![]()

Historiographical Discussion:

If the Irish

Weren't Becoming White, What Were They Doing All those Years?

John

F. McClymer

"Passing from Light into Dark,"

I hope, will serve to deepen and complicate the ongoing scholarly conversation

about race, ethnicity, acculturation, and their interrelationships. This conversation

currently turns upon varying notions of cultural "construction." Ethnic identities

are "inventions." [1] Implicit

in most of scholarly treatments, and explicit in some, is the assumption that

the "invented" ethnic identity served some utilitarian purpose. [2]

Indeed, it is virtually impossible to think of a purpose for which scholars have

not found a corresponding ethnic "strategy." Ethnic strategies eased problems

of locating housing, finding employment, promoting the growth of a business class.

Beyond such practical uses, the creation of ethnic identities helped groups and

individuals find their way into the larger American culture, moderate intergenerational

conflict, and seek religious solace. [3] Race

too is "constructed" and "strategic." This part of the conversation differs, however,

in focusing less upon how African Americans seek to create a racial identity

than upon the ways whites attribute racial characteristics to them. [4]

The conversations over ethnic and racial identities come together over the issue

of how various ethnic groups "became" white. If "blackness" was "constructed,"

does it not follow that "whiteness" too was an invention? Symmetry is a tacit

expectation of theory. David Roediger and Noel Ignatiev raised this question of

how groups "became" white in the early 1990s followed by Matthew Frye Jacobson

late in the decade. [5] It is

no exaggeration that this notion swept the scholarly community by storm. [6]

So did Eric Lott's related thesis, that the white working class achieved acceptance

in the antebellum period via minstrelsy. [7]

This "whiteness" literature reached an apotheosis of sorts in Matthew Pratt Guterl's

The Color of Race in America, 1900-1940 in which he argues that a "bi-racial"

polarization of American society became the ruling idea during the 1920s. [8] The

life of the law, Oliver Wendell Holmes famously observed, has been experience,

not logic. How much more is this true of American racial and ethnic relations?

In the law there are carefully drafted opinions which adhere to the formal demands

of logic. No one can accuse ethnic or racial "constructions" of following any

sort of logic. Yet "whiteness" studies rest upon a mountain of theory, with the

accompany assumption that there is some logic to human activities, and

a modicum of fact. It is impossible to review this entire literature in detail.

Nor, given Peter Kolchin's recent essay, is there any necessity to do so. [9]

Instead I will examine two widely accepted claims advanced in this literature.

One is the founding assertion, that the Irish "became" white either during the

1850s or some time thereafter. Upon what evidence does this rest? There

was in the 1850s a powerful political movement animated by a profound distrust

of, even fear of, the Irish. Did the Know-Nothings claim that the Irish were not

white? If they had, their political program would have made no sense. Why lengthen

the period an immigrant must reside in the U.S. before becoming naturalized if

the Irish were not white? Only whites were eligible for naturalization. Many

states prohibited non-whites from voting, from serving on juries, and from testifying

in court against a white man. In California these laws applied to the Chinese,

even though the state constitution specifically used the word "black" in imposing

these restrictions. Why was there never any attempt, by any group, to use

these restrictions against the Irish? Many, especially in the North, despised

the Irish. They saw them as ignorant, superstitious, priest-ridden, alcoholic.

They, correctly, saw the Irish as the enemy of reform, whether that meant temperance

or free soil. The Irish opposed the reading of the Bible in the public schools.

Some Yankees feared the Irish had secret caches of weapons and were only awaiting

word from the Pope before rising up and trying to overthrow the republic. Know-Nothing

editorials are replete with these accusations. [Worcester]

Daily Evening Journal, Friday, Dec. 8, 1854 In

speaking upon this subject, it is useless to recount the enormities committed

against the moral feelings of the whole city, during the first year of the present

mayor's administration, when murders were perpetuated with impunity, and known

violators of law permitted to go unpunished and unrebuked, provided their sinning

was on the side of rum and intemperance. From the moment that he refused to appoint

a Marshal, for whom more than a thousand citizens petitioned, vice and immorality

held a jubilee, for they saw that the executive power of this city was their friend

and ally, and rum shops sprung up at every corner of the street, drunkards staggered

in every alley, while prostitution reared its brothels at every thoroughfare leading

to us, and held carnival in the very heart of the city itself. Virtue was confronted

on the streets by known harlots, young men decoyed to houses of infamy in open

day, and beneath the very shadow of the Mayor's office, the courtesan bargained

for the price of her embraces, and led her victims to a place of assignation.

