FILM NOTES

FILM NOTES INDEX

NYS WRITERS INSTITUTE

HOME PAGE

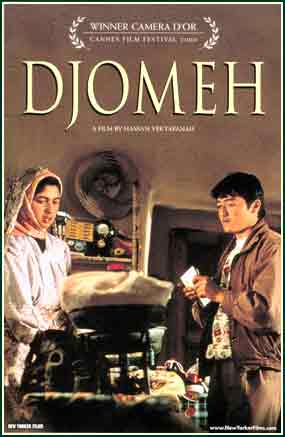

Djomeh

Djomeh

(Iranian/French, 2000, 94 minutes, color, 16mm)

Directed by Hassan Yektapanah

In Farsi with English subtitles

Cast:

Jalil Nazari . . . . . . . . . . Djomeh

Mahmoud Behraznia . . . . . . . . . . Mr. Mahmoud

Rashid Akbari . . . . . . . . . .Habib

Mahbobeh Kalili . . . . . . . . . . Setareh

High in the wind-scoured mountains of Iran, "Djomeh" (Jalil Nazari), a young Afghani, labors on a tiny farm owned by a "Mr. Mahmoud" (Mahmoud Behraznia). There, tending his dairy cows, a young man Djomeh apprentices himself intellectually to "Habib" (Rashid Akbari), an older man, and another Afghani expatriate. Patiently, Habib tutors the boy in the skills of patience and reflection, skills the years have not yet allowed the sometimes rash Djomeh. Habib has his work cut out for him; he and Djomeh's emigration from Afghanistan was hastened by Djomeh's ill-advised but passionate relationship with a woman twelve years his senior. Habib's tutelage of Djomeh in the ways of caution and circumspection, though, is not entirely successful, for the young man begins to court Setareh, the daughter of a local shopkeeper, in the face of casual racism and arbitrary custom. His is neither a patient, nor a conventional courtship -- but it is one that will endear him to audiences.

First-time director Hassan Yektapanah served his filmmaking apprenticeship with the legendary Abbas Kiarostami. "He taught me how to look at the world and think," says Yektapanah, admiringly. Yet Yektapanah's film is his own, a naturalistic and wry world, where Kiarostami's universe in films such as AND LIFE GOES ON and CLOSE-UP was an expressionistic and ironic one. DJOMEH's thoughtful observation of life in the hill country of Iran is detailed almost to the point of documentary veracity, and Yektapanah's touch with characters is a gentle one. This a humane, inwardly focused film, among whose progenitors might be the great Japanese director Yasujior Ozu, also a poet of the everyday. Like Ozu's late masterpiece OHAYO, and Vittorio DeSica's SHOESHINE, DJOMEH is a film that searches for warmth and humor in the unfolding of every new day's thousand tiny incidents, a film that makes the prosaic unforgettable.

Yektapanah is emerging as one of the Iranian cinema's great talents, a cinema that has already produced a range of exceptional films in the last 20 years. (DJOMEH won the Camera d'Or for best first film at the Cannes film festival.) The Iranian industry, like the Chinese, has flourished despite an atmosphere of official suspicion of this most Western of storytelling forms. Through indirection and parable, DJOMEH articulates not only universal concerns, but also the particular cultural anxieties of modern Iran. This quiet, insistent little film speaks both tongues with equal fluency.

— Kevin Hagopian, Penn State University

The following is excerpted from a New York Times review by A. O. Scott that appeared September 5, 2001:

Hassan Yektapanah's "Djomeh" offers the latest evidence that the spirit of Italian neorealism has taken up residence in Iran. At first glance "Djomeh," which won the Camera d'Or (for best first feature) at the 2000 Cannes International Film Festival, is a simple, almost anecdotal story embedded in the daily rhythms of rural life in a dusty, mountainous corner of Iran. But on reflection it proves to be an investigation, at once lucid and enigmatic, of exile, loneliness and the fragile possibility of friendship.

Hassan Yektapanah's "Djomeh" offers the latest evidence that the spirit of Italian neorealism has taken up residence in Iran. At first glance "Djomeh," which won the Camera d'Or (for best first feature) at the 2000 Cannes International Film Festival, is a simple, almost anecdotal story embedded in the daily rhythms of rural life in a dusty, mountainous corner of Iran. But on reflection it proves to be an investigation, at once lucid and enigmatic, of exile, loneliness and the fragile possibility of friendship.

Mr. Yektapanah has said that Abbas Kiarostami, the Iranian director with whom he worked on "The Taste of Cherry," "taught me how to look at the world." The lessons are evident in the sense of landscape in "Djomeh" and in its quiet, contemplative pace. But Mr. Yektapanah's way of looking is also more naturalistic and emotionally direct than Mr. Kiarostami's sometimes is, and his manner not quite so oblique and self-reflective as his mentor's can be.

The film's title character, a young man from Afghanistan who is a hired hand on a dairy farm, is a guileless and sweet-natured romantic. Unlike other Afghan emigrants, he has not come to Iran primarily to escape his country's perpetual civil war or to make money but because his impulsive courtship of a widow back home compromised his family honor. In spite of his limited means and humble status, Djomeh (Jalil Nazari), who is treated with condescension and suspicion by the townspeople whose milk he buys, falls in love with Setareh (Mahbobeh Kalili), the daughter of a shopkeeper, and enlists the help of his employer, Mr. Mahmoud (Mahmoud Behraznia), in his efforts to win her hand.

