![]()

Passing From Light Into Dark

John F. McClymer

Part 1 | Part 2 | Historiographical Essay

"Passing

from dark into light": The career of Warner Oland

"Old

San Francisco" reprised many of the themes of "Birth of a Nation." [Available

online at the University of New Orleans.] In it the villain is Silas

Lynch, a mulatto and close associate of Radical Republican Congressman Austin

Stoneman (modelled upon Thaddeus Stevens). Stoneman seeks racial equality, a position

even fellow Radical, Senator Charles Sumner, thinks extreme. But Stoneman is implacable

and sends Lynch to South Carolina to enforce his radical measures. A title describes

Lynch as "a traitor to his white patron and a greater

traitor to his own people, whom he plans to lead by an evil way to build himself

a throne of vaulting power." Lynch persuades local blacks to refuse to work for

whites. He uses his black troops to force whites to do his bidding. He misuses

Freedman's Bureau funds to support idle blacks whom he then enrolls as voters.

All of this is bad enough, but his worst crime is his desire for Congressman Stoneman's

daughter Elsie. She is in love with the scion of an old South Carolina family,

Ben Cameron. Lynch spies them kissing in a garden. But Elsie and Ben realize they

cannot marry since she must be loyal to her father and he must defend the white

South from Radical Reconstruction. Lynch

wins the lieutenant governorship in an election in which whites are barred from

voting. The new legislature, dominated by blacks, passes, among other outrages,

a bill permitting racial intermarriage. As Lynch's abuse of power grows, Ben Cameron

decides to take action. He forms the Ku Klux Klan which a title calls "the organization that saved the South from the anarchy of black

rule, but not without the shedding of more blood than at Gettysburg." The greatest

danger is to white womanhood, embodied first in Cameron's sister, Flora, who dies

in a fall while fleeing the amorous attentions of a black militia officer, and

then in Elsie Stoneman to whom Lynch proposes. As Delores Vasquez would do a decade

later, she recoils and threatens him with a "horsewhipping for his insolence."

"Lynch, drunk with wine and power, orders his henchmen to hurry preparations for

a forced marriage." Elsie faints into Lynch's arms. Her father arrives, and Lynch

informs him of his plans: "I want to marry a white woman � The lady I want to

marry is your daughter." Stoneham, despite his own earlier dalliance with a black

servant, is furious. But Lynch has the upper hand. In

both films, the villain sought wealth, social acceptance, power, and the hand

of the daughter of a prominent family � despite being barred from all of these

by his race. In both the villain mastered all of the outward forms of white society

but inwardly remained true to his racial origins. In both a stalwart young hero

thwarted his diabolical schemes and then married the heroine. This signalled,

in both films, the start of a new era, one based upon racial purity which is thematized

in both by the unsuccessful attempted rape of the heroine. Her honor saved, society

can renew itself. Not

only do the two films emphasize the same themes, but in both the villain was played

by a white actor. In "Birth of a Nation" it was George

Siegmann who, in 1927, would play the cruel slaveholder Simon Legree in "Uncle

Tom's Cabin." In another parallel both movies inspired vigorous protests by offended

African and Asian Americans. The premiere of "Old San Francisco" led to a riot

in that city. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP)

led a boycott of "Birth of a Nation." The

Klan of the 1920s would scarcely have endorsed "Old San Francisco" with its heralding

of the marriage of Delores Vasquez and Terrance O'Shaughnessy as the beginning

of a new era. For them true Americans were Protestant and of northern European

stock. This makes "Old San Francisco's" appropriation of plot devices and thematic

material from "Birth of a Nation" all the more revealing. In both films the hero

and heroine are kept apart by ethnic or sectional animosities. These are shown

to be less essential than race. White Northerners and Southerners can reunite,

Irish and Spanish-Americans can unite, because race is enduring while sectional

and ethnic antagonisms are not. "Imagine a person,

tall, lean and feline, high-shouldered, with a brow like Shakespeare and a face

like Satan, a close-shaven skull, and long, magnetic eyes of the true cat-green.