Public opinion cried out against these outrages of decency, but the executive

power of the city was as dead to petitions, to remonstrances, and to cries of

help for redress, as it was destitute of those high principles of morality that

alone can adorn an official position. No descents, as are done in other cities,

was [sic] made upon known houses of ill fame, and the quiet of four suburban villages

was destroyed by their hellish orgies, while thieves made their dens the receptacles

of their stolen plunder, and vice, hideous, loathsome and revolting, revelled

in and disgraced our city. The people, at last, publicly rose against the Mayor,

pulpits exposed his heedlessness and disregard of the honor of the city, and he

retorted by accusing them of falsehood in their statements in regard to the amount

of crime among us. A change was made in the city marshal, Irishmen made constables

and appointed watchmen, and halycon days were once more to shine upon the city;

but the Scriptures were still true, and the "last (year) of that man was worse

than the first." The

Daily Evening Journal gave its readers a laundry list of reasons to hate

and despise the Irish. They perpetrated the murders; they set up the rum shops;

they were the drunkards staggering in the alleys; they were the harlots decoying

young (Yankee) men to houses of infamy. Worse, they were now the police! But,

where is the claim they were not white? [10]

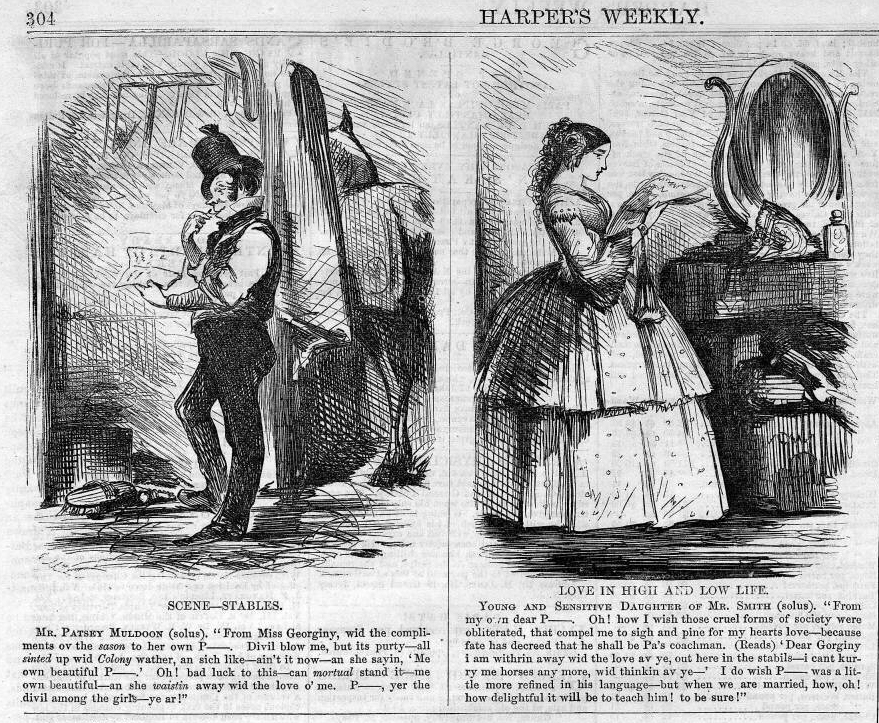

Know-Nothings by no means had the anti-Irish field to themselves. Consider this

cartoon from Harper's Weekly. [11]

Crime in the City. [editorial]

