FILM NOTES

FILM NOTES INDEX

NYS WRITERS INSTITUTE

HOME PAGE

Field of Dreams

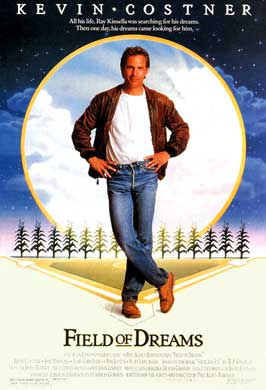

Field of Dreams

(American, 1989, 107 minutes, color, 16 mm)

Directed by Phil Alden Robinson

Cast:

Kevin Costner . . . . . . . . . . Ray Kinsella

Amy Madigan . . . . . . . . . . Anni Kinsella

Gaby Hoffman . . . . . . . . . . Karin Kinsella

Ray Liotta . . . . . . . . . Shoeless Joe Jackson

James Earl Jones . . . . . . . . . . Terence Mann

Phil Alden Robinson’s appearance at the Institute is rescheduled for October 2002 because of commitments on his current film, The Sum of All Fears.

In 1951, my friend Eric's father died. Eric's dad was a pilot. He'd spent World War II flying C-47's "Over the Hump," in Burma. He survived some of the most dangerous fIying of the war only to be killed at a peacetime airport when a flight student couldn't pull a plane out of a practice stall. Eric was six years old when his father died.

Eric grew up to be a top athlete, and a professional ballplayer, pitching in the California Angels organization. Today, he's a certified art therapist who's helped thousands of people, sick in mind or body, to see the world, and themselves, more clearly through painting and photography. He's an absolutely great guy, big, jovial, perpetually laughing and smart-assing it up, a man who likes his jokes noisy and his shirts even louder. And yet, you have to be careful with him on one subject. You learn not to talk much around Eric about your own father, and about the simple rituals with Dad that you took for granted as a kid, the little passing moments of maleness between two guys that seemed so unimportant at the time but turned out to be the apprenticeship for your own manhood. Eric's angry about missing those ordinary transactions of masculinity, and his face clouds over when you forget, and mention your own father. He gets quiet. "I never got to play catch with my Dad," he says, and after a moment of uncomfortable silence, you go on to something else.

Field of Dreams is a film about lost chances gotten back again, and about finally having those talks with Dad you wish you'd had. The story of "Ray Kinsella's" (Kevin Costner) crusade to bring a perfect ballyard to his Iowa cornfield is an unashamed parable of male longing, an excusably sexist paean to a universe untroubled by the emasculating realities of corporate economics, and by the withering of skill that comes with age.

In baseball, Ray Kinsella finds redemption for himself by connecting his own baseball past with the game's own mythic figures. He travels to Boston to rescue a misanthropic, reclusive writer "Terence Mann" (James Earl Jones, in a character famously modeled on The Catcher in the Rye author J.D. Salinger) with a trip to Fenway Park, and the two then travel deep into the wilds of Minnesota to collect one Archie "Moonlight" Graham, heretofore only the answer to a trivia question. Moonlight turns out to be an elderly Main Street hero, and Ray helps to satisfy his last unfulfilled desire. Finally, back at the farm, the game itself is redeemed, and a long-ago off-the-field injustice is righted where it should be: on the diamond. And, as a coda, there is Ray's own father, a dimly-recalled figure made real again through baseball.

Field of Dreams can be rightly criticized for its sentimentality, and its willingness to resolve the most vexing human problems through a ballgame with the Mount Olympus All-Stars. At the end, the film's disturbing reaffirmation of capitalism as a kind of American spirituality is jarring, but even that is oddly fitting. Baseball has always, even in the golden years that are the subject of Field of Dreams, been a business, often a notably cruel one. Lock-outs, teams holding up cities for new stadiums, Croesus-like owners pleading poverty, the home town slugger skipping to a new team every time the crocuses bloom; increasingly, we know that baseball isn't a metaphor for life, but simply life itself, complete with cleats and a jockstrap.

It's wrong to call Field of Dreams a baseball film; like the best baseball films, Bang the Drum Slowly, Billy Crystal's recent 61, or Ron Shelton's sublime Bull Durham, this is a film that knows that baseball is a place in a boy's memory where the rules are clear, where the soda pop is always ice-cold, and where there's always the chance of an autograph from Mickey Mantle. Most of all, it's a man's world, where the men seem just like the gods. There they stand, muscles moving subtly under their numbered jerseys, talking easily with one another, jogging up the steps of the dugout, loosely swinging a cluster of bats in the sunshine, casually jerking batting practice home runs into the distant bleachers. And you, the kid in the seats along the first-base line with your father, are not a mere spectator in this human comedy. You've brought your glove, in case you're asked to field a foul ball. You and your father speak of what might happen next -- a bunt, a steal, a hit-and-run. You speak of what just happened -- a triple off the wall in left center, a force play at second, a called strike right down the pipe. Finally, you speak of what might have happened, as you leave the park sunburned and sticky, bloated with too many Cokes and hot dogs, and serenely happy. In this green place in the city, on this summer afternoon, you have known both hope and despair, faith and cynicism. You have gone to this man's place with your father, and you have begun to find your own voice in that distinctively male discourse composed of one part bravado, one part leg-pulling, and one part regret, that way of being male that is simultaneously loud and silent. To paraphrase Raymond Carver, what we talk about when we talk about baseball is nothing less than a conversation, by turns loving and competitive, about manhood itself.