Invest him with all the cruel cunning of an entire Eastern race, accumulated in

one giant intellect, with all the resources of science past and present, with

all the resources, if you will, of a wealthy government -- which, however, already

has denied all knowledge of his existence. Imagine that awful being, and you have

a mental picture of Dr. Fu-Manchu, the yellow peril incarnate in one man." --

Nayland Smith to Dr. Petrie, The Insidious Dr. Fu-Manchu : Being a Somewhat

Detailed Account of the Amazing Adventures of Nayland Smith in His Trailing of

the Sinister Chinaman (New York, 1913), Chapter 2. Rohmer

offered several accounts of how he came up with the idea for Fu Manchu. They differ

in several details. However, the broad outline seems indisputable. Rohmer was

a young reporter with ambitions of becoming a writer of fiction. He accepted an

assignment in the Limehouse section of London to investigate the criminal activities

of a "Mr. King," a Chinese master criminal who supposedly controlled the gambling

and opium in the district. Rohmer learned little beyond second-hand tales. Then,

late one night, as he was about to head home, a limosine pulled into a narrow

alley: The

car pulled up less than ten yards from where I stood. A smart chauffeur switched

on the inside light, jumped out and opened the door for his passengers. I saw

a tall and very dignified man alight, Chinese, but different from any Chinese

I had ever met. He wore a long, black topcoat and a queer astrakhan cap. He strode

into the house. He was followed by an Arab girl, or she may have been an Egyptian.

She reminded me of an Edmund Dulac illustration for the Arabian Nights. The chauffer

closed the car door, jumped to his seat, and backed out the way he had come in.

The headlights faded in the mist . . . and Dr. Fu Manchu was born! If

the tall Chinese was the elusive "Mr. King" or someone else, I cannot pretend

to say; but that he was a man of power and enormous authority I never doubted.

As I walked on through the fog I imagined that inside that cheap-looking dwelling,

unknown to all but a chosen few, unvisited by the police, were luxurious apartments,

Orientally furnished, cushioned and perfumed. I saw a spot of Eastern magnificence,

a jewel in the grimy casket of Limehouse. That very night, alone in my room, I

searched through memories of the East, finding a pedigree for the beautiful girl

I had seen through the fog. And she became Karamaneh (an Arabic word meaning a

confidential slave), an unwilling instrument of the Chinese doctor. Little

by little, that night and on many more nights, I built up Dr. Fu Manchu, until

at last I could both see and hear him. His knowledge of science surpassed that

of any scientist in the Western world. He controlled every secret society in the

East. I seemed to hear a sibilant voice saying, "It is your belief that you have

made me; it is mine that I shall live when you are smoke." -- Sax Rohmer, "How

Fu Manchu Was Born," This Week, September 29, 1957. Fu

Manchu strongly resembled Arthur Conan Doyle's Professor Moriarity, the evil genius

of crime who was Sherlock Holmes' most formidable antagonist. Both had enjoyed

advanced educations in Europe's finest universities; both employed beautiful women

in their nefarious schemes; both had powerful intellects that enabled them to

outwit the authorities. What

made Rohmer's version of the criminal mastermind so enduringly popular was his

use of the "yellow peril" motif. Fu Manchu had learned western languages � his

English was flawless; he had mastered western sciences, especially medicine. Yet,

like Chris Buckwell in "Old San Francisco," he remained an implacable enemy of

western values. In another account of the creation of the character, Rohmer wrote

that Fu Manchu had become so real to him that he and the insidious doctor engaged

in a dialogue: He

was so real that I answered him. One listening must have assumed that I, sitting

alone in my room with the grey light of dawn just beginning to peep through the

curtains, had become demented. It was not so. I had created something, and it

was to the Mandarin Fu Manchu that I replied: "It will be a square fight, but

a fight to the finish, Dr. Fu Manchu." "A

member of my family," he answered, "a mandarin of my rank, never breaks his word.