"Love in High and Low Life" made fun of "Mr. Patsey Muldoon" and the "young and sensitive" Miss Georgiana Smith in several ways. It parodies his brogue, his borderline literacy, and his serene self-esteem. And it mocks Georgiana's indignation at "those cruel forms of society" which decreed her love must "be Pa's coachman" and her naive belief that she would be able to refine him. Their marriage, the cartoon made plain, would be wildly inappropriate. What it does not do is suggest that it would violate the laws prohibiting miscegenation. Those laws did not apply to the Irish. This is not a minor point. "White" Americans, whatever that term turns out to mean, routinely used the law to discriminate against non-whites throughout the nineteenth century and well into the twentieth. The fact that the Irish faced no legal discrimination when it came to voting, holding office, serving on juries, applying for licenses, or owning real estate, even during periods of intense opposition to their presence, speaks volumes. The other claim I wish to examine is advanced by Guterl in The Color of Race in America, 1900-1940. He argues that, under the leadership of Madison Grant, Americans of Anglo-Saxon and Nordic stock adopted a program of "white world supremacy" which united everyone who looked "white," adopted English, and waved the flag. (p. 8) This new ideology of "Nordicism" supposedly included the Irish by the 1920s. This makes theoretical sense. If the Irish had attained at least a tenuous hold on "whiteness" in the 1850s, surely they had become full-fledged Nordics by the 1920s. Whatever its theoretical consistency, it is simply wrong as a statement of fact. The Irish and the Anglo-Saxon did not kiss and make up in the 1920s. Instead that decade, along with the 1850s, marked the high water mark of anti-Catholicism in American history. The second Ku Klux Klan, which did adopt the Nordic banner and which enrolled millions, promised to reclaim American public life from Catholics, Jews, and immigrants and their children generally. They found themselves vigorously opposed in city streets and in the Democratic Party by Irish-led coalitions. Al Smith carried the banner against the Klan. To describe the period after the passage of the Immigration Restriction Law of 1924 as one in which battles between and among groups of European extraction faded away is to ignore riots, Konvocations, the Smith vs. McAdo battle for the Democratic nomination in 1924, and the enormous ethnic upheavals that accompanied Smith's 1928 run for the presidency. In Worcester that election provoked a riot in which almost 20,000 out of a city population of less than 200,000 threw paving stones, bricks, and other missiles, and engaged in fist fights and general mayhem for several hours. A contemporary poem, distribed in mimeographed form on election day, read:

"Nonhistorians [among whiteness scholars]," Kolchin observes, "are particularly prone to deprive whiteness of historical context." Unfortunately, "inattention to context bedevils many of the historians as well." [13] This, he suggests, derives in part from their attention to cultural texts, like Madison Grant's The Passing of the Great Race, and their disinclination to explore events. Very little ever happens in this literature. Abstractions on the order of "subordination," "expropriation," and "oppression" supplant events. I am not contending that no one ever called any European immigrant a name indicating he was not white. In 1880 Carroll D. Wright, in his Report of the Massachusetts Bureau of the Statistics of Labor referred to the "Canadian French" as "the Chinese of the Eastern States." [14] Edward A. Ross, a leading sociologist of the Progressive Era, wrote in 1914 that "'The Slavs are immune to certain kinds of dirt. They can stand what would kill a white man.'" [15] It is not difficult to multiply examples. Surely they must provide some evidentiary base for claims advanced in "whiteness" studies about how European ethnic groups "became white? The fact is that they do not. Race permeated American idiom. "White" was complimentary, as in "That's white of you." Any reference to non-whites was amost always insulting, as in "work like a slave." When Carroll D. Wright called French Canadians "Chinese," he fully intended to insult them. They were, he wrote, "a horde of industrial invaders" who "cared nothing" for American institutions and whose best trait was their "docility." Yet, after holding a hearing at the Canadians' request, he concluded that "their ultimate assimilation" was but "a matter of time." Had he actually meant they were not white in a racial sense, he could never have come to such a view. The case with Ross is different. He did intend a racial meaning. He intended, in fact, precisely the sort of "Nordic" supremacy meaning Guterl misunderstands so completely. These were people, he wrote in the same article in The Century, who belonged in "wattled huts" at the "beginning of the last ice age." They were people "evolution had left behind." Further, Ross's view of Slavs had powerful political support. Former President Theodore Roosevelt wrote an admiring introduction when Ross's articles on "The Old World in the New" were published in book form. But the champions of Nordic supremacy never succeeded in restricting the meaning of "white" to themselves. On the other hand, they never held out the hand of fellowship to "Hunkies," "Dagoes," and others from southern and eastern Europe. "Nordic" had a specific racial meaning which Grant used to exclude lesser "breeds." The Irish were not Nordic. They were white. This was true in the 1850s. It was true in the 1920s. The fact that neither claim examined here stands up does not prove that there is no merit in the "whiteness" literature. It does suggest, as does Kolchin's review essay, that that literature is frequently based less on exhaustive research than upon expansive readings of texts and reverential citation of other works of other "whiteness" scholars. Conflating ethnic struggles to get ahead with a mythic quest for "whiteness" obscures the reality of the ethnic experiene. This takes us to the question posed in the title of this essay: What were the Irish, and other European immigrants, doing? In a word, they were jockeying. If, following the lead of Stanley Lieberson, we think of American society in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in terms of various groups standing on a series of queues leading to jobs, housing, and other needful and desirable things, we can describe their experience as jockeying for a better position. Charles W. Estus, Sr. and I have coined a more formal term, triangulation. [16] The task at hand for immigrant groups was to move up on the queues or, at worst, not lose ground. This meant paying close attention to Yankee preferences, since they controlled access to many of the jobs, owned much of the real estate, oversaw the hospitals, sat on the boards of community organizations, and held numerous other levers of power. It also meant paying close attention to the activities of competing groups. In Worcester in the 1880s and 1890s newly arrived Swedes succeeded in elbowing the already established Irish aside in the blue-collar labor market. [17] In 1907, when Sweden's Prince Wilhelm, Duke of Soderman and second son of Crown Prince Oscar Gustav, visited Worcester, the city's Swedes turned out in force to welcome him. Their spokesman was J.O. Emanuel Trotz, superintendent of the South Works of the American Steel and Wire Company, Worcester's largest employer. Swedes, he said in his welcome

