FILM NOTES

FILM NOTES INDEX

NYS WRITERS INSTITUTE

HOME PAGE

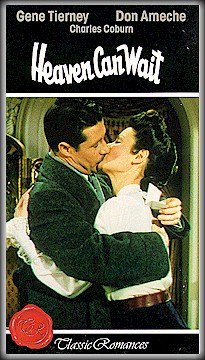

Heaven Can Wait

Heaven Can Wait

(American, 1943, 112 minutes, color, 35 mm)

Directed by Ernst Lubitsch

Cast:

Gene Tierney . . . . . . . . . . Martha

Don Ameche . . . . . . . . . . Henry Van Cleve

Charles Coburn . . . . . . . . . . Hugo Van Cleve

Marjorie Main . . . . . . . . . . Mrs. Strabel

Henry: "Oh, no, no--not in the least. I had finished my dinner--"

Excellency: "A good one, I hope."

Henry: "Excellent--I ate everything the doctor forbade. And then -- well to make a long story short, shall we say I fell asleep without realizing it. And when I awakened, there were my relatives, speaking in low tones, saying nothing but the kindest things about me. Then I knew I was dead."

Excellency: "And your funeral--was it satisfactory?"

Henry: "Well, there was a lot of crying, so I believe everybody had a good time."

Few of us get to write our own epitaph. HEAVEN CAN WAIT masquerades lightly as the beyond-the-grave recollections of the aged roué Henry Van Cleve, but the film is in fact Ernst Lubitsch's own death foretold, his own life summed up.

"The Lubitsch touch" included equal measures of Continental suavity, a studiously blasé attitude toward sex, and a chortling skepticism about any allegedly high-flown human motives. By 1943, Lubitsch's screenplays and directing assignments had institutionalized this delightful bouillabaisse. In such films as TROUBLE IN PARADISE (1932), DESIGN FOR LIVING (1933), and NINOTCHKA (1939), the German emigré had punctured American self-importance with a Viennese-styled needle of exquisite sharpness. His films were delightful confections of sex and sentiment, affectionate burlesques of his host country's preoccupations with appearances-at-all-costs, films that still somehow never lost their good nature. He'd been at it so long (he'd made his first film back in Germany, in 1915), it seemed as if he must go on forever.

But a dour mortality was finally staring back at him. It was wartime, and Lubitsch despaired over a Europe in flames. His heart was failing, partially the fault of the gigantic cigars he chain-smoked, partially (his friends believed) the result of his long good fight against studio tyranny and hypocrisy. He realized, he told Samson Raphaelson, his friend and collaborator on nine films including HEAVEN CAN WAIT, that he had made many films about Americans, but none about America, a place he loved even more dearly for all its peccadilloes and false prudery. As the two set about to make Lubitsch's first film in color, Lubitsch suffered a series of heart attacks. Raphaelson was told that Lubitsch could not survive, and so began composing a eulogy. As he dictated, his hardboiled secretary wept. As Raphaelson contemplated the homely German in the ill-fitting clothes whose lacework wit had transformed Hollywood from a provincial town on the edge of a desert into a (at least occasionally) civilized and creative place, the phrases poured like Rhine wine:

"I never saw, even in this territory of egotists, anyone who didn't light up with pleasure in Lubitsch's company. We got that pleasure, not from his brilliancy or his rightness. . . but from the purity and childlike delight of his lifelong love affair with ideas. . . He had no time for manners, but the grace within him was unmistakable, and everyone kindled to it, errand boy and mogul, mechanic and artist. Garbo smiled, indeed, in his presence, and so did Sinclair Lewis and Thomas Mann. He was born with the happy gift of revealing himself instantly to all."

But Lubitsch survived to shoot HEAVEN CAN WAIT, and Raphaelson happily put away his tribute, swearing his secretary to secrecy about his flood of sentiment. For Lubitsch, the film that resulted from this dire period is surely one of his most lovely, an unassuming, casual announcement that death held no fear for him. The amiable, emphatically American Don Ameche as Henry van Cleve stands in for Lubitsch quite nicely, and the ridiculous world over which he presides is a fantasy of provincialism outraged (the preposterous Mr. and Mrs. Strabel, nouveau boors just in from, hopelessly, Kansas), and European sexual matter-of-factness (the worldly Mademoiselle, every adolescent boy's French maid). In Lubitsch's version of the afterlife, everyone is as civilized and expansive as he is; even the devil (His Excellency), as played by Laird Cregar, is a patient sophisticate. The screen directions tell us that Henry van Cleve speaks of death "as if talking about a charming social affair," a typical Lubitsch combination of naiveté and élan.

In the end, heaven could not wait, and the death forestalled during the making of the film arrived to claim Lubitsch in 1947, after his sixth heart attack. Sadly, Raphaelson had reason to bring his eulogy for Lubitsch out of his file cabinet. Only then did he discover that his secretary had broken her vow of secrecy; Lubitsch had read the loving obituary when he had recovered from those first heart attacks, and had been deeply touched. By then he must have known that Raphaelson's feelings for him had already found a lighter but equally powerful voice in the screenplay for HEAVEN CAN WAIT.

As Henry van Cleve had said, there was a great deal of crying; the film community felt Lubitsch's passing keenly. His final film, 1948's THAT LADY IN ERMINE, was finished by his friend Otto Preminger, who asked that his own name not appear in the credits as a tribute to Lubitsch. Still, Hollywood knew that a unique voice, articulate, intense, and gentle, had been forever stilled. As the mourners left the gravesite, another European ironist had the last word. A saddened William Wyler said to Billy Wilder, "Well, no more Lubitsch." "Worse," replied Wilder. "No more Lubitsch films."