FILM NOTES

FILM NOTES INDEX

NYS WRITERS INSTITUTE

HOME PAGE

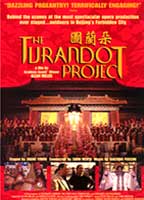

(American/German, 2000, 87 minutes, color, 35mm)

Directed by Allan Miller II

Starring:

Lando Bartolini, Barbara Hendricks, Zubin Mehta, Zhang Yimou

The following is excerpted from a review by Kenneth Turan that appeared in the Los Angeles Times, September 14, 2001:

When Zubin Mehta decided in 1997 to mount a new production of "Turandot," the Puccini opera set in Beijing’s Forbidden City, he knew exactly what he didn’t want. "Usually, ‘Turandot’ is full of cliches; it looks like a big Chinese restaurant," the conductor explains. "I wanted a China the outside world had never seen before. I said, ‘Why not a Chinese director?’ I didn’t know his name, but I said ‘Why don’t we get the "Raise the Red Lantern" guy?’"

As followers of international film know, "the ‘Raise the Red Lantern’ guy" is Zhang Yimou, one of China’s very best and most controversial filmmakers. His involvement as director was a stroke of genius for Mehta’s production, and a stroke of luck for "The Turandot Project," Allen Miller’s fascinating documentary on the ins and outs of this most unusual operatic collaboration. Though Miller is a veteran of this form, having directed 35 nonfiction musical films including the Oscar-winning "From Mao to Mozart: Isaac Stern in China" and the documentary short that was the inspiration for the Meryl Streep-starring "Music of the Heart," what he has done with "The Turandot Project" is not what you might expect.

For one thing, though there is a considerable amount of music here, it’s not the film’s major thrust. This is partly because there was so much else to focus on, and partly because the demands of this production mandated three separate sets of singers, which dilutes the interest in specific voices. It’s an hour into the film, for instance, before the tenors who sing the opera’s most famous aria, "Nessun Dorma," are introduced.

"The Turandot Project" is more concerned, and with good reason, with the opera’s extravagant visual look. The gorgeous pageantry of sets and costumes is frankly dazzling; as Mehta says, "In Asia, festivity means color. You’ve never seen a gray dragon." And you won’t see one here.

The film focuses most, however, on the unexpected areas of dramatic interest and conflict that opened up when the production, initially scheduled only for Florence, was given official permission to be remounted in Beijing.

Because of the nature of the government and the size of its bureaucracy, everything in official China is difficult. Negotiations for the project took months, and even location scouting in the production’s ultimate site, a structure in the Forbidden City, had to be conducted in secret. And because the building in question is a national treasure, one of the officials involved matter-of-factly admits, "In case something happens, I will be put in jail."

Because of the nature of the government and the size of its bureaucracy, everything in official China is difficult. Negotiations for the project took months, and even location scouting in the production’s ultimate site, a structure in the Forbidden City, had to be conducted in secret. And because the building in question is a national treasure, one of the officials involved matter-of-factly admits, "In case something happens, I will be put in jail."

Taking the production to China also thrust Zhang, more or less a trainee in Florence, right in the center of things. And because he was open to having Miller’s cameras follow him almost everywhere, we get an excellent glimpse of this exceptional director at work. Though opera and cinema are different in many ways, "The Turandot Project" still conveys a strong sense of what Zhang must be like behind the camera.

While for the Florence production, the director had gone with Peking opera-influenced costumes spanning several eras of Chinese history, he felt this would not do for the Forbidden City. Since the opera would be staged in front of a Ming Dynasty building, everyone would have to be wearing the appropriate Ming Dynasty costumes.

This was a lot easier to say than to do. Nine hundred costumes had to be made, occupying 100 rural extended families (something like 2,000 people) for four months. The cost: $600,000, which is one of the reasons the final bill for this "Turandot" crept up to $12 million to $15 million. There’s a lot you can accomplish if cost is no object.

Because of the large courtyard space between the stage and the audience, Zhang decided to make use of 300 soldiers from the Chinese army, all of whom were costumed and warned not to flirt with the ballet dancers. Western opera was new to them ("like a cow’s moaning" was one description), but they warmed to the situation.