For myself I ask nothing. I hold the key which unlocks the hearts of those who

belong to every secret society in the East, including the Thugs. I command every

Tong in China. My knowledge of medicine exceeds that of any doctor in the Western

world. I shall restore the lost glories of China -- my China. When your Western

civilization, as you are pleased to term it, has exterminated itself, when from

the air you have bombed to destruction your palaces and your cathedrals, when

in your blindness you have permitted machines to obliterate humanity, I shall

arise. I shall survey the smoking ashes which once were England, the ruins that

were France, the red dust of Germany, the distant fire that was the United States.

Then I shall laugh. My hour at last! Your Nayland Smith, your Scotland Yard, your

Dr. Petrie, yourself, all will be blotted out. But China -- my China -- its willing

millions awaiting my word -- China, then, will come into her own. The dusk of

the West will have fallen: the dawn of the East will have come." -- Sax Rohmer,

"Meet Dr. Fu Manchu," from MEET THE DETECTIVE, edited by Cecil Madden,

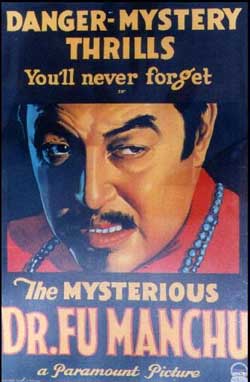

published by the Telegraph Press, New York, 1935. Oland made three

Fu Manchu films, starting with "The Mysterious Dr. Fu Manchu" in 1929. In each

his evil scheme is foiled by Nayland Smith, purportedly a nephew of Sherlock Holmes,

and Smith's doctor friend, Jack Petrie. [For a detailed plot summary of the first,

enlivened with sound clips, go to The Missing Link

site.] Oland then found a new Oriental character to play, Charlie Chan. According

to Associated Press reporter Patrick Williams in a column, no longer available

online, celebrating the seventy-fifth anniversary of the first Chan mystery, In 1924, Earl Derr Biggers,

a Boston playwright and author, was contemplating a mystery set in tropical Honolulu,

where he had vacationed four years earlier. Leafing through a stack of Honolulu

newspapers to refresh his memory, the writer came across a small story about Apana

[a real Chinese detective] and an opium arrest. Immediately, Biggers hit on the

idea of a good-guy Chinese character for his mystery. "Sinister

and wicked Chinese were old stuff in mystery stories, but an amiable Chinese acting

on the side of law and order had never been used up to that time," Bigger recounted

in a 1931 Honolulu newspaper article. Like

Fu, Charlie was highly intelligent. He was not, however, an enemy of western values

even though he remained faithful to Chinese traditions and was given to citing

ersatz Chinese aphorisms. When Oland unexpectedly died in 1938 just before the

shooting of what was to have been his seventeenth Chan film, Twentieth-Century

Fox turned it into "Mr. Moto's Gamble" with another European actor, Peter Lorre,

as Chan's Japanese counterpart. Oland's

performance as Chris Buckwell so outraged Chinese Americans that those in San

Francisco rioted at the premiere. Later, Chinese students at Columbia University

boycotted an appearance by Sax Rohmer because they found the "yellow peril" stereotype

he exploited in creating Fu Manchu so hateful. But, in 1935, Oland made a triumphal

tour of China where he was surrounded by thousands of fans of Charlie Chan. Many

refused to believe that Oland was not himself Chinese. [For more on Chan as the

"good" Oriental, click here.] Passing As A Cultural

Trope Hollywood,

as we have seen, routinely cast whites as Chinese and Japanese. Boris Karloff,

pictured at right in a publicity still for "The Mask of Fu

Manchu," replaced Warner Oland in the title role. Myna Loy, today remembered for

playing Nora Charles opposite William Powell in "The Thin Man" series, played

Fu's daughter � not Anna May Wong.

In fact, Wong lost so many roles to Loy that she left Hollywood for several years

and pursued her career in Europe. Japanese-American Sessue Hayakawa fared little

better. [17] Peter Lorre

played Mr. Moto.