On the other hand, Swedes, to their immense chagrin, failed to create a national "day" for themselves for decades, largely because they insisted upon presenting themselves as a "colonizing" rather than an "immigrant" people who thus deserved to rank with the English. "Forefathers' Day," their attempt to celebrate the founding of New Sweden fell flat. Meanwhile, the Irish had St. Patrick's Day, the French Canadians had both Mardi Gras and St. Jean Baptiste Day, the English had St. George's Day, and so on. The Irish finally goaded the Swedes into agreeing upon a "day" based upon an Irish, ethnic model, "Midsommar." This happened because of the Irish success in getting the Massachusetts legislature to make Columbus Day a state holiday. This infuriated Swedes on two counts. One was that it gave official recognition of Columbus and not to Leif Erikson. The other was that the Irish had more than a "day." They had an official state holiday. Worcester's Italians were also miffed. They boycotted the parade down Main Street on the grounds that the Irish had stolen a day that properly belonged to them. Meanwhile, the Irish cancelled their St. Patrick's Day festivities. [19] None of this makes any sense if we seek to understand it in terms of "whiteness." A queuing/triangulating paradigm has the immense advantage of permitting us to see, and make sense of, the inter-ethnic dimension of American history. This dimension is singularly missing from the scholarly discussion of whiteness and also of minstrelsy. Use of "passing," the racial analogue to queuing/triangulating brings this dimension into view. Scholarly accounts of minstrelsy, from Lott through Michael Rogin and beyond, have much to say about "audience," but nothing about such grassroots appropriations of the minstrel show as those discussed in "Passing from Light into Dark." [20] If we look at these "performances," we can see that there is an great deal of inter-ethnic stereotyping going on. Swedes performing in the 1924 Norton Company Minstrel Show not only put on blackface, they also put on what we can describe, following the lead of Joel Rosenberg as their "Irishface." [21] In doing so, they were mimicking what the Irish had done earlier, using the conventions of the Minstrel Show to mock other ethnic groups. "Passing" provides another way of widening our investigations and deepening our conversation. All treatemnts of race and racial boundaries had to contend with the possibility that individuals could "pass." In popular culture, this typically meant a black seeking to live as a white. The attempt routinely ends tragically. The racial divide, however porous in reality, is impassible in novels, movies, plays, and short stories. But, as the title of the cartoon that gives "Passing from Light into Dark" its title suggests, one can harmlessly "pass" in the opposite direction. Whites can "black up." Or they can become Oriental or Native American. And, of course, they can safely return. Why would they want to? The standard answer rests upon the dubious proposition that immigrants sought to establish their own "whiteness" by allying themselves to the racial system. This is supplemented by Lott's psychoanalytic speculations about the attractions the black male body held for white men. Hence "love and theft." [22] It is interesting that in formulating the standard answer, scholars have not asked "What did whites do when they "passed from light into dark"? other than to note they sang songs, made outrageous puns, and mocked African Americans while romanticizing the plantation South. They also, as I argue in "Passing," created a cultural space, with an audience of willing co-conspirators, in which the unspeakable could be spoken. Al Jolson's "Gus" could put his hands down a woman's dress; Dinah Crow could criticize the immodesty of women's fashion; Norton Company Swedes could bait the Irish. "Passing" enabled one to cross ethnic as well