Though he seems to have gotten along splendidly with Mehta despite the lack of a language in common, Zhang had his share of conflicts, many of them shown on-screen. The most vivid was with Italian lighting designer Guido Levi, who objected to the unnuanced brightness that Zhang championed as more in keeping with Chinese tradition. One of "Project’s" best scenes has these two standing next to each other, communicating through an interpreter but in truth not communicating at all.

Through it all, Zhang comes across as low-key but very sure of himself, as principled as he is determined. Again and again, in pep talks he gave to stagehands and in general conversation, he emphasizes that he had taken the project on "to show Chinese traditional culture to the world, to win credit for the Chinese people." To see this passion playing out, to experience how much this production did mean to China, allows "The Turandot Project" to attain levels of emotion that complement those of Puccini’s classic.

The following is taken from a brief synopsis of Puccini’s opera that appears in the production notes on the Turandot Project website:

Set in ancient China, the opera opens in front of the very walls of the Forbidden City in which the Mehta/Zhang performances take place. The vengeful Princess Turandot has decreed that anyone seeking her hand in marriage must answer three riddles or die. Many princes local and foreign have tried, failed, and been summarily executed, their heads displayed before the crowd.

Calaf, a foreign prince in disguise, is struck by Turandot’s beauty and resolves to win her, despite the pleas of his blind father Timur, who has fled his native country and come to Peking in disguise. He is attended by the slave girl Liu, who has loved Calaf from afar. She begs Calaf not to attempt the riddles. Three ministers, Ping, Pang and Pong also try to dissuade Calaf, but he is inflamed by Turandot, and he strikes the gong three times, declaring his candidacy….

The following list of curiosities regarding the history of Puccini’s opera appears on the Italian website, the Opera Web at www.opera.it :

UNFINISHED

Turandot was left unfinished by Puccini, who died in Brussels on April 28, 1924 because of complications following surgery that had successfully removed a malignant throat cancer, provoked by his bad habit of continuously smoking cigars. Puccini left many sketches of Turandot’s end: its composition stalled due to problems in concluding at the same high musical level a story that was dramatically not credible, and Puccini had years of conflicts with libretto writers.

A DYING ARTIST

Puccini confessed to a nun in Brussels’ hospital: "The artist suffers more than other people. I still have so much things to do and my soul cries thinking of not being able to succeed in doing them! You see, I have my manuscripts with me but I cannot work on them. But you cannot understand how tormented I am!"

THE REAL END

When Puccini died the final composition and orchestration of Turandot had reached the end of Liù’s death scene. This is a signal of the real ending in Puccini’s mind, typical of all his operas: the heroine’s death. The happy ending between Turandot and Calaf, with the unlikely "miracle kiss", may well have displeased the composer. The opera was finished by Franco Alfano using Puccini’s sketches, which contained all the final duet scored for voices and piano.

TOSCANINI RESPECTS THE MAESTRO

At Turandot première, performed at Teatro alla Scala on April 25, 1926, Arturo Toscanini stopped conducting in the very bar where Puccini himself stopped. He turned towards the audience and said: "Here ends Giacomo Puccini’s opera". After a long moving silence, from the stalls a spectator cried: "Viva Puccini!," and a never ending applause started. That spectator was the young conductor Gino Marinuzzi. After the long standing ovation the audience started leaving the theater. The finale written by Franco Alfano was performed only in the following performance, the day after.

TOSCANINI DOES NOT RESPECT ALFANO

The organization of the first Turandot performance was completely guided by Toscanini, who refused the first version of the finale written by Franco Alfano. Maestro Alfano composed a second version that was at last accepted and performed on the second night. But Toscanini considered it to be only "less bad than the other". In fact after rehearsing the new version Alfano asked Toscanini what he thought about it, and the conductor answered: "I saw Puccini coming in and slapping my face!".

For additional information, contact the Writers Institute at 518-442-5620 or online at https://www.albany.edu/writers-inst.