https://www.albany.edu/offcourse

http://offcourse.org

ISSN 1556-4975

Published by Ricardo and Isabel Nirenberg since 1998

Poems by J.R. Solonche

EBOOKS

When all the books

at last are ebooks,

will the eNazis come

egoosestepping, will

the eSS come in

their ejackboots

and their cans

of ekerosene to burn

the eJewish ebooks

in their blazing ebonfire?

And what of the eJews?

Will we already

be smelling the esmoke through

the cracks in the ecattlecars?

ON READING AN ESSAY ENTITLED THE POEM AND ITS MEANING IN A FAMOUS POETRY MAGAZINE

When the poem takes its meaning out for its morning walk, there are several ways in which to do so. Some poems use a short leash. Some poems use a long leash. Some poems use a harness in addition to a leash. Some poems use a muzzle as well as both a harness and a leash. Although this technique keeps its meaning pretty well under control, you can still hear it growl at you. This can be very frightening no matter how much the poem may reassure you. After all, you ask, why put the muzzle on the meaning in the first place if it isn't dangerous? Last, some poems use no leash at all. This is the poem that has total confidence and trust in its meaning. Usually the meaning of this type of poem is very friendly. The meaning will want to play with you. It might be overly friendly and slobber on you, so be a good sport. On the other hand, the type of poem that does not leash its meaning might secretly wish its meaning to run away. Chances are you will not encounter this kind of poem on a morning walk with its unwanted meaning. This kind of poem will go about its business in the dead of night.

HAIKU FOR SOLO PIANO

The pianist in black

comes out, shakes hands with the piano.

They are attending the same funeral.

"The Steinway is dead,"

he said. "Wheel out the Yamaha

ha ha ha instead."

"The coffin of music,"

quipped James Joyce.

But listen, listen in living black and white.

The intermission:

Silent piano silent movie.

Unaccompanied.

The pianist in black

comes out, shakes hands with the piano.

They are going to play championship chess.

The huge black mouth,

nearly the size of the summer night.

"Listen," it says. "Here is a dream even longer than yours."

I OFTEN WONDER WHAT IT WILL BE LIKE

I often wonder what it would be like,

the morning I do not wake up.

I wonder if it will be like this winter

morning, for instance, the sun shining

brightly enough but cold and distant,

the lake frozen and silent, a desert of ice,

overhead a v of geese practicing

to stay in shape while another v

follows behind like the other half of

a w hurrying to catch up, my neighbor

in a bathrobe going out to the end of

the driveway to get the Sunday paper.

I hope it is but if not, I will understand.

I hope the news is better but if not,

I will understand.

I WANT TO WRITE ABOUT WHAT I DON'T KNOW

I want to write about what I don't know.

I want to write a sequence of sonnets, for instance,

on the mysteries of the mind, one for each mystery or so.

I want to write about what I don't know.

On botany, macroeconomics, quantum gravity,

I want to compose elaborately complex odes.

I want to write about what I don't know.

The secret language of deaf Babylonians, let's say,

or how nocturnal plants use moonlight to grow.

I want to write about what I don't know.

An epic about my heroic great ancestral father

and how he found my great ancestral mother in the Russian snow.

I want to write about what I'll never know.

What will the world be like in a thousand years?

Will there still be birds called eagle, puffin, jackdaw, flamingo?

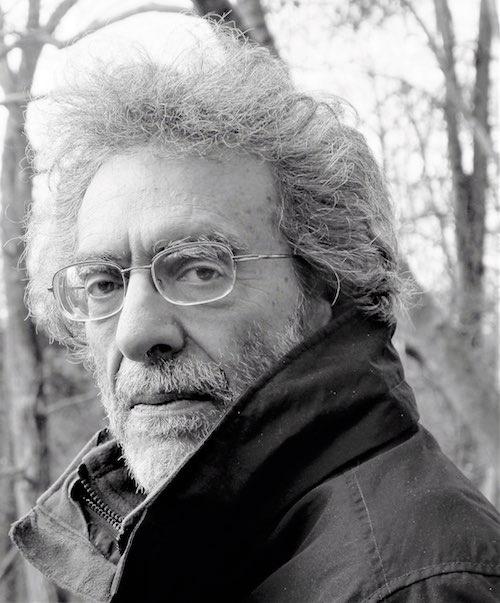

J.R. Solonche is author of Beautiful Day (Deerbrook Editions), Won't Be Long (Deerbrook Editions), Heart's Content (Five Oaks Press), Invisible (Five Oaks Press), The Black Birch (Kelsay Books), I, Emily Dickinson & Other Found Poems (forthcoming from Deerbrook Editions), and coauthor of Peach Girl: Poems for a Chinese Daughter (Grayson Books). His work has appeared frequently in Offcourse.

J.R. Solonche is author of Beautiful Day (Deerbrook Editions), Won't Be Long (Deerbrook Editions), Heart's Content (Five Oaks Press), Invisible (Five Oaks Press), The Black Birch (Kelsay Books), I, Emily Dickinson & Other Found Poems (forthcoming from Deerbrook Editions), and coauthor of Peach Girl: Poems for a Chinese Daughter (Grayson Books). His work has appeared frequently in Offcourse.