FILM NOTES

FILM NOTES INDEX

NYS WRITERS INSTITUTE

HOME PAGE

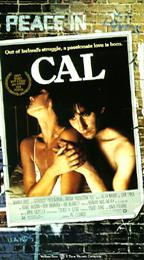

(Irish, 1984, 102 minutes, color, 16 mm)

Directed by Pat O'Connor

Cast:

Helen Mirren . . . . . . . . . . Marcella Morton

John Lynch . . . . . . . . . . Cal McCluskie

Donal McCann . . . . . . . . . . Shamie

John Kavanagh . . . . . . . . . . Skeffington

Ray McAnally . . . . . . . . . . Cyril Dunlop

The

following film notes were prepared for the New York State Writers

Institute by Kevin Jack Hagopian, Senior Lecturer in Media Studies

at Pennsylvania State University:

19 year-old "Cal McCluskie," a Catholic youth, (played by John Lynch) lives with his father in a Protestant neighborhood in a gray, despairing town in Northern Ireland where the Catholic-Protestant conflict is a fact as sure as the rain. A despairing quiet looms over the graffiti-spattered town, where violence threatens like a summer storm in the distance. Cal is a lesser IRA man, trying to undo his past. He and his father, "Shamie" (Donal McCann) had worked together at a slaughterhouse; now, that occupation reminds Cal too much of the blood that often runs in the streets. But the IRA is a close-knit, fearful fraternity, and membership, Cal is finding out, is for a lifetime, like it or not. As Cal’s relationship with "Marcella," (Helen Mirren), a policeman’s widow, grows emotionally more profound, it grows increasingly more complicated politically and morally. Cal’s fight to get closer to Marcella is frustrated by his own awful secret, and by the structures of authority in the town, both legal and illicit, which constantly force the two apart. Cal and Marcella hope to find a quiet place, a place apart from the violence and distrust around them. It is a vain hope.

Like ODD MAN OUT, one of its most important spiritual progenitors, CAL begins with an act of violence in support of the IRA. Initially, CAL seems to reject ODD MAN OUT’s existential rage against a cruel fate, offering reconciliation at the most human level. But as characters’ options narrow, the story moves toward an ending as foreordained as ODD MAN OUT’s suicidal shootout.

CAL is one in a small lineage of distinguished films that have dealt with the IRA and with the Troubles. ODD MAN OUT is among them, and so is THE INFORMER, and little-seen films such as Tony Luraschi’s THE OUTSIDER, Neil Jordan’s ANGEL (DANNY BOY) and George Schaefer’s television movie THE WAR OF THE CHILDREN. The best of these have chosen to find meaning not in the byzantine political concerns of the moment and the shifting constellation of the IRA and its splinter groups, but in the timelessness of Ireland’s agony. To make the rest of us share this agony, director Pat O’Connor seeks a common denominator that refuses to recognize the "rightness" of either the Catholic or the Protestant positions, so corrupted by bloodshed and intolerance has each become. Cal is torn in half by his loyalties, but they are loyalties expressed in human, not political terms. There is the widow, Marcella, to whom he knows he owes the truth, and his father, to whom he owes his love.

For producer David Puttnam, CAL was meant to follow his earlier THE DUELLISTS, MIDNIGHT EXPRESS, CHARIOTS OF FIRE and THE KILLING FIELDS. In these films, Puttnam reintroduced the tradition of ‘the quality film’ to U.K. and international cinema. New talents, risky themes, vivid direction, and tight budgets generated films both critically acclaimed and often economically successful. CAL exemplifies the Puttnam formula. Pat O’Connor’s direction has both pictorial elegance (he would go on to direct the exquisite A MONTH IN THE COUNTRY) and a naturalistic obsession with the details of life as it is lived in this cultural war zone. Dire Straits’ Mark Knopfler contributes an ethereal, introspective score that deftly stitches in Albert King’s blues anthem "Born Under a Bad Sign" as a voice for the often inarticulate Cal. CAL’s performances are perfectly keyed to the austere story. Helen Mirren’s Marcella is a heavily-layered character, a woman emerging from inside herself in a portrayal which won her the Best Actress Award at the 1984 Cannes Film Festival. John Lynch’s Cal is thin, shaggy, even bedraggled, the image, as one critic put it, of a "young Pete Townshend." Beneath the vague and affectless exterior, however, beats a deeply feeling, tortured heart.

CAL’s disrespect for both the Catholic and the Protestant "solutions" to Northern Ireland’s hemorrhage of violence and anger was seen by some critics as a ducking of responsibility; these critics pointed to the filmmakers’ disclaimer that CAL is a "love story that happens to be set in Northern Ireland." But CAL is no Romeo and Juliet. In this love story, the world is always with the lovers. And it is the very lack of love that drains the bitter Northern Ireland landscape of color and vision. Against that bleak backdrop, Cal and Marcella’s small, fitful gestures at romance bring a momentarily brighter palette to this gray hell.

— Kevin Hagopian, Penn State University

For additional information, contact the Writers Institute at 518-442-5620 or online at https://www.albany.edu/writers-inst.

CAL

CAL