FILM NOTES

FILM NOTES INDEX

NYS WRITERS INSTITUTE

HOME PAGE

The Wild Party

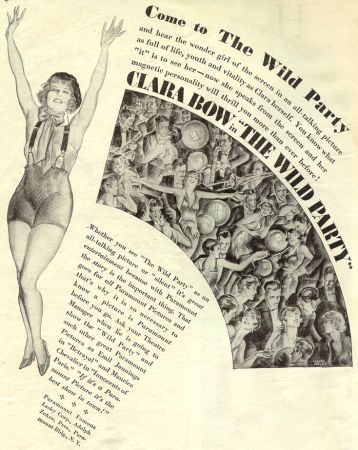

The Wild Party

(United States, 1929, 76 minutes, b&w, 16mm)

Directed by Dorothy Arzner

Cast:

Clara Bow . . . . . . . . . . Stella Ames

Frederic March . . . . . . . . . . James "Gil" Gilmore

Marceline Day . . . . . . . . . .Faith Morgan

The

following film notes were prepared for the New York State Writers

Institute by Kevin Jack Hagopian, Senior Lecturer in Media Studies

at Pennsylvania State University:

Of the significant female directors in the first 60 years of the American cinema, four names stand out: Alice Guy Blache, early pioneer of the narrative cinema, Lois Weber, wry satirist of sexual mores in the `teens and twenties, Ida Lupino, actress-director of female-centered social problems films in the late 1940’s and 1950’s – and Dorothy Arzner, perhaps the most remarkable of women directors before the 1980’s.

Arzner transformed the most prosaic material into subversive critiques of established assumptions about gender. 1940’s Dance, Girl, Dance started out as a backstage "B" melodrama, but Arzner turned it into a disconcerting, almost Brechtian meditation on male voyeurism. 1933’s Christopher Strong began as a novelty piece about a woman flyer, and came to the screen as a surreal tragedy about the price women pay to follow a nontraditional calling. Likewise, The Wild Party could have been a conventional "flapper film" in which a giddy young society woman momentarily strays from her accepted social role, but then recants her independence for marriage and family. Instead, in Arzner’s hands, The Wild Party becomes a spirited analysis of the pitfalls of gendered conformity.

Although women were particularly active as editors and scenario writers when Arzner came into the industry, there were very few women directing. As the most prolific female director in Hollywood during her long career (1927-1943), Arzner was treated as a curiosity by studio publicists. Photos of her in short hair and slacks made her, along with Katherine Hepburn (who she directed in Christopher Strong) and Marlene Dietrich, among the film colony’s most talked-about women. She deftly deflected questions about her sexuality during the early 1930’s when, according to author William J. Mann, Hollywood was actively purging gay and bisexual stars like William Haines and Ramon Navarro. Working at several studios, Dorothy Arzner directed some of the strongest female actors in the history of the medium; in addition to Hepburn, Joan Crawford, Rosalind Russell, Ruth Chatterton, Claudette Colbert, and Lucille Ball all starred in Arzner’s films, all doing some of the best work of their careers.

In The Wild Party, Arzner worked with the incomparable Clara Bow, the silent screen’s great icon of sexual freedom and passion. (The two had collaborated previously on 1927’s Get Your Man.) The Wild Party’s scenario was not based on the notorious William Moncure March long poem about a mad gin party, recently made into a Broadway show. Instead, the source material, as was the case with so many of Arzner’s films, was more ordinary, in this case a story by now-forgotten bestselling novelist of `20’s manners Warner Fabian, adapted by Samuel Hopkins Adams. The Wild Party begins as a flirtatious comedy about a group of female college students and their male paramours. Calling themselves "The Hardboiled Maidens," the women playact as sexual adventuresses, but finally reaffirm their conventional morality when a mistaken identity complication scandalizes a quiet, serious female student.

This was boiler plate stuff in 1929, but Arzner and Bow deeply undercut this routine plot. The film’s female homosociality is subtle and deeply felt, and The Wild Party portrays college not as a harmless setting for undergraduate hi jinks, but as a repressive institution bent on stifling unconventional behavior. Fabian’s story, like many flapper novels and films, is an admonition against transgressions of gender norms, but Arzner’s film explores the hypocrisy of these "rules," presenting them as a psychologically confining double standard.

By 1929, when the film was released, Clara Bow’s status as The "It" Girl had taken on a decidedly renegade tinge, with apocryphal stories about her sexual escapades circulating just below the surface of polite society. The Wild Party, as scholar Judith Mayne notes, insists that Bow’s legendary attractiveness had a homosexual as well as a heterosexual aspect.

The Wild Party’s possibilities as a proto-feminist text have been overwhelmed by the other narrative that is told about it: it was Clara Bow’s first sound film, and the experience, according to her biographer, David Stenn, was terrible. Her studio, Paramount, disturbed by Bow’s personal difficulties and increasingly reckless behavior, made the transition to sound a needlessly traumatic experience for the emotionally fragile Bow, whose voice was (contrary to legend) well-adapted to talkies. Bow gained weight, and began to behave even more erratically. Although she would make nine more films before her premature retirement from the screen in 1933, Clara Bow’s career effectively died with sound. Under the tutelage of the patient Arzner, The Wild Party is testament to what might have been for Bow, had she been allowed to mature as an actor. Her "Stella Ames" is a warm, good-humored, sexy, and loving character, as compassionate as she is passionate.

Arzner left feature film directing after a near-fatal case of pneumonia. She directed short films for the Women’s Army Corps during World War, created an innovative radio show, and became an influential film educator. Arzner made her last film more than 60 years ago, but her sophisticated revisionism of Hollywood norms, both on- and off screen, remains a call to a thoughtful and empathetic women’s cinema.

— Kevin Hagopian, Penn State University

For additional information, contact the Writers Institute at 518-442-5620 or online at https://www.albany.edu/writers-inst.