Whether his affections are reciprocated is impossible to know, since local customs and government censors restrict the interactions between unmarried men and women. And Mr. Mahmoud, a sympathetic older bachelor who is Djomeh's only real confidant, is skeptical of the young man's ardor, wondering if he wants to be married simply because, in Afghanistan, that's what a man of 20 is expected to do.

More than passion or obligation, Djomeh's longing to be married seems to be a response to the lonely marginality of his circumstances and an expression of his desire to belong, to find a spot for his loving, openhearted nature to take root. It seems that every day, when he and Mr. Mahmoud arrive in Setareh's village, they encounter a wedding procession, a celebration of social cohesion that only underscores Djomeh's position as an outsider.

While his infatuation with Setareh gives the film its narrative shape - the daily routine of loading cans of milk and caring for sick cows is interrupted by Djomeh's ill-timed, unnecessary errands to her father's shop - the emotional core of the film is his friendship with Mr. Mahmoud. Their closeness irritates Habib (Rashid Akbari), Djomeh's older kinsman and designated guardian, whose brusqueness is a bad match for his relative's dreamy temperament (but who nonetheless is given the film's last words of homely wisdom). Every morning Djomeh and Mr. Mahmoud ride together in the cab of a pickup truck, and much of "Djomeh" is devoted to their conversations, in which a quiet warmth shines through the formal courtesies and tactful silences. Courtesy and tact might also describe Mr. Yektapanah's approach to filmmaking. When the tension between Habib and Djomeh boils over into a fight, the camera leaves the room and waits outside. And the film's climactic scene, in which Mr. Mahmoud returns from his meeting with Setareh's father, is played with a matter-of-fact subtlety so exquisite that its undertones of feeling are almost inaudible. But such restraint only serves to enrich the experience of watching "Djomeh"…. The final half-dozen shots are like the well-chosen final sentences of a short story that suddenly reveal the depth and complexity of the plain prose that has come before.

The following is excerpted from a Village Voice review by J. Hoberman that appeared August 31, 2001:

Balanced on a knife-edge between the exotic and the familiar, Djomeh is among the most formally accomplished of new Iranian films. Hassan Yektapanah's dryly comic first feature-which shared the Camera d'Or with A Time for Drunken Horses at the 2000 Cannes Film Festival-enriches a deceptively anecdotal plot with a combination of observational camerawork, strong narrative rhythms, and deft characterization. Djomeh's eponymous protagonist is a 20-year-old Afghani exile working on a dairy farm in the mountains of northern Iran and known to the locals mainly as the "milk boy." His middle-aged Iranian boss, Mahmoud, assumes that Djomeh left Afghanistan for economic reasons or perhaps to escape civil war, but the milk boy's motivations turn out to be personal-he departed his homeland as a result of an unhappy, or at least inappropriate, romantic involvement, having fallen in love with a widow 12 years his senior.

This revelation emerges during the course of the four lengthy discussions that Djomeh has with Mahmoud, riding beside him in a battered pickup truck as they drive the dusty road, village to village, collecting milk from the townspeople's goats and cows. Djomeh professes his surprise that Mahmoud, who appears to be in his early forties, is still single. In Afghanistan, he explains, the boss would already be a grandfather; why, Djomeh asks, do Iranians postpone their marriages? We might also wonder-one of the movie's recurring motifs has Djomeh and Mahmoud coming across a wedding procession in nearly every trip to town.

Djomeh's curiosity about Iranian marriage customs is not theoretical. It's soon revealed that he has his eye on the demure young girl who, forever adjusting her chador, works behind the counter in a village grocery store. Djomeh's travels with Mahmoud are counterpointed by the boy's carefully orchestrated solo visits to this store. Eager to extend his permitted time with the largely silent girl, he routinely overpurchases canned goods. (This, in turn, contributes to Djomeh's ongoing conflict with his irascible older kinsman, an economic refugee who also works for Mahmoud and sends money home to his family.)

As the naive Djomeh, Jalil Nazari scarcely seems to be acting. His ardent attack on the dialogue in every scene underscores his role as a foreign yokel in more sophisticated Iran. Nazari's broad, open face could have been made to express persistence. Despite the regular taunts of the village kids, Djomeh seems oblivious to the local prejudices against foreigners. (There's an effortlessly metaphoric bit of business which has one mischievous urchin using a piece of mirrored glass to reflect the sun into a blind man's unseeing eye.) Djomeh is earnest, a bit clumsy, and utterly single-minded. In another age, this story would have been titled The Passionate Milk Boy. By contrast, Mahmoud Behraznia-who plays the grizzled, homely boss-comes across as the film's only professional actor, his experience belied by the affable quips and significant silences that largely go over his young employee's head….

The 38-year-old Yektapanah served as an assistant director for both Abbas Kiarostami on Taste of Cherry and Jafar Panahi on The Mirror; Djomeh isn't overtly self-reflexive but feels strongly reminiscent of Kiarostami in its compositions and pacing. Yektapanah's camera is largely static, and he makes evocative use of offscreen sound. (There's a constant, reproachful moo throughout most of the action.) Extremely process-oriented, the film has been designed as a rondo of mundane tasks (weighing milk, caring for cows) and routine interactions; the drama of this rueful not-quite-romance is skillfully grounded in a series of graceful repetitions. Ultimately Djomeh is a movie about the yearning for what one cannot have. It's a universal theme, but where, outside of Iran, do we see this unforced economy of expression?

For additional information, contact the Writers Institute at 518-442-5620 or online at https://www.albany.edu/writers-inst.