https://www.albany.edu/offcourse

http://offcourse.org

ISSN 1556-4975

Published by Ricardo and Isabel Nirenberg since 1998

My Memoir, IV, by Joachim Frank

A Radio Friendship

Axel Staufenberg was the friend I hung out with in my neighborhood during those first years in the Gymnasium (in Germany, the Gymnasium combines middle and high school into one institution), though he went to a different, parallel class with emphasis on the humanities. He was the only son of a doctor who had just moved into our neighborhood. Since Dr. Staufenberg was divorced, my mother spoke in a whispering voice when she referred to him, and from that tone and from the way she rolled her eyes I understood that being divorced was a terrible condition: not only did it reflect on something deeply troubling in the past, but it also cast an ominous light on the present and the future. The present was overshadowed by his single status and the temptation it presumably brought in his daily interactions with his nurse and female patients; the future was burdened by the foreboding of diseases and despair brought on by his present, inevitably promiscuous inclinations. It didn’t help matters that he was tall, black-haired and good-looking. If it had been around at the time he would have done well as a tycoon in the Dynasty series. Eventually, though, my mother had to accept Dr. Staufenberg’s marital status. Not only was his son my best friend, but his practice was also much closer to our house than the practice we used to go to. Much later I saw Dr. Staufenberg go out with a tall blond woman young enough for me to fantasize about – I was in my teens by then. She had a way of greeting me and looking sideways into my eyes that kept me up in bed at night. I saw myself hopelessly inferior to the tall good-looking man.

Axel was black-haired, like his father, but of a pale, waxen, almost puffy complexion. He had a clumsy way of walking, which reminded me of a duck. He asked me to say “Schellfischflosse” – cod fish fin– and when I stumbled over it he told me that people who couldn’t pronounce it properly suffered from a condition called “Gehirnerweichung” – cerebral softening. I mumbled the difficult word often to reassure myself of my well-being.

What brought us together was love of electronics. We took old radios apart and gradually got a glimpse of what made them run. It was just at that time when the first transistors (invented in 1949) were being introduced for widespread commercial use, still much too expensive and incomprehensible to us, so we were stuck with valves for some time. The valves we found in the old radios were of the old kind, almost the size of coffee mugs, shaped as a bowling pin, often with a metal nipple protruding from their heads, providing the connection to a grid inside.

Valves were something we could relate to: electrons streamed off the heated cathode, toward the positively charged anode, but had to make it through the grid which was at a variable potential. Depending on the voltage applied to the grid, fewer or more electrons slipped through. It all made sense in terms of the games we had played in the schoolyard of the elementary school during recess: the members of one team started running off the base and had to make it through a fence formed by the members of the other team to arrive at the goal on the other side.

The word chassis, leaned from French, belonged to our radio tinkering time: it was the name of the sturdy metal box, made of aluminum or sheet iron, that carried the sockets of the valves and formed the body of the radio. Axel had French in class, well before I started with it, and this was one more connection with the art of pulling radios apart and putting them back together. Above the chassis the valves stood upright and orderly like skyscrapers, glowing mysteriously inside as though harboring little munchkins that refused to go asleep. Also mounted on the bright aluminum chassis was the power supply transformer, a solemn, dark, heavy pack of iron sheets with copper windings, standing next to the rectifying valve and the candle-shaped capacitor whose purpose was to smoothen the rectified current. Another big presence above the board was the tunable capacitor – a miracle of design: two interlaced insulated stacks of thin aluminum plates made up the capacity; one was stationary, the other could be rotated, such that the area of overlap could be varied for tuning.

The tunable capacitor along with the copper windings of the solenoid formed the resonant circuit, or Schwingkreis, whose frequency determined the station selected. Mysteriously, like a living thing – much like a socialite in a crowded party – the circuit focused its attention on one signal only, ignoring all others lying left and right from the one picked out on the frequency scale. It was only at the resonance frequency that it could absorb and store energy supplied by the airwaves. Resonance, my father had told me, had to do with a company of soldiers marching across a wooden bridge. He had been in World War I and knew these kinds of things from experience. If they marched at just the right pace, the bridge would bounce up and down with increasing amplitude and finally collapse. If they marched too slow or too fast, nothing would happen. Now that I revisit the world of my parents’ attic after so many years, I find the German word “Schwingkreis” so much more vivid than the bland Latin-based construct “resonance circuit.” Schwingkreis: circle swinging around like a Hula Hoop.