More notably, perhaps, the 1937 production of Pearl Buck's best-selling novel

about the resilency of Chinese peasants, "The Good Earth," starred

Paul Muni, an Austrian Jew who got his acting start on New York's Yiddish stage,

as Wang Lung and Austrian-born Louise Rainer as O-Lan, a role for which Rainer

won an Oscar. [18] "Passing," so long as

it meant going from "light into dark," was a commonplace of American popular culture.

It was more. It was virtually a requirement. With the notable exceptions of Anna

May Wong and Sessue Hayakawa, Asians were not cast as Asians. Whether the scripts

called for villains or "good guys," "dragon ladies" or faithful wives, whites

played the parts. Wong and Hayakawa did get some supporting roles. Similarly,

a few blacks also broke into movies made by the major studios. Noble Johnson,

who created his own production company in the early 1920s to make films for African

American audiences, played supporting roles in "The Ten Commandments" and other

silent films. He continued his career in the sound era. He was the native chief

in "King Kong" (1932) and, far more remarkably, the Tartan Ivan

in "The Most Dangerous Game," which was shot at the same time. This is the first

instance, so far as I have been able to determine, of any black actor playing

a white in a movie. In 1922 Allen "Farina" Hoskins

appeared in the second "Our Gang" short. In 1927 James Lowe starred as Uncle Tom.

And Stephin Fetchit launched his career in the 1927 silent "In Old Kentucky."

For the most part, however, African Americans got work only in crowd scenes or

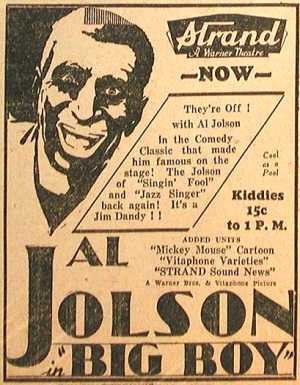

playing servants. In

"Big Boy" Gus's family had worked for the Bedfords for generations. Indeed back

in 1870 his grandfather had rescued John Bedford's fiance� from the evil John

Bagby who had shot Bedford and kipnapped her. What is more, he had dragged Bagby

back to justice at the end of a rope. This meant, Mrs. Bedford reminds her children,

that Gus will ride their prize racehorse "Big Boy" in the Derby: "We Bedfords

must never forget what our darkies remember." Nonetheless, her son contrives to

have Gus fired so that another jockey can ride "Big Boy" and throw the Derby.

Gus learns of, and stops, this wicked scheme. He then rides "Big Boy" to victory. "Gus"

offers several clues to the popularity of blackface and of white performers in

Asian roles. Most obvious, perhaps, is the reinforcement of certain classic stereotypes

-- the loyal "darky," the aristocratic white family that takes care of its faithful

servants. "Gus" also allowed Jolson to do a type of humor

otherwise out of bounds. For example, when "Gus" learns that Mrs. Bedford's son

got him fired because he was being blackmailed over a bad check he had written,

"Gus" immediately determines to retrieve it. Just then he sees Dolly Graham, one

of the gang of blackmailers, slip it down her dress. "Gus" arranges to have the

lights turned off in the restaurant where he is now working. There is much shrieking

and clamor during the darkness. Dolly calls out: "Coley [another blackmailer],

somebody is after the check!" Later, "Gus's" friend Joe asks: "Did you get the check, Gus?" At

the same time, because Jolson is white, "Gus" says and does things that no African

American could. Putting his hands inside a white woman's dress is the most flagrant

case in point. But, it also was only possible to portray the adventures of "Gus's"

grandfather because the actor beating up the white villain was himself white.

So too with this exchange between "Gus" and the blackmailers. Gus approaches their

table. They are arguing heatedly. "Gus" chides: "Hey,

hey, where do you think you are? You can't argue like this in a public place.

