FILM NOTES

FILM NOTES INDEX

NYS WRITERS INSTITUTE

HOME PAGE

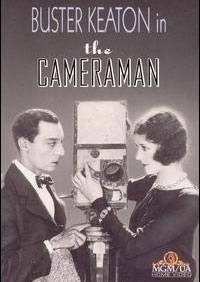

Directed by Edward Sedgwick and Buster Keaton (uncredited)

(United States, 1928, 75 minutes, b&w and color, 35mm)

Silent with piano accompaniment

Cast:

Buster Keaton. . . . . . . . . . Buster

Marceline Day . . . . . . . . . .Sally Richards

Harold Goodwin . . . . . . . . . .Harold Stagg

The

following film notes were prepared for the New York State Writers

Institute by Kevin Jack Hagopian, Senior Lecturer in Media Studies

at Pennsylvania State University:

In the spring of 1928, Buster Keaton was making perhaps the most perfectly engineered films in the history of the American cinema. His films were organized around linked gags in a structure developed by a rotating team of a half-dozen or so of Keaton's cronies from vaudeville and from the days of Keaton's own long apprenticeship in two-reelers, the short cinema form that from 1917 to 1923 had allowed him to hone his comic craft into a laugh-getting machine that was still deeply humane and compassionate, oiled by human kindness and romance. When Keaton, Eddie Kline, Joe Mitchell, Clyde Bruckman, and the rest of the gang hit a snag, they simply left the set and indulged in Buster Keaton's other great passion: the Keaton unit played baseball until someone figured out how to get Buster out of the plot corner they had just painted him into. At United Artists, producer Joseph Schenck did more than let the inimitable Keaton have his head: he let Keaton have his own studio. Fortunately, Keaton's creative team was joined at the pocketbook, as well as the hip; Schenck kept them all under contract between pictures to dream up the vast landscape of interlocking sight gags, prop jokes, pratfalls, and character bits that made the Keaton films popular in their day, and brilliant in ours; seen today, the United Artists Keaton features -- Sherlock Jr., The Navigator, Seven Chances, and the penultimate The General -- are masterpieces of comic invention, serial jokes borne in the fevered imaginations of Keaton and his crew, and then incubated in the cloistered madness of Keaton's United Artists' principality. United Artists was then still "The Studio Owned by the Stars," designed by Mark Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks, and Charlie Chaplin to be both a financial boon and a creative haven for film artists, the company actually an archipelago of truly independent producers. For Keaton, it was paradise.

But in 1928, after releasing the brilliant Steamboat Bill, Jr., Keaton was talked into dismantling the financial structure of his studio, and coming under the aegis of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. The massive hyphenate was already, in only its fourth year of existence, a huge picture-making operation that had made a shotgun marriage of art and commerce signified by the paradoxical phrase "studio system." Keaton stood to make a great deal more money under the arrangement with MGM. He needed the dough. Unable to refuse anybody anything, fame had brought the gentle, financially illiterate Keaton a gaggle of glad-handing "friends," and in-laws who behaved more like outlaws. Keaton was saddled with one of the most palatial homes in the movie colony (the absurdly titled "Italian Villa" had two dozen or more rooms, some of which Keaton claimed never to have seen) filled with hangers-on, each of them with his hand out.

So Keaton went to MGM: many years later, he called it, "the worst mistake of my career." His traveling Lambs Club of comic writers went with him, but was scattered across the MGM lot, working on films for everyone except Keaton. As a result, the gag structures of his MGM films feel truncated and unfinished as a result. Meanwhile, in pursuit of economy and the kind of films it liked to call "product," the MGM suits harassed Keaton into economies and "sure-fire" plots that failed to combust. Keaton would stay at MGM through 1933; he would stay through the coming of sound, he would stay through increasingly witless scenarios and scripts, he would stay through a mismatched series of films with another MGM "property," Jimmy Durante, that turned Keaton into a grumpy second banana in his own films. He would stay at MGM so long that frustration and divorce and bankruptcy and alcoholism almost killed him. When he left, virtually thrown off the lot, it was for ignominious St. Helena of Poverty Row short films, clunky one-off "vehicles" shot overseas, and pathetic cameos.

But it wasn't all over just yet. At MGM, Keaton had one more great film left in him. In the fall of 1928, his unit was still intact, and together they made The Cameraman. It is a film that shows off the trademark organic Keaton gags, each one developing and coming to fruition over several minutes of screen time. Here, Buster is cast as an aspiring, but lousy, newsreel cameraman, in quest of the perfect shot and of course, the requisite pretty but oblivious Keaton ingenue. Buster keeps missing the great shot, but we never do: the Tong War, the Yankee Stadium solitary baseball routine, the Coney Island sequence, are all vintage Keaton. And the upstairs-downstairs joke is a piece of romantic comic business that is among the highlights of the American cinema; assured, balletic in its framing and mise-en-scene, and of such perfect logic that it fully deserves that greatest honorific adjective of screen comedy, "Keatonesque."

My own favorite routine in the film is the business with the fire engine; with its modernist multiple exposures and scenes of constant urban confusion and mayhem circulating around Buster's clinically observant camera lens, more than any of his films, The Cameraman makes the case for Buster as one of the century's great surrealists. (In the year of The Cameraman's release, Luis Bunuel and Salvador Dali would pay homage to Keaton in their brilliant surrealist fantasy, Un Chien Andalou.)

Just before burning out, the filament of a light bulb will often flare brightly. So it is in The Cameraman, where Buster Keaton's mad dash for that fire engine seems in retrospect like a man running for his life, putting every calorie of energy into what might be his last steps.

— Kevin Hagopian, Penn State University

For additional information, contact the Writers Institute at 518-442-5620 or online at https://www.albany.edu/writers-inst.

The Cameraman

The Cameraman