as racial lines. Swedes could imitate Irish brogues. Jews could mock Yankees. One of the most puzzling aspects of Rogin's examination of "Jews in the Hollywood Melting Pot" is his constant failure to recognize this. In his discussion of "Whoopee!" he described the Eddie Cantor character as "a hypochondriacal Jewish weakling." But, the character, Henry Williams, is explicitly identified as a WASP, and one with inherited money at that. Henry's character suffers with neurasthenia which Rogin, for unexplained reasons, used as a synomyn for hypochondria. He suffers, that is, from chronic fatigue and a generalized series of aches and pains brought on by nervous exhaustion. It is the stereotypical condition of upper-class WASPS, but Rogin writes that "Cantor's stereotypical Jew is a timid neurasthenic." [23] Neurasthenia was not a Jewish stereotype. Blacks could not "pass" in the popular culture. Neither could Orientals. But, Jews could "pass" as WASPs. Eddie Cantor could play Henry Williams. Groucho Marx could play Captain Geoffrey T. Spalding. In missing this, Rogin misses the joke. An example is his treatment of the scene in "Whoopee!" in which Henry, disguised as an Indian, bargains over the price of a rug in Yiddish. "The message is that Jews would have gotten a better price for their land." [24] If the character were "a stereotypical Jew," the scene would be an exercise in self-loathing, evoking one of the oldest anti-Semitic stereotypes. But the character is a WASP. The joke lies in having a Jew, playing a WASP masquerading as an Indian, acting like a Jewish peddler. It lies in the multiple layers of "passing" which, when peeled back, reveal not a Jew, not a WASP, not an Indian, but a scared schnook trying to save his hide. Underneath the layers of ethnic and racial meaning lies, not a stereotype, but the recognition of common humanity. That is why the scene struck both Jews and gentiles alike as hilarious. [25] What led Rogin to identify Cantor in this part as a "stereotypical Jew" are the numerous moments in the film in which Cantor reminds the audience he is a Jew playing a WASP. It is Rogin who points out, ironically in this context, that most movies involving blackface include a scene of the performer putting on the make-up. It is the moment in which he lets the audience in on the secret of his "passing." The many Jewish jokes Cantor and, to cite another major example Rogin discusses, Groucho Marx tell is their way of letting the audience in on the secret of their "passing." This is the moment when performer and audience become complicit in creating a space in which the unspeakable can be spoken. Were Al Jolson, performing on the Broadway stage, to put his hand down a woman's dress, he would have set off a furor of protest. Were an African-American to put his hand down a woman's dress, he would have risked lynching. When Jolson, playing "Gus" in blackface, reached down and grabbed a white woman's bra, it became the comic highlight of "Big Boy," a show that played for months on Broadway and then for three years on national tour and then became a movie. "Passing," so long as it was not from dark to light, created a cultural "free fire zone." Anyone was fair game. Witness the Marx Brothers. Anyone could say anything. Think of Groucho's innumerable vulgar remarks to the ladylike Margaret Dumont. Anyone could do anything. Think of Harpo's practice, in movie after movie, of nonchalantly putting his leg under a woman's arm. But, and this is the point Rogin and others ignore, you could not get away with any of this by being who you actually were. Grouch always played a WASP and one involved, albeit disreputably, in a high status profession. He was a big game hunter, a college president, the president of a country, an opera impressario, a Broadway producer. Chico played Italian con artists. Harpo played characters unrestrained by any cultural upbringing. He played pure "id."

|