I toss the ball to my friend Eric, and he catches it, big-knuckled and loose-limbed. The look of the ex-ballplayer is there in the set of his shoulders, and the way he squints confidently into the sun. Like all men who weren't good enough, I envy that look. And yet there is that in him which envies me. He tosses the ball back, but for him, it's not the same.

— Kevin Hagopian, Penn State University

The following is taken from an article by Nina Easton that appeared in the Los Angeles Times, April 21, 1989:

No matter how hard Universal Pictures tries to hide it, "Field of Dreams" is a baseball movie. A title change (from "Shoeless Joe") and full-page advertisements that don’t even mention the sport can’t mask the fact that at the center of the story stands Shoeless Joe Jackson—wistfully recalling the "smell of the ballpark in my nose and the cool of the grass on my feet. The thrill of the grass. . . ."

No matter how hard Universal Pictures tries to hide it, "Field of Dreams" is a baseball movie. A title change (from "Shoeless Joe") and full-page advertisements that don’t even mention the sport can’t mask the fact that at the center of the story stands Shoeless Joe Jackson—wistfully recalling the "smell of the ballpark in my nose and the cool of the grass on my feet. The thrill of the grass. . . ."

The Chicago "Black" Sox left-fielder was forever suspended from major league baseball for his part in a scheme to fix the 1919 World Series. In "Field of Dreams" he returns to life when an Iowa farmer (played by Kevin Costner) tears up his cornfield to build a baseball diamond.

But "Field of Dreams," based on W.P. Kinsella’s book "Shoeless Joe," is about a lot more than baseball. It’s also about lost dreams, generational ties and discovering magic in the back yard. So director Phil Alden Robinson can be excused when he interrupts an interview about his new film and the role of baseball in American life, and insists that he needs to explain the "Robinson theory of my generation."

"We’re the first generation in this century not to divest ourselves at 21 of those things that defined us as teenagers," Robinson, 39, says of the baby-boom generation. "We still maintain as options a willingness to wear jeans, to question authority, to listen to rock ’n roll. We’ve maintained all those things that defined us as teens. I think that’s healthy."

But teen-age dreams—whether visions for life or just those crazy impulses that seemed to define the 60s—had a rougher time surviving the wear and tear of the years, says Robinson.

In "Field of Dreams,"" Costner’s character, Ray Kinsella, builds the ball field for Shoeless Joe after hearing a voice in his cornfield say, "If you build it, he will come." Later, he nearly loses his farm as he sets off on a cross-country search for a famous reclusive author (played by James Earl Jones) and another old baseball pro (Burt Lancaster). Again, because a voice told him to.

"When you’re 19 or 20 and you want to do something crazy you do it," Robinson says. "I’ve struggled a lot with the whole issue of what you do with your dreams (as an adult)," he adds. "I like to believe that there’s still a way to hang onto the same kind of freedoms." Robinson then recalls the time that he and his college roommates draped a parachute across a flagpole outside their house and not one neighbor in that working-class section of Schenectady, N.Y. raised a fuss.

In writing the screenplay for "Field of Dreams," Robinson said he attempted to stay as close as possible to Kinsella’s dialogue in the book, which has become a cult favorite among baseball fans. But he added one speech in which Costner describes his fear of turning into his father, a man who always seemed old, who had stopped dreaming long before his son arrived on the scene.

When Costner’s character hears a voice early in the film, he’s ready to listen. "Here’s a guy in his late 30s, presented with the choice of doing something completely illogical," Robinson says. "Taking that step into the void symbolized who we are, our legacy of the 60s."

But Robinson also makes sure that Costner’s character finds much of his dream at home, in his wife (Amy Madigan) and daughter (Gaby Hoffman). That, too, is part of the Robinson theory on the baby-boom generation.

"We’re now going through a second coming of age," the director says. "We’ve deferred what it means to be grown-ups," including marriage and children. This is not just idol philosophizing: Robinson himself is ready to look inward, to focus on friends and family. "I’ve deferred life for my career," says the unmarried director. So, after the release of "Field of Dreams," . . . Robinson is taking a year-long sabbatical to focus on friends, family, relationships. "Read my lips," he says, "no more movies."

"We’re now going through a second coming of age," the director says. "We’ve deferred what it means to be grown-ups," including marriage and children. This is not just idol philosophizing: Robinson himself is ready to look inward, to focus on friends and family. "I’ve deferred life for my career," says the unmarried director. So, after the release of "Field of Dreams," . . . Robinson is taking a year-long sabbatical to focus on friends, family, relationships. "Read my lips," he says, "no more movies."

