FILM NOTES

FILM NOTES INDEX

NYS WRITERS INSTITUTE

HOME PAGE

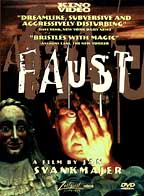

Faust

Faust

(Czech/French, 1994, 97 minutes, color, 35 mm)

Directed by Ernst Gossner and Jan Svankmajer

Cast:

Petr Cepek . . . . . . . . . . Faust

Stanislava Babicka . . . . . . . . . Dancer

Lenka Havrankova . . . . . . . . . . Dancer

Josef Podsednik . . . . . . . . . . Puppet

The

following film notes were prepared for the New York State Writers

Institute by Kevin Jack Hagopian, Senior Lecturer in Media Studies

at Pennsylvania State University:

Jan Svankmajer lives in a creaky surrealist’s castle of illusions and mortifications. That "castle" is set in a gloomy corner of Czechoslovakia in the foothills of a landscape he might have named himself: the Mountains of the Mother of God. It is a decaying manor house, forfeited to him by gypsies who had let their animals roam its hallways. There, in a personal Black Museum, with his wife, Eva, and his children, he quietly produces an outpouring of weird art in several media, including ceramics, sculpture, painting, collages, stuffed birds, bones, skulls, and even assemblages of fruit and vegetables, with the works of other artists nearly as perverse as he filling its dank cellars and silent cloisters. And there he practices the lively black arts of animation. In films such as DIMENSIONS OF DIALOGUE (1982), THE FALL OF THE HOUSE OF USHER (1980), and THE DEATH OF STALINISM IN BOHEMIA (1990), severed limbs do sprightly danses macabre and plates full of food organize themselves into anthropomorphic, psychotic pageants. FAUST (1994) is his most ambitious nightmare yet, a refashioning of one of surrealism’s sacred texts out of materials Svankmajer has had lying about the cobwebby attic of his imagination since his youth.

That youth (Svankmajer was born in 1934) was first twisted by the German occupation, and then by the long gray ennui of the Soviet epoch. Early on, Svankmajer fell into the most marvelous bad company, a band of renegade intellectuals determined to slander the rigidly idiotic Stalinist mind through allegory and absurdity. The Czech Surrealists adopted Svankmajer during his student days at the Institute of Applied Arts in the early 50s, and by the time he moved on to the Prague Academy of Performing Arts, he was thoroughly immersed in puppetry as medium of social criticism. His puppet and marionette shows at the Theatre of Masks, the Black Theatre, and the Laterna Magika in Prague made him an underground celebrity, his style shaped by figures as diverse as the surrealist painter Arcimboldo and Lewis Carroll. Svankmajer moved to animation in 1964, where he worked relatively unhindered, for his satires on official hypocrisy were so oblique that the literalist state authorities had only a faint suspicion they were being burlesqued, a suspicion they only rarely acknowledged, and then in ways that only confirmed their thickheadedness. (Svankmajer recounts with a smirk that in 1972s LEONARDO’S DIARY, he was forced to change a hockey game to a football match, because the Czechs had just drubbed the Soviets in Olympic hockey.) With his move into features in 1987, Svankmajer began painting on a wider canvas, but his vision remains as kinked and uncanny as ever.

Svankmajer caresses FAUST, savoring the story’s inherent grotesqueness. Scrambling together equal parts Gounod, Marlowe and Goethe with a tincture of Charles Addams, half opera, half comic book, Svankmajer’s FAUST becomes part of an ongoing personal project to "return art to the level of magic ritual," while at the same time "carrying on an active dialogue with my own childhood." Because that childhood was an Absurdist tapestry of sexual fantasies and material deprivation, FAUST revels in memories of repressed passions and bizarre, indulgent fancies about food and bodies, delightful perversions in which the "normal" must always come equipped with quotation marks. It is set in Prague, the ancestral home of surrealism, Kafka’s city, "a city," says Svankmajer lovingly, "of magic, alchemy, and hermetics."

Svankmajer calls himself "a militant surrealist," and this film is a wildly expressive externalizing of the unacknowledged and the unspeakable. Here, Faust is not a court figure, but a Czech everyman, a schlemiel first seen in a subway. His problem, says Svankmajer, is everyone’s: "sooner or later, everyone is faced with same dilemma: either to live their life in conformity with the misty promises of institutionalized ‘happiness’ or to rebel and take the path away from civilization, whatever the results." Svankmajer is bemused by the inanities of the well-upholstered "lifestyles" of modern capitalism, but the fear and desire begotten by this longing is a very serious matter for the storyteller: "When any civilization feels its end is growing near, it returns to its beginnings and looks to see whether the myths on which it is founded can be interpreted in new ways which would give them a new energy and ward off the impending catastrophe." But, like any mythology designed to service a particular society at a specific moment, unintended meaning slips through the leaky seams of the Faust story, says Svankmajer: "The repressive civilization it is based on brings with it so many psychological problems it deforms man’s spirit, so do the advantages of civilization sufficiently outweigh what man has lost?" This rhetorical invocation of spiritual abandonment stalks this sad and beautiful film. It is the artist’s job to be the skeleton at the feast of modernity, believes Svankmajer, and in his dedication to this responsibility, he reveals himself to be much more the moralist than the cynic.

Because the Faust story is such a core myth for humanity, Svankmajer makes his Devil man’s alter ego, a brother to the man-child, with his foibles and fleshly yearnings, and a foil for God-the-father, who is a distant and dour disciplinarian. In a strangely affective way, the Devil is the protagonist in Svankmajer’s bent but sympathetic theology.

In order to show the gravity of the choice Faust faces, Svankmajer lingers on the pure "thingness" of the objects that surround and tempt Faust. He has, he says, "a belief that places, rooms, and objects have their own passive lives which they have soaked up, as it were, from the situation they have been in, and the people who made, touched, and lived with them." Svankmajer announces through FAUST that he prefers to "deal with dead things rather than with live people. . . I am a necrophile." Somehow, in Jan Svankmajer’s FAUST, this fascination with dead things touches the living heart; like FRANKENSTEIN, it is the kind of horrific art that truly animates the human spirit.

— Kevin Hagopian, Penn State University

For additional information, contact the Writers Institute at 518-442-5620 or online at https://www.albany.edu/writers-inst.