FILM NOTES

FILM NOTES INDEX

NYS WRITERS INSTITUTE

HOME PAGE

Directed by Humerto Solas

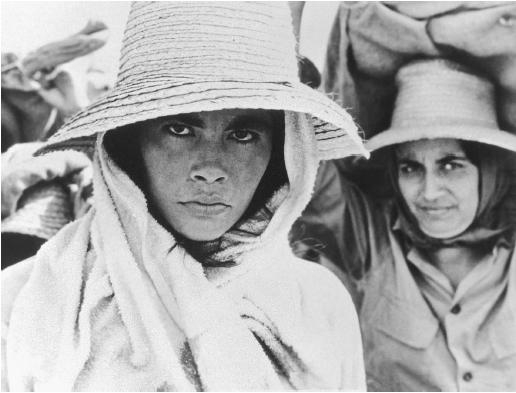

(Cuba, 1968, 161 minutes, b&w, 16mm)

In Spanish with English subtitles

Cast:

Racquel Revuelta……….Lucia

Eslinda Nunez……….Lucia

Adela Legra……….Lucia

The

following film notes were prepared for the New York State Writers

Institute by Kevin Jack Hagopian, Senior Lecturer in Media Studies

at Pennsylvania State University:

One of Fidel Castro's first acts in the wake of the success of his peoples' revolution in 1959 was to set in motion the founding of ICAIC, the Cuban Film Institute. Like the massive literacy campaign he began soon after, ICAIC was tangible evidence of Castro's belief in the interrelatedness of cultural and political change. With the example of the Soviet Union in the 1920's undoubtedly in his mind, when, in Lenin's much quoted aphorism, film became `the most important art' in pursuit of mass education and persuasion, Castro set out to make Cuban cinema a voice of engaged political discourse, a way of speaking Cuba around the world. During the 1960's, with masterworks like Tomas Gutierrez Alea's Memories of Underdeveloment, and Humberto Solas' Lucia, the revolutionary Cuban cinema joined the work of international filmmakers such as Jean-Luc Godard and Dusan Makavejev in articulating a new relationship between the personal and the political. The life of the woman Lucia becomes an allegory for the Cuban national move away from colonialism and toward liberation from the confinement of a bourgeois worldview. Lucia locates the Cuban struggle in the figure of a woman who is at once politically symbolic and specifically human; in this productive tension, Solas created one of the most important works in the nascent feminist cinema of the period.

Told in three segments, set in 1895, 1932, and in the heady years just after the Revolution, Lucia is an epic of Cuban history. The three Lucias are literally, different women, each of their stories combining into a larger narrative of slow, painful progress for Cuba, less as a nation than as a society. The three Lucias each offer different visions of class; Solas deftly links concern with economic materialism to character growth and change, in the process transforming that often very bourgeois cinematic genre, the family melodrama, into a platform for social investigation. Solas has made a cinematic political tract that simultaneously offers an inquiry into the strategies of our identification and sympathy for cinematic characters, making these novelistic creations a vehicle for political understanding.

Told in three segments, set in 1895, 1932, and in the heady years just after the Revolution, Lucia is an epic of Cuban history. The three Lucias are literally, different women, each of their stories combining into a larger narrative of slow, painful progress for Cuba, less as a nation than as a society. The three Lucias each offer different visions of class; Solas deftly links concern with economic materialism to character growth and change, in the process transforming that often very bourgeois cinematic genre, the family melodrama, into a platform for social investigation. Solas has made a cinematic political tract that simultaneously offers an inquiry into the strategies of our identification and sympathy for cinematic characters, making these novelistic creations a vehicle for political understanding.

As Lucia abundantly shows, the Cuban revolutionary cinema is a profoundly analytical form; accustomed to the demonizing of all Cuban cultural products as "propaganda, American audiences are frequently surprised at how critical of revolutionary hypocrisy the great Cuban films of the 1960's are, and how subtly they interrogate the nexus of personal and political engagement. Deeply influenced by the methods and the goals of documentary cinema, Lucia and other `60's Cuban films recruit documentary techniques to reduce the space between "the cinema" and the lived experiences of its Cuban audiences. In the third section of Lucia, the documentary mode becomes dominant, insisting on the material and physical truthfulness of the revolutionary understanding of class struggle.

Lucia joins Memories of Underdevelopment, Hour of the Furnaces, and the Battle of Algiers in setting out the terms of a what was coming to be known as "Third Cinema," a cinema that spoke to and for the anti-colonial, anti-capitalist, revolutionary spirit rising in what was known patronizingly (then and now) as "the developing world." These films, in turn, spawned cinematic movements in Brazil, Africa and elsewhere which transformed cinema into a medium in which "entertainment" became politicized, as audiences saw images of postcoloniality, sometimes un ironic and fervent, as in Gilo Pontecorvo's magnificent Battle of Algiers, sometimes sly and metaphorical, as in Nelson Pereira Dos Santos' How Tasty Was My Little Frenchman. American paranoia over Cuban cultural products haunted the Cuban cinema from the first. Although an award-winner on the international film festival circuit, Lucia, first released in 1968, wasn't screened in the US until 1974. (Indeed, an earlier attempt to show a group of Cuban films was summarily terminated by U.S. authorities, who stopped a screening of Lucia in mid-reel.) And the film never received the U.S. distribution of more acceptable art house fare. If it had, it is tempting to speculate on the effect it might have had on American feminism. Might it have helped to extract that feminism from its narrow, white, middle-class focus on personal liberation, and helped to make feminism a nodal point for a reformation of American society across classes and races? The Cuban revolutionary experiment will shortly, after the passing of its patron saint Castro from the scene, be put to its harshest test; it is entirely possible that Cuba will revert to its former status as a colonial vassal state, an ersatz `tropical getaway' destination subsisting on a commodified leisure and tourism economy, with American-owned casinos and locally owned poverty. If that happens, we will have only the celluloid memories of a remarkable time when Cuban artists like Humberto Solas spoke the language of social change for the world to see and hear.

— Kevin Hagopian, Penn State University

For additional information, contact the Writers Institute at 518-442-5620 or online at https://www.albany.edu/writers-inst.

Lucia

Lucia