines, but each perfectly drawn, and each a creature of the backslapping world of mutual obligations Johnny Friendly and his crew have set up. We find out here that the waterfront is a debtor's hell, and every longshoreman owes Johnny something -- a job, money, even his soul. Here we meet Terry Malloy and his brother Charley, and here we find out concisely what each of them owe to Johnny. The story of the movie is the choice each brother faces in how they will work off their indebtedness, in blood or testimony.

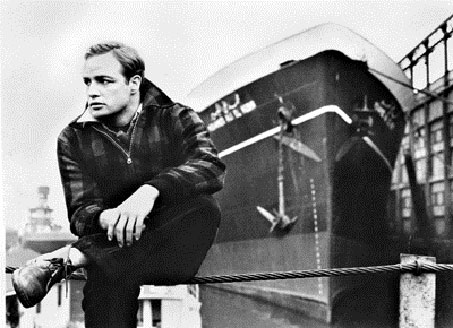

The look and feel of On the Waterfront is gloomy, ascetic, and entirely plausible, an implicit rejection by Kazan of the earnest but blandly sentimental Hollywood films he had made in the previous decade, like Gentleman's Agreement and A Tree Grows in Brooklyn. The gritty photography by Boris Kaufman and the extensive New Jersey location shooting make On the Waterfront a legitimate bearer of the European neorealist traditions so many other American films of the time (like Jules Dassin's Naked City, or Fred Zinnemann's Theresa) started to imitate, but couldn't, falling off in later reels into Hollywood convention. Kazan sustains the proletarian angst of the docks through every shot and every space of the film. You see it in the chill breath of the actors in the freezing, gray New Jersey afternoons, and you feel it in the sweaty Polish tavern wedding scene, where the people of the waterfront seek release from their toil with such frantic energy.

Kazan, not himself particularly religious, understands the power of religious imagery. There are the job tokens, like Roman coins, scattered among the desperate souls at the shape-up. There is the film's betrayal plot, ingeniously inverted from its biblical model to make betrayal a saintly act. And there is, famously, Terry's martyrdom and redemption, the long walk back from his dockside Calvary. If Karl Malden's Father Barry sometimes rings a sanctimonious note into Terry's story, it is because the moral analysis of the film makes his talk of religious parallels unnecessary: the philosophical job of On the Waterfront, to show that the life of an ordinary working stiff can become a thing with transcendent moral implications, is accomplished without his hard-nosed pieties.

And finally, there are the politics of On the Waterfront. Before the making of On the Waterfront, Kazan, like others in the movies, had renounced his youthful Left politics under pressure from a Congressional kangaroo court, the House Committee on Unamerican Activities. In the years after their awkward, stage-managed testimony, many had made it clear they had testified to save their careers, and some of these found grudging reacceptance among their peers in the business.

But Kazan testified with defiance, rejecting the idealistic communitarian politics of his past with a vengeance that spoke as much of self-loathing as political recantation. Not content with this public ritual, Kazan took out an ad in the New York Times "explaining" his actions, and urging others to join him. It was a trademark gesture: Kazan always insisted on the rightness of his beliefs and methods, not only for him, but for everyone. On the Waterfront benefits greatly from this righteousness, this sturdiness of belief. With Budd Schulberg's literate and well-constructed screenplay as a blueprint, and Marlon Brando's empathetic performance as Terry Malloy to light his way, Kazan's commitment in this film to a course of absolute individualism is as unwavering as it is, I believe, self-destructive.

Many years ago, noted director Lindsay Anderson, then a film critic, wrote an essay he called simply, "The Last Sequence of On the Waterfront." In it, he scored the politics of the film's last moments. And yet, as a filmmaker to be, he recognized Kazan's extraordinary ability to convince us, through the cinematic languages of editing, camerawork, and performance, of the rightness of Terry's actions. Therein, said, Anderson, lay the danger. Others of us, in accord with Anderson's politics, might say that proof of the political power of art is most in evidence when it can bring us, even against our initial will and for only a moment, to a place of questioning the old verities. Even the most treasured old truths must be strong enough to stand up against an attack as biting and incisive as On the Waterfront.

Kazan never warmed to those professional anti-Communists who thought he was agreeing with them, recognizing them mostly as opportunists or fools. He would be no one's spokesman but his own. And yet, his modern masterwork of rugged individualism continued to testify for him, angering those on the Left like Anderson as much for its hard-won artistic power to persuade as for its basic politics. In his last years, when Kazan was given a long-disputed honorary Academy Award, he was escorted onstage by Martin Scorcese and Robert DeNiro, two masters of American screen realism whose lifework had been inspired by Kazan, and by this film in particular. It was thought that the presence of Scorcese and DeNiro would forestall demonstrations from the audience, much the way the accompaniment of Johnny Friendly by his gigantic bodyguards, Truck and Tillio, had generated respect on the docks in On the Waterfront. But Kazan did not need the muscle. Frail, the once-fiery personality now sunken behind elderly eyes, Kazan watched the surprisingly passionate response of the audience when he came on stage with what appeared to be a measure of satisfaction. He seemed to recognize that his outspokenness would outlive him. He was right.

— Kevin Hagopian, Penn State University

For additional information, contact the Writers Institute at 518-442-5620 or online at https://www.albany.edu/writers-inst.