By doing so, Robinson will be walking away from Hollywood—if only temporarily—at a time when his career is taking off. After studying political science at Union College in Schenectady, Robinson worked briefly as a journalist and then for many years produced, wrote and directed industrial and educational films.

His big break in Hollywood came just five years ago, when his comedic screenplay "All of Me," directed by Carl Reiner and starring Steve Martin and Lily Tomlin, became a critical and commercial hit. Robinson also wrote the original screenplay for another film that year, "Rhinestone," starring Sylvester Stallone and Dolly Parton. But when that film was released to almost unanimous critical scorn, Robinson went public with the fact that Stallone had completely rewritten it.

If early reviews are any indication of audience reaction, "Field of Dreams" is likely to polarize audiences. Syndicated film critic Roger Ebert calls the movie "completely original and visionary." But Time magazine’s Richard Corliss sees it as a "male weepie at its wussiest."

Robinson first tried to launch the project in 1982 after Kinsella’s book was published, but he couldn’t generate much interest. "The general response was, ‘We can see why you love this book but you can’t make a movie out of it,’" he recalls.

The "Shoeless Joe" project first wound up at Fox, but that studio ultimately decided not to make it. Together with the brother producer team of Lawrence and Charles Gordon, Robinson took his screenplay to Universal. As they were closing the deal, Universal motion picture group chairman Thomas Pollock joked, "This was the kind of movie that you only make if you hear a voice telling you to."

Robinson responded, "If you make it, they will come."

Costner was the first actor to come to mind for the lead, says Robinson, but he and the producers were so sure he wouldn’t be interested in doing another baseball movie after "Bull Durham" that they didn’t even add his name to their list. A Universal executive, however, made sure the script got in Costner’s hands, and he came to them.

"It was a great, great screenplay," Costner recalls. "I saw and believed in the fantasy of this movie."

Costner said he "wasn’t at all worried about" appearing in another film about baseball. But he admits that among his advisers "there was some concern about it." Costner promised to back up Robinson if the studio began tinkering with the film’s fantasy elements and dialogue. But they never came to blows with Universal—until the studio, concerned about the bleak fate of past baseball movies at the box office, changed its title to "Field of Dreams."

"I loved the title ‘Shoeless Joe’; It’s a title for a movie about dreams deferred," Robinson says, recalling the lost dreams of the innocent Shoeless Joe at the hands of baseball’s corrupt owners. Robinson fought and fought, but Universal wouldn’t budge on the title change. Finally, the day came when the director had to break the bad news to the book’s Canadian author, Kinsella. Robinson recalls that he felt sick as he dialed the phone.

But Kinsella took the news in good humor: "Shoeless Joe" had been the publisher’s idea for a title, Kinsella told Robinson. They thought it would sell better. Kinsella had always wanted to call his book "The Dream Field."

The following is taken from an article that appeared in the Los Angeles Daily News, June 17, 1989:

Director Phil Alden Robinson struggled for five years to make "Field of Dreams." It was, as the saying goes in Hollywood, his "dream project." Then the dream turned into a nightmare, an experience so bad that Robinson is taking a leave of absence from the film business.

"It was painful," Robinson recalled. "When we were on the set, I was saying practically every day, ‘I will never do this again.’ I was just really overwhelmed by the difficulty of the job. You’re just constantly surrounded by doubt, mostly your own."

"And it turned out to be a much more physically difficult movie than any of us imagined—we were shooting during a drought, which was very depressing, to see these farmers all around us not being able to grow their crops."

"It was very physically uncomfortable—105 degrees and very humid. . . . And we had an extremely difficult schedule all based on the projected growth of the corn."

But the corn wouldn’t grow.

Kevin Costner had to leave to make another film on Aug. 15. James Earl Jones was back and forth to "Three Fugitives," which he was shooting simultaneously. Burt Lancaster had a commitment in Europe, Tim Busfield had one to TV.

And the corn wouldn’t grow.

They shot everything else they could, interiors and scenes outside the farm, waiting for nature to take its course. Nature didn’t. "I said, ‘The first scene in the movie, when Kevin hears the voice, it’s got to be up to his shoulders.’ Two weeks before we hit the corn (scenes) it was ankle high."

Robinson’s movie had gotten caught in a drought—the worst drought since the days of the dust bowl. Desperate, Robinson dammed up a stream and drenched his fields, using all his planned emergency days to buy extra time. By stretching his schedule 10 days (he ended up two weeks over budget) and pouring a small fortune into irrigation, he managed to get shoulder-high corn.

Happily, all the efforts paid off. The movie opened to solid profits, albeit in a so-far limited release, and Robinson was especially gratified by the individual responses of audience members.

"One guy said, ‘I’m going through tough times, and I needed something to make me believe, and this film has done it.’ A lot of people say, ‘I haven’t talked to my folks for a while; I’m going to call my dad.’ So a year or two years of agony was absolutely worth it."

For additional information, contact the Writers Institute at 518-442-5620 or online at https://www.albany.edu/writers-inst.