FILM NOTES

FILM NOTES INDEX

NYS WRITERS INSTITUTE

HOME PAGE

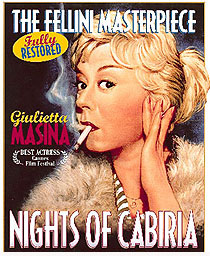

Directed by Federico Fellini

(Italy, 1957, 117 minutes, b&w, 35mm, in Italian w/English subtitles)

Starring:

Guilietta Masina . . . . . . . . . .Maria "Cabiria" Ceccarelli

François Périer . . . . . . . . . . Oscar D'Onofrio

Franca Marzi . . . . . . . . . . Wanda

Dorian Gray . . . . . . . . . . Jessy

Aldo Silvani . . . . . . . . . . Il mago

The

following film notes were prepared for the New York State Writers

Institute by Kevin Jack Hagopian, Senior Lecturer in Media Studies

at Pennsylvania State University:

In 1942, the 22 year-old actress Giulietta Masina met a ne'er do well student who had enrolled in the University of Rome's law school to avoid being drafted into Mussolini's Italian Army, but who seldom attended classes. Instead, he preferred to spend his time as a satirical cartoonist and amateur radio writer. Passionate and dreamy, Federico Fellini appealed to the ethereal and intelligent Masina, and Masina achieved a personal success in a radio play written by Fellini. Their long association would magnify each of them: Masina's delicate gift for comedy found its perfect setting in Fellini's surreal but humane tales of existential wanderers in the fields of memory and longing, and Masina would find Fellini's directorial touch loving and subtle. Collaborators in life as well as art, the Masina-Fellini screen relationship joins only a few others in its significance and sustained quality. Only the partnerships of Liv Ullman and Ingmar Bergman, D.W. Griffith and Lillian Gish, Chaplin and Edna Purviance, and Zhang Yimou and Gong Li have equaled that between Federico Fellini and Giulietta Masina. Together, they made Variety Lights (1951), The White Sheik (1952), La Strada (1954), Il Bidone (1955), Juliet of the Spirits (1965), and Ginger and Fred (1986), and the oeuvre of Federico Fellini would be unimaginable without Giulietta Masina's graceful comedy and endearing, tiny face.

They married in 1943, and Masina quickly established herself in film and theater. Indeed, she was much the better-known of the two during Fellini's apprenticeship in the Italian film industry after the war. Nights of Cabiria was their fifth film together, and stands among the finest work they produced.

Masina's Cabiria is a prostitute, and the film begins with a petty street crime; her purse is stolen, and she is thrown into the Tiber. The grimy waters of the Tiber work a deep change on Cabiria. Her nights start to become ones of transcendence and redemption in one of the cinema's most remarkable stories of spiritual transformation. Her near-drowning forces Cabiria to reconsider her life, and her question, "What if I had died?" is the beginning of a quest for meaning in a life that seems initially to lack moral justification. But Fellini does not have to moralize against the sordid exchange of sex for money, for his protean sensibility acknowledges the truth of all existence, and the dignity possible in almost all ways of life.

Fellini's previous film had not been successful, and Nights of Cabiria took a skein of eleven producers to get to the screen. But Masina's performance, among the most varied and complex in her career, was a revelation. Perhaps as close to a female Chaplin as we will ever see, Masina's Cabiria is capable of delicate slapstick and intense pathos; the scenes of her trying to compete with the high class whores of the Via Veneto seem inspired by the Chaplin of City Lights. Cabiria meets a movie star, the object of her veneration, and he is immediately made a stand-in for one of Fellini's most characteristic themes: the director's paradoxical love for Church ritual and simultaneous ridicule of religious hypocrisy. Later, at the Lux theater, Cabiria will surrender herself to the fantastic realms of imagination signified by the stage in so much of Fellini's work. But her near-death experience has not, strictly speaking, transformed Cabiria; it is she who chooses to transform herself, using the opportunities at hand. Hers is an outside-in metamorphosis, using the ordinary events and coincidences of life to create a luminous new self. Masina makes this shift miraculous. Her face grows softer, and even appears to shine. Her gaze at the camera in the second half of the film is profoundly disconcerting. We feel as if she is addressing us, mutely, her quizzical smile asking us about our own potential for change and liberation from the tyranny of convention and hypocrisy.

Fellini claimed that his films "don't have what is called a final scene." He believed the conclusion was the audience's to write, not his: "My films give the audience a very exact responsibility. For instance, they must decide what Cabiria's end is going to be. Her fate is in the hands of each one of us. If the film has moved us, and troubled us, we must immediately begin to have new relationships with our neighbors. This must start the first time we meet our friends or our wife, since anyone may be a Cabiria."

— Kevin Hagopian, Penn State University

For additional information, contact the Writers Institute at 518-442-5620 or online at https://www.albany.edu/writers-inst.

Nights of Cabiria

Nights of Cabiria