The original radios we built were little more than a tunable oscillating circuit coupled with a rectifier, followed by a couple of amplifiers. They were the squeaking, screechy Bakelite boxes with a large dial wheel in front, which I associated with the messages from the front during the War, the Führer’s barking voice and the low-pitched seductive voice of Lili Marlene. (These were mostly events that took place before my time, but I’d heard recordings when I grew up). It took no time to build one of those boxes, but we sneered at that kind of achievement. We knew the professionals used the superheterodyne principle of reception, or in short, the superhet. It worked on the principle of creating a high frequency signal internally with the exact same frequency as the carrier frequency tuned in. One would obtain the audio signal by mixing the two high-frequency signals, the one created internally with the one pulled out of the air. Since such a receiver essentially contained a transmitter, it was easy to make mistakes resulting in blasting the neighborhood with a surreptitious wandering AM frequency, which created noises like a tunable water flute.

For some time, before Axel’s father built a new practice along with living quarters in the Rosa Achenbach-Strasse, he and his son lived in a brick house in the Austrasse, just separated by the road and the Debus house from ours. (The Au in German is an old word for meadow, it’s part of the name of my birthplace Weidenau, which translates into “meadow with willows,” and Birkenau, which in a macabre way translates into “meadow with birch trees”).

With our intuitive knowledge of electricity, we thought of clever ways to communicate that didn’t involve the telephone. Because, in Germany, one had to pay for every local call by the minute. My parents regarded phone calls as a luxury– my father never understood the purpose of chats, with phone or without – and my mother guarded access to the phone with jealousy and thriftiness: she would burst into the room and asked us to stop. Using the phone was reserved for serious business – finding out if a store was open, cancelling a meeting with friends or relatives, or making a doctor’s appointment.

The first idea Axel and I cooked up was to put two metal rods into the ground at some distance from each other and send the signal after some amplification into the earth. Since we knew the earth was an electrolyte, a wet suspension of soil filled with all sorts of ions, a current would flow between the rods. By drawing lines of equal potential between the rods we reasoned that one could pick up a fraction of the potential difference somewhere else with another pair of electrodes stuck into the earth. But this idea didn’t work at all, as we found out with earphones clipped on: all we heard was a 50-Hertz hum, simply because there are so many other signals around, dwarfing the signal we wanted to get across.

The next idea was to pull a single wire directly across from my house to his, up in the air, using the ground as the other conduit. We worked on this quietly, keeping the idea to ourselves. We pooled our savings and bought 300 meters of a heavy-gauge copper wire. We had to cross several high wires, and managed to do this by flinging a stick to which a rope was fastened over the offending cables. After our wire was in place, we connected our headphones on either end, using one as a mike, the other as a phone, and heard the faintest sounds coming across. Excitedly, I ran downstairs, to call him on the real phone.

“I heard you,” I screamed, “I really did.”

We did get a few messages across, after figuring out what was wrong with our hand-made microphones. The excitement lasted exactly three days. On the third day, when I came back from school, I found a ball of crunched copper wire in the back yard. The wire had been blown down by the wind and come to rest lying across several official telephone cables. The telephone company had dispatched their engineers to deal with the problem. I shook with anger – they had no respect for our possession and had rendered the wire useless. But I also was mad at myself, for the stupid way I had fastened the wire on my side on the attic window frame.

The Birds and the Bees

There were only few things Axel and I did together that didn’t revolve around radios. They were rare but exciting in a different way. Once, we went together to the public swimming pool in the Herrenwiese. I’d gone there a few times without him – each time reluctantly, since I wasn’t able to swim very well, always dragged along by my older sister or brother. The Herrenwiese was a wetland leading from Weidenau to Dreis-Tiefenbach, eastwards. Literally ‘Landowner’s Meadow’, it might have once belonged to a baron of some sort. Large parts were still wild at that time, a large flat meadow criss-crossed with willows and hazelnut bushes, with an abundance of wildflowers and edible plants, such as Sauerampfer – sorrel – and Schlüpfchen – a plant whose leaves had long elastic stems that reached into the ground, and when one pulled a leaf out, the stem would break deep down in the heart of the plant and slip out showing its astonishing pink. For Schlüpfer – slipper – was the name of women’s panties, which were made of nylon and had the slippery elusive quality of that fabric. Both kinds of greens we collected a few times to make salad or soup, but then they were too much associated with War and post-War scarcity to be enjoyable.