This ain't your home, ya know!" The

villain tries to punch "Gus" but misses. Then the lights go out. And the Jolson

character attempts to grab the check. "Gus"

is, despite surface similarities, the direct opposite of the character made famous

by Stephin Fetchit. "Gus" is quick-witted, quick moving, fearless, resourceful.

Stephin Fetchit is slow of wit and of foot, frightened of his own shadow, and

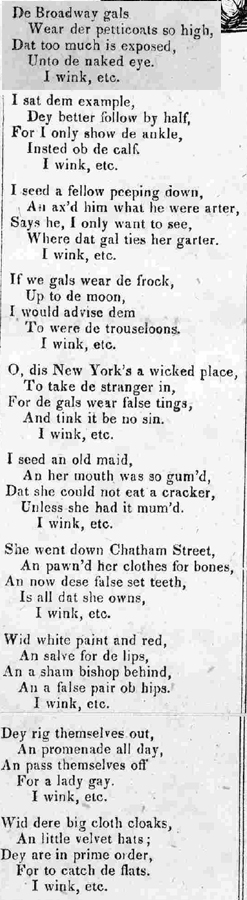

always at a loss as to what to do. She

tried to show "de Broadway gals" a good example by only showing "de ankle, insted

ob de calf." But the "Broadway gals" wear "de frock up to de moon," exposing "too

much . . . unto de naked eye." New York, she lamented, was "a wicked place . .

. for de gals wear false things, and tink it be no sin." They used "white paint

and red, and salve for de lips, an a sham bishop behind, an a false pair ob hips."

Then they promenaded "all day." For whom did they put on this show? Watching,

peeping actually, is "a fellow" whose object is "to see where dat gal ties her

garter." In

minstrelsy performers and audiences were accomplices. Performers pretended to

be black � this holds for African-American ministrels as well who had to use cork

makeup and conform to the stereotypes established by whites � and the audiences

pretended to believe they were black. Mutual pretense created an imaginary space

in which blacks were simultaneously stupid and intelligent, crude and tender,

ignorant and sharp-eyed observers of the white world. It was permissable for "Dinah"

to criticize white "gals" who "wear der petticoats so high, that too much is exposed

unto de naked eye" in the bluntest terms, provided she did so in a comic dialect.

"Gus" could paw the white Dolly. Blackface celebrates crude expressions and gestures.

In the 1924 Norton

Company Minstrel Show "saluting" St. Patrick's Day, use of blackface permitted

Swedish-Americans, Yankees, and other Norton employees to insult Worcester's Irish

with unbridled enthusiam. It was the white skin beneath the cork which permitted

such "uppitty" behavior. "Showboat"

made use of a fascinating variation. Helen Morgan, a white singer and actress,

played the mulatto Julie without the use of makeup. This was acceptable because

Julie was "passing." She had to look white. The only hint the audience is given

of her racial origins is the fact that she taught Magnolia a song, "Can't Help

Lovin' That Man Of Mine," which supposedly only African Americans knew. But, in

asking white audiences to identify with Julie and to affirm her love for Bill

and to thereby reject American racial boundaries, the show itself carefully observed

them. The woman kissing Bill was a white pretending to be mulatto. Today, the

estate of Oscar Hammerstein II refuses to permit performances of "Showboat" in

which whites portray black characters. Not so in the original, nor in the first

film version in which Morgan recreated her role, nor in the 1950s remake in which

Ava Gardner played Julie. "Birth

of a Nation" provides another example. Here too performers and audiences were

complicit. The villainous Silas Lynch lusted after the virginal Elsie Stoneman,

who fainted in his arms in sheer terror when he announced his intention to force

her to marry him. It was essential to the whole mythology of the Klu Klux Klan

which the film celebrated that he almost succeed in forcing himself upon her.

