FILM NOTES

FILM NOTES INDEX

NYS WRITERS INSTITUTE

HOME PAGE

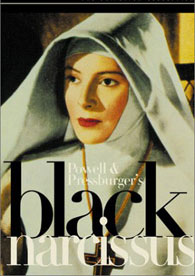

Black Narcissus

Black Narcissus

Directed by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger

(United Kingdom, 1947, 100 minutes, color, 35mm)

Cast:

Deborah Kerr . . . . . . . . . . Sister Clodagh

Flora Robson . . . . . . . . . . Sister Philippa

Kathleen Byron. . . . . . . . . . Sister Ruth

The

following film notes were prepared for the New York State Writers

Institute by Kevin Jack Hagopian, Senior Lecturer in Media Studies

at Pennsylvania State University:

It had been a black and white war in England. The Blitz had brought devastation to London and Portsmouth and Coventry and a dozen other major cities, leaving rubble that would take a decade to clear away and rebuild. The U-boat offensive had nearly strangled the country, reducing the average Briton's diet to something like prison fare; rationing of some commodities continued for years. And the effort of arming and provisioning a far-flung navy, army, and air force had drained the island nation of anything like luxuries -- let alone new clothes and automobiles. And there were the dead -- 244,000 British soldiers, and 60,000 civilians. Peace dawned gray and tired in England.

Into this monochromatic and weary culture came the Technicolor films of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger's remarkable production company, The Archers. Their work must have seemed like a perverse and delightful rainbow in that age of austerity. Beginning in wartime with films such as The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, and extending to 1953's international success The Red Shoes, The Archers brought a world of exoticism and intoxicating sexuality to Britain's screens, in a sustained flourish of cinematic colour which has never been equaled. They clearly influenced the great American postwar masters of expressive color, Vincente Minnelli and Douglas Sirk, and directors of the next generation like Martin Scorcese point to The Archers as an inspiration for their own commitment to the fantastic possibilities of color in the cinema. Films like Scorcese's New York, New York and Francis Coppola's One from the Heart are personal valentines to the spirit of The Archers.

Among The Archers' color masterworks (Blimp, The Red Shoes, Tales of Hoffman, A Matter of Life and Death) 1947's Black Narcissus stands out for its portrait of mad passions rendered in a palette that must have seemed almost unbearably intense in 1947. The film is based on Rumer Godden's 1939 novel about a group of nuns who find themselves the unwilling tenants of a Himalayan castle-turned-convent, clinic, and school. "Castle" is a euphemism, for the structure was once the home of a warlord's concubines, and its profane heritage seems to infuse the nuns' domicilage there with an unrepressible, even eerie eroticism. Sister Clodagh (Deborah Kerr, in perhaps her finest role) attempts to tame both her charges (the local population) and her fellow nuns. The children of her school, including an exquisite young prince (Sabu, in the crowning moment of his career), attend smilingly to their lessons, but without noticeable interest in exchanging their expansively earthy customs for the constrictions of Catholic guilt.

The nuns, however, are in trouble from the first. It is a cold wind that blows through the ambitiously-named St. Faith's, clinging to the sheer walls of an angular mountain, but it brings with it the heat of jealousy and romance. Sister Philippa's (Flora Robson) garden is overrun with resplendent, "useless" flowers, crowding out her practical crop of vegetables. The nuns' medical ministrations can't prevent the death of an infant. Soon, the colony is divided against itself, as Sister Clodagh and Sister Ruth (Kathleen Byron) compete for the attentions of the local British agent, Mr. Dean (David Farrar) a professional cynic who has gone happily native. Sister Ruth's passions overflow their fragile vessel, and her slow and subtle derangement is among the great performances of madness ever put on the screen.

Powell and Pressburger passed up the opportunity to film on location. Instead, they turned to two masters of illusion, art director Alfred Junge and cinematographer Jack Cardiff, to invent an Orientalist landscape as timeless and placeless as that of The Wizard of Oz' Emerald City or Lost Horizon's Shangri-La. The results are beyond description. The rocky fastnesses and overblooming gardens of the film, rendered in the super-saturated hues of true Technicolor, give the film a sensual and otherworldly quality. And yet, not a foot of film was shot outside of England, something a first-time viewer of the film finds almost impossible to credit. (Even the "Indian gardens" of the film were found on a Sussex estate called Leonardslee Gardens; England's moist, mild climate turned out to make suitable soil for many tropical plants.) Junge built the film's gigantic House of Women/St. Faith's set on the backlot of Pinewood Studios, and through his artistry with matte paintings and Cardiff's skillful cinematography, transport us to a nameless valley high in the Himalayas. Cardiff's facility with the huge, 600-pound Technicolor camera still astonishes modern cameramen and women who see the film. Three-strip Technicolor required that sets be virtually flooded with light, yet Cardiff paints St. Faith as a place of real as well as moral shadows, a gloomy cloister of lust and envy. His touch with color is as delicate as it is emphatic; the film's most daring sequence is resolved by the carmine red of a woman's lipstick, and the moment is tragically unforgettable.

In later years, Powell second-guessed his decision not to film on location; shooting in India, he thought, would have made Black Narcissus more realistic. But who would have wanted it that way? What began as a portrait of an exotic land and its people became an exotic thing in itself, a hothouse creation inconceivable without the resources of a big studio and its gifted magician/craftspeople. Said Powell, "In Black Narcissus, I started out almost as a documentary director and ended up as a producer of opera."

— Kevin Hagopian, Penn State University

For additional information, contact the Writers Institute at 518-442-5620 or online at https://www.albany.edu/writers-inst.