FILM NOTES

FILM NOTES INDEX

NYS WRITERS INSTITUTE

HOME PAGE

Directed by Joseph L. Mankiewicz

(United States, 1949, 103 minutes, b&w, 35mm)

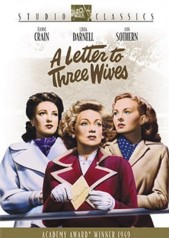

Cast:

Jeanne Crain . . . . . . . . . . Deborah Bishop

Linda Darnell . . . . . . . . . . Lora Mae Hollingsway

Ann Sothern . . . . . . . . . . Rita Phipps

Kirk Douglas . . . . . . . . . George Phipps

Paul Douglas . . . . . . . . . Porter Hollingsway

Jeffrey Lynn . . . . . . . . . Brad Bishop

The

following film notes were prepared for the New York State Writers

Institute by Kevin Jack Hagopian, Senior Lecturer in Media Studies

at Pennsylvania State University:

In the late 1940's and early 1950's, the American cinematic comedy of manners saw a brief Indian summer. Made possible by the studio system operating at high tide and with writers and directors nurtured in the theater and now, after decades in the sound cinema, experienced enough in the ways of film to craft a truly mature genre, directors like George Cukor, working with gifted writers like Garson Kanin and Ruth Gordon, and Joseph Mankiewicz, who directed his own scripts, the American cinema wryly commented on postwar American prosperity, the returning veteran, and the shifting landscapes of gender roles. With their ensemble casts frequently playing comic encounters in long takes and in medium shots, films like Cukor's Adam's Rib, Born Yesterday, and It Should Happen to You were "theatrical," in the very best sense, finding both joy and social criticism in the ways men and women played roles with one another, and even with themselves, in their everyday lives. Other films, such as H.C. Potter's Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House, and Walter Lang's Sitting Pretty, satirized suburbanization and "progressive" child-rearing; in their own way, the postwar comedy of manners constitutes a generous but insistent critique of the American dream, circa 1949.

Writer-director-producer Joseph Mankiewicz' contributions to this cycle were perhaps small in number, but immense in influence. A Letter to Three Wives remains one of the choicest, the wittiest, of all American social comedies before Annie Hall.

A Letter to Three Wives is an omnibus film, its three stories ingeniously interlocked through meetings among the characters, flashbacks, and the voice-over of an unseen romantic catalyst, the town siren, Addie Ross (Addie's purring, sultry voice is that of Celeste Holm). There are Rita and George Phipps, played by Kirk Douglas and Anne Southern, he a high school teacher, bitter at being taken for granted by society, she a writer of wretched radio dramas, frustrated at George's broken-record denunciation of Philistinism -- even if the Philistines are paying their mortgage and happen to be in the room at the time. The Phipps' are friends with the Bishops, Deborah and Brad, played by Jeanne Crain and Jeffrey Lynn, who fell in love during their military service in World War II (she'd been in the WAVEs); winning the peace on the home front turns out to be more complicated for the Bishops than winning the war. The Phipps and the Bishops are all friends with the film's most outlandish and endearing couple, Porter Hollingsway, played by lumpen-good guy Paul Douglas, and his wife, the former Lora Mae Finney, a hard-boiled bombshell from (literally) across the tracks, played unforgettably by Twentieth Century-Fox's resident hard-boiled bombshell, Linda Darnell. At one point, a friend suggests that Lora Mae's somewhat dowdy dress might be improved by "addin' some beads." "What I got don't need beads," scoffs the dauntingly voluptuous Lora Mae; truer words have never been spoken. Lora Mae and Porter's marriage, unlike the Phipps' and the Bishops, is based, not on love, but a contract: Lora Mae gets a life furnished by Porter's appliance store nouveau wealth, and Porter gets, well, Lora Mae. The three couples settle down in their suburban New York town to quietly strive against one another. Over the years, their individual anxieties have begun to torque each of the marriages to the limits of patience.

Now, a letter arrives... One of the three families will be destroyed, because the invisible Addie has decreed it to be so. But which will it be? The Phipps' class-conscious union? The Bishops' wartime romance? The Hollingsways' contract marriage?

A Letter to Three Wives began life as a property to be made by the master of the comedy of manners, Ernst Lubitsch, but Lubitsch's death in 1947, and problems with engineering the three stories into a coherent whole shelved the project; the story on which the film was based had five wives. (Indeed, the film's photo-finish conclusion is still confusing enough that one of the film's viewers, General Douglas MacArthur, then in Tokyo in charge of the Occupation of Japan, had an aide write to Mankiewicz asking who Addie Ross had actually run off with.) A Letter to Three Wives is unjustly known today as Mankiewicz's rehearsal for the now more well-known All About Eve the following year. In fact, A Letter to Three Wives was a surprise hit, and won for Mankiewicz his first two Oscars, for directing and writing. It is a hearty and intelligent comedy, tweaking hypocrisy at the same moment that it clearly yearns for reconciliation within and between its three couples. A Letter to Three Wives has a marvelous added attraction: this was bristly comedienne Thelma Ritter's first major film, and she runs all the way to Flatbush with every scene she's in. And for all the talk, so beloved of the urbane Mankiewicz, there is the unforced laughter of the film's several moments of physical comedy; if there's a funnier quick visual gag than the train bit in the American cinema, then I'm going looking for it.

"We all have a lot of the past in our presents," punned Mankiewicz about his frequent use of flashbacks, but he could as well have been thinking about the way the years since 1939 have weighed on these three sets of characters, and what a struggle it is for them to escape the security they all thought they wanted...

— Kevin Hagopian, Penn State University

For additional information, contact the Writers Institute at 518-442-5620 or online at https://www.albany.edu/writers-inst.

A Letter to Three Wives

A Letter to Three Wives