Ben Cameron, the founder of the Klan in the movie, must save her and, by extension,

white womanhood, from the most terrible danger. For the same reason Lynch must

menace her because he has black blood. But George Siegmann, the actor playing

Lynch, could hold and caress Lillian Gish without violating racial taboos only

because he was white. So too with Warner Oland in "Old San Francisco" and "The

Mysterious Dr. Fu Manchu." In both films he had a beautiful white woman in his

clutches. His capacity for evil derived from his "Oriental blood"; so did Fu Manchu's

daughter's sadistic impulses in "The Mask of Fu Manchu." But it was the white

Myrna Loy to whom her white victims grovelled. Similarly, Charlie Chan and Mr. Moto could "outfox" not only the

wiliest white criminals but also the most clever white police because underneath

their Oriental cunning was white skin. There

was no Asian equivalent to black minstrelsy. Swedish women gymnasts and performers

in parochial school productions of "The Mikado" aside, few immigrants from Europe

or their children could affirm their own American identity by assuming a Chinese

or Japanese persona. But understanding the rules of "passing" was an

important component of acculturation. These were, as I have tried to demonstrate,

complex. And, as they applied to ethnic groups of European origins, they were

in flux. Exploring this was at the heart of the Marx Brothers' comedy. [21] Groucho

played Yankees who had names like Otis B. Driftwood; brother Chico's characters

were Italian with names like Fiorello. Harpo had no stable ethnic identity. He

was pure id, appetite unregulated by superego. He neither needed nor used language.

He simply grabbed whatever he wanted, usually sex and food.

In "A Night at the Opera" there are several scenes

about Harpo and eating, each a virtuoso turn. Groucho and Chico, on the other

hand, were masters of language which they turned and twisted to suit their own

purposes. In "A Night at the Opera" they negotiate a contract for a promising

tenor. They take turns objecting to each clause. They resolve these disputes by

tearing off strips of the contract until each is left holding only a small fragment

of paper. What is this last clause, Chico demands to know. Oh, Groucho responds,

that is just the sanity clause. There was one in every contract. Chico shoots

him a "You can't put that over on me" look and says: "Everybody knows there ain't

no Santy Claus." [To hear the scene in RealAudio, click on the image.] Together

the brothers turned every established WASP institution and practice � from the

opera to horse racing to big game hunting to college life to diplomacy � to shambles.

Here

again the trope is "passing." Like Cantor in "Whoopee!" the brothers do a number

of jokes to remind the audience of their Jewish background. In "Animal Crackers,"

for example, they form a barbershop quartet, "from the House of David," to sing

"Old Folks at Home." Yet Groucho's character is Captain Spaulding, "the African

explorer." And Chico plays an Italian musician. Ethnic

Cultures and Mass Culture The

decade of the 1920s was one of ongoing cultural warfare centered around issues

of race, ethnicity, and religion. Questions of who was a "real" American, of the

place of Catholics in American public life, of the place of Jews, of immigrants

from central and eastern Europe dominated politics. Advocates of "100% Americanism"

won important early victories, such as Prohibition and immigration restriction.

But "wets" and Catholics and blue-collar ethnics and their families found a political

home inside the Democratic Party which would enable them to recoup some of their

losses in the 1930s and 1940s. [This is the organizing theme of the 1920s section of

the American History and Culture on the Web project I co-direct.] These

issues dominated much of the science of the day as the widespread acceptance of

eugenics indicates. More than thirty states adopted laws banning interracial marriage

and almost as many had programs of involuntary sterilization for those deemed

"a burden upon the rest of us." These same issues dominated

much of the debate over educational policy as school systems across the country

adopted standardized tests, often developed in cooperation with leading eugenicists,

and tracking schemes devised to give special attention to "gifted and talented"

students who, not coincidentally, superintendents and principals presumed would

include few Italians, Poles, or Greeks. Advertising,

as Roland Marchand and others have shown, promoted and reflected notions of "Anglo-conformity."

From ads for skin cremes that

would enable women to stay young to those for automobiles which promised mothers

would no longer be "Marooned!" at home

with young children one found white faces with regular features.

