FILM NOTES

FILM NOTES INDEX

NYS WRITERS INSTITUTE

HOME PAGE

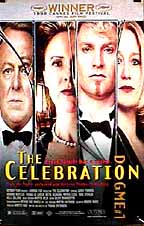

(Denmark, 1998, 105 minutes, color, 35mm)

In Danish and English with English subtitles

Directed by Thomas Vinterberg

Cast:

Ulrich Thomsen . . . . . . . . . . Christian

Henning Moritzen . . . . . . . . . .Helge

Thomas Bo Larsen . . . . . . . . . . Michael

Paprika Steen. . . . . . . . . .Helene

Birthe Neumann . . . . . . . . . . Else

The

following film notes were prepared for the New York State Writers

Institute by Kevin Jack Hagopian, Senior Lecturer in Media Studies

at Pennsylvania State University:

FESTEN’s English title, "The Celebration," is an appropriate moniker. Tonight’s film is a celebration of amateur filmmaking technology by a small but noisy coven of film luddites who believe not only that less is more, but that a lot less is a lot more. This story of a dysfunctional family is rendered in small brush strokes and a palette of grays, yet its effect is withering and raw.

Dogme (Dogma) is a Danish filmmaking group, which rejects special effects and cinematic polish. It doesn’t take a trained cinematographer to notice that the bombast and high gloss of Hollywood blockbusters has led to a precipitous decline in story values and character development. Recognizing Dogme is a group of Danish directors ring-led by Lars von Trier (BREAKING THE WAVES) and Thomas Vinterberg who decided that passive resistance to the effects-driven movie was not enough. They wrote and signed a document called "Dogme 95," a ten-point manifesto they called a "Vow of Chastity" which called for a return to bare bones filmmaking. Films made to Dogme’s rigid specs use hand-held cameras, ‘wild’ sound, available lighting, location filming (there are no sets in FESTEN), and emphatically, no digitized imagery. Even their choice to work with a video master transferred to a 35mm negative seems brash, another opportunity to lose the elegance and gloss of the ‘prestige’ foreign film. Dogme counts among its spiritual forebears the American Cinema Verité movement of the 1960s pioneered by D.A. Pennebaker, and like those provocative documentarians they see themselves as provocateurs for a newly meaningful cinema in a landscape of mediocrity. Dogme calls for a return to the profound simplicity of ‘little films’ such as THE 400 BLOWS (Truffaut, 1958), and SHOESHINE (de Sica, 1946), a cinema in which, to quote their credo, "the inner lives of the characters justifies the plot." FESTEN is the first film to embody Dogme’s passion for the miniature movie.

Dogme (Dogma) is a Danish filmmaking group, which rejects special effects and cinematic polish. It doesn’t take a trained cinematographer to notice that the bombast and high gloss of Hollywood blockbusters has led to a precipitous decline in story values and character development. Recognizing Dogme is a group of Danish directors ring-led by Lars von Trier (BREAKING THE WAVES) and Thomas Vinterberg who decided that passive resistance to the effects-driven movie was not enough. They wrote and signed a document called "Dogme 95," a ten-point manifesto they called a "Vow of Chastity" which called for a return to bare bones filmmaking. Films made to Dogme’s rigid specs use hand-held cameras, ‘wild’ sound, available lighting, location filming (there are no sets in FESTEN), and emphatically, no digitized imagery. Even their choice to work with a video master transferred to a 35mm negative seems brash, another opportunity to lose the elegance and gloss of the ‘prestige’ foreign film. Dogme counts among its spiritual forebears the American Cinema Verité movement of the 1960s pioneered by D.A. Pennebaker, and like those provocative documentarians they see themselves as provocateurs for a newly meaningful cinema in a landscape of mediocrity. Dogme calls for a return to the profound simplicity of ‘little films’ such as THE 400 BLOWS (Truffaut, 1958), and SHOESHINE (de Sica, 1946), a cinema in which, to quote their credo, "the inner lives of the characters justifies the plot." FESTEN is the first film to embody Dogme’s passion for the miniature movie.

FESTEN is a chamber drama of a family’s agony. An extended family gathers to celebrate the 60th birthday of its patriarch, Helge (Henning Moritzen). Everyone seems to have made it back to the celebration except one of Helge’s daughters, Christina. Under the ceremonial good manners lurks a festering secret about Christina’s absence. Vinterberg’s account of this family’s retreat swiftly becomes ominous, even surreal, as the kinship unit constantly splinters and reassembles itself into new alliances, focussing its nervous anxiety on new targets. With its rough-hewn style, FESTEN begins to feel like a demented little home movie. The presence of the camera is palpable and unnerving.

FESTEN is a chamber drama of a family’s agony. An extended family gathers to celebrate the 60th birthday of its patriarch, Helge (Henning Moritzen). Everyone seems to have made it back to the celebration except one of Helge’s daughters, Christina. Under the ceremonial good manners lurks a festering secret about Christina’s absence. Vinterberg’s account of this family’s retreat swiftly becomes ominous, even surreal, as the kinship unit constantly splinters and reassembles itself into new alliances, focussing its nervous anxiety on new targets. With its rough-hewn style, FESTEN begins to feel like a demented little home movie. The presence of the camera is palpable and unnerving.

FESTEN’s minimalism has been a refreshing variation in a year that has seen the release of a dozen films, which have no life outside of their special effects. Evidently, international film festival juries agree; in addition to success as an official entry at the Toronto and New York festivals, FESTEN was co-winner of the Jury Prize at Cannes.

FESTEN’s minimalism has been a refreshing variation in a year that has seen the release of a dozen films, which have no life outside of their special effects. Evidently, international film festival juries agree; in addition to success as an official entry at the Toronto and New York festivals, FESTEN was co-winner of the Jury Prize at Cannes.

FESTEN is not the first film to feature a jittery, even random-seeming frame. Since at least Roberto Rossellini’s ROME, OPEN CITY and Delmer Daves’ DARK PASSAGE, both 1945, filmmakers have been taking cameras off tripods to signify fear, surveillance, and danger. Recently, though, films such as von Trier’s BREAKING THE WAVES have used the handheld camera very differently, as a basic compositional choice. Perhaps the world we live in is now such an inherently unstable place that we need a new visual vocabulary of uncertainty to represent it.

— Kevin Hagopian, Penn State University

For additional information, contact the Writers Institute at 518-442-5620 or online at https://www.albany.edu/writers-inst.

Festen (The Celebration)

Festen (The Celebration)