There were no Roman noses; no one with olive skin. When ads used names, as they

often did, they were Yankee names. [22]

[For an especially egregious case in point, Lifebuoy's use of eugenics themes

in its ads of the 1920s, click here.]

It was in the emerging

mass culture that European immigrants and their children had an equal say. Mass

culture in the 1920s, as Frank Couvares noted in the case of Hollywood, was a

m�lange of ethnic and racial voices and faces. [23]

Compared to what Henry May called the "citadels of culture," such as faculty positions

at elite universities and editorships at prestigeous journals

and publishing houses, members of European ethnic groups had far greater access

to mass media. [24] They wrote

many of the popular songs; they produced the movies; they starred on the vaudeville

circuits and the legitimate stage. They wrote, produced, and starred in radio

programs. In contrast, while second-generation immigrants did go to college in

greater numbers during the 1920s, faculty and administrators, especially in elite

institutions, remained overwhelmingly WASP. So too with editors and publishers.

More second-generation immigrants were writing novels, short stories, poetry,

and non-fiction in English. But few gained a wide readership. The shelves of libraries

and bookstores were filled with WASP names. The

person going in to buy sheet music in the 1920s, on the other hand, would see

the faces of Al Jolson, Bert Williams, and Fanny Brice on

the covers. If that person continued down Main Street past the new movie "palace,"

he or she would pass posters advertising current and future shows. Pictures of

Rudolph Valentino in "Son of the Sheik" or Ramon Novarro in "Ben-Hur" were part

of everyday experience. If that person then went home and turned on the radio,

Eddie Cantor or Jack Benny might be on. What

European ethnics used their access to the mass culture to say was often flippant,

often funny, often mawkish. It was not trivial. They proclaimed that Catholics

and Jews and "Hunkies" and others from southern and eastern Europe were the equals

of self-styled "real" Americans. As the examples from Worcester show, ethnic communities

eagerly embraced key elements of this mass culture and used them to similar but

not identical ends. For they were engaged in battling each other quite as much

as resisting discrimination at the hands of Yankees. This

openness to white ethnics, to Catholics and Jews, in the mass culture rested upon

strict racial boundaries. If our hypothetical stroller down Main Street had caught

Duke Ellington and his Orchestra on the radio, broadcasting live from the Cotton Club,

the first voice would belong to Ellington's white manager, Irving Mills, who would

introduce Ellington as "Dukie," "the greatest living master of jungle music."

The club itself took its name and decor from romaniticized notions of the Old

South. The waitstaff were all dark-skinned; the chorus line all light-skinned.

The customers were all white. It was during his Cotton Club engagement that Ellington

wrote "Black and

Tan Fantasy" with its quotation of Chopin's Funeral March. Historians

whose sympathies normally lie with those struggling to gain

a foothold in American society become uncomfortable [25]

because European ethnics made their claims for equality within a racial hierarchy

in which African and Asian Americans were firmly put, and held, in their places.

This makes them collaborators in America's centuries-old history of racial exploitation.

Even when they took a stand against racism, as with "Showboat," they still observed

its protocols. Or they unreflectively made use of racial stereotypes, as with

the original lyrics of Irving Berlin's "Puttin' On The Ritz" which poked fun at

African-American "Lulu Belles and their swell beaux" "spending their last two

bits, puttin' on the Ritz." Acculturation,

however, is about fitting in, finding a niche. Immigrants and their children lived

in a society in which racial and ethnic stereotypes helped determine their life

chances. It is hardly surprising that they seized their opportunities to further

their own groups' standing without overmuch concern with what happened to others.

Part

1 | Part 2 | Historiographical

Essay

"Did I get the check? Say, I'm an ol' check getter. When I set

out to get me a check I . . . I . . . Oooooh, Mr. Joe, what must that woman think

of me?" "Gus" holds up a piece of lingerie.

"Where did you come from?"

"A reindeer

brought me!"

"Are you looking for trouble?"

"Yeah!

Do ya got any?"

~ End ~

Comments

| JMMH Contents