In those days industry was encroaching on the Herrenwiese from Weidenau’s side, with an assortment of barracks, lumber yards, and brick buildings of manufacturing plants. On the left, the meadow was bordered by the Schlackenhalde, an enormous mountain of slack left behind by centuries of iron-making. At the border of the industrial field, toward Dreis-Tiefenbach, the old meadows still went on, overgrown with tall weeds and willows. This was the area where, on one of my bicycle trips, I surprised a man and a woman lying next to each other in the brush, but I was at a loss trying to understand what they were doing there in their rhythmic convulsions.

To get to the swimming pool we had to take a 20-minute walk. Once arrived at the Herrenwiese, we took a turn to the right and followed a creek upstream. In summer, the walk along the creek was hot and sultry, with Schnaken – horseflies – descending on us, leaving painful boils on neck, arms and legs. Because of the heat, some kids would jump into the creek, even though the water was not exactly appetizing. One day I saw a girl who might have been 15 stand up in the water, as the top of her bathing suit was slipping down. There I saw budding adolescent breasts, like oversized swollen Schnaken bites, that worried me greatly. Mud trickled down from them, leaves stuck to them. Boys around her watched, gloating. She quickly covered her breasts with her elbows and cowered down in the muddy water.

On that day Axel was in a communicative, silly mood. Once we had arrived in the pool area, and set out to explore the territory, he spotted something he was dying to tell me about. “Go slowly, slowly past the girl with the blue bathing suit,” he giggled. “Do it right now! Take a look between her legs.” I did as he told me, walked over to the other side of the pool, and found four black hairs sticking out at the crotch of her suit, like stray wires from an otherwise perfect chassis. I walked back and joined him in giggling, but I had no idea what about. To that day I had not known that women had hair in that area of the body; the presence of it was freakish, and immediately, having learned this, I thought the fact that she had failed to tug it in showed a degree of negligence and violation of decency that bordered on the criminal.

To an adolescent, Geschlecht, the German words for the sex of a person or for their genitalia, and Geschlechtsverkehr, the sex act – which literally means traffic among genitalia– are troubling words. To begin with, schlecht is the word for bad. A construction starting with “Ge” normally means “all-encompassing”, “total”, as in “Gewitter” where it turns the harmless Wetter – weather– into a thunderstorm. Each kid, early on, finds out that there are two types of people who dress differently, speak with different pitches in their voices, and act differently. Besides breasts, which cannot be easily overlooked, something mysterious is behind those differences – glimpses in the bathroom confirm it: below the hips, between the legs, there is wild territory for the imagination of a child. But in German, unfortunately, the word associated with these differences has the connotation of generic badness. The more my curiosity grew, the more I became convinced that this zone of a woman’s body was forever out of reach. This was almost a hundred years after Courbet’s painting L’Origine du Monde, which caused a scandal in Paris as it revealed a women’s pubic hair, the true exuberance and complexity of that hidden forest.

In giving me one of his final gifts before I left for the gymnasium, Bömbes – a friend in elementary school who’d been hit by a splinter during the war and lost an eye, as outlined in an earlier section of my memoir – , educated me in the subject of the birds and the bees. In German this education is called Aufklärung – the same word as the English “Enlightenment,” as though the state of not knowing where babies came from were akin to the blind, deeply religious state of Medieval Western man. Bömbes, in his eagerness to share his superior knowledge, led me to a corner next to the Kabäuschen – the place under the verandah– out of sight of my parents, stuck the index finger of his right hand into his left cup-shaped hand, and moved it in and out of the symbolic receptacle. As he was doing this, he looked at me smirkingly with his intact eye, while the other stared into the distance like the eye of a sage. I knew what the index finger was supposed to mean, but what the receptacle stood for was beyond my understanding. Once I came to understand part two of his message, I thought no decent girl would even think of such a thing. After that I shuddered at this thought every time I saw a woman on the street and eyed her for signs of a secret blasphemous agenda. But that’s what the word Geschlechtsverkehr stood for– traffic between the all-encompassing badness in all of us. Participating in trafficking of that sort required a decision up-front to give up all moral pretenses, akin to the consignment of one’s body and soul to Satan. With that terrible word, the groundwork was laid for ever-lasting guilt.

The sense of taboo was reinforced by the hysterical behavior of two important women in our house upon being surprised with no clothes on. I once opened the bedroom door, chancing upon my mother in her underwear as she was about to take off her bra. With a scream she ran to the door and shut it against me. Another encounter with my elder sister ended similarly, with a piercing scream, except this time I had enough time to see her bare perfect breasts, just for a fraction of a second, and to get stunned with lasting excitement.

Meyer’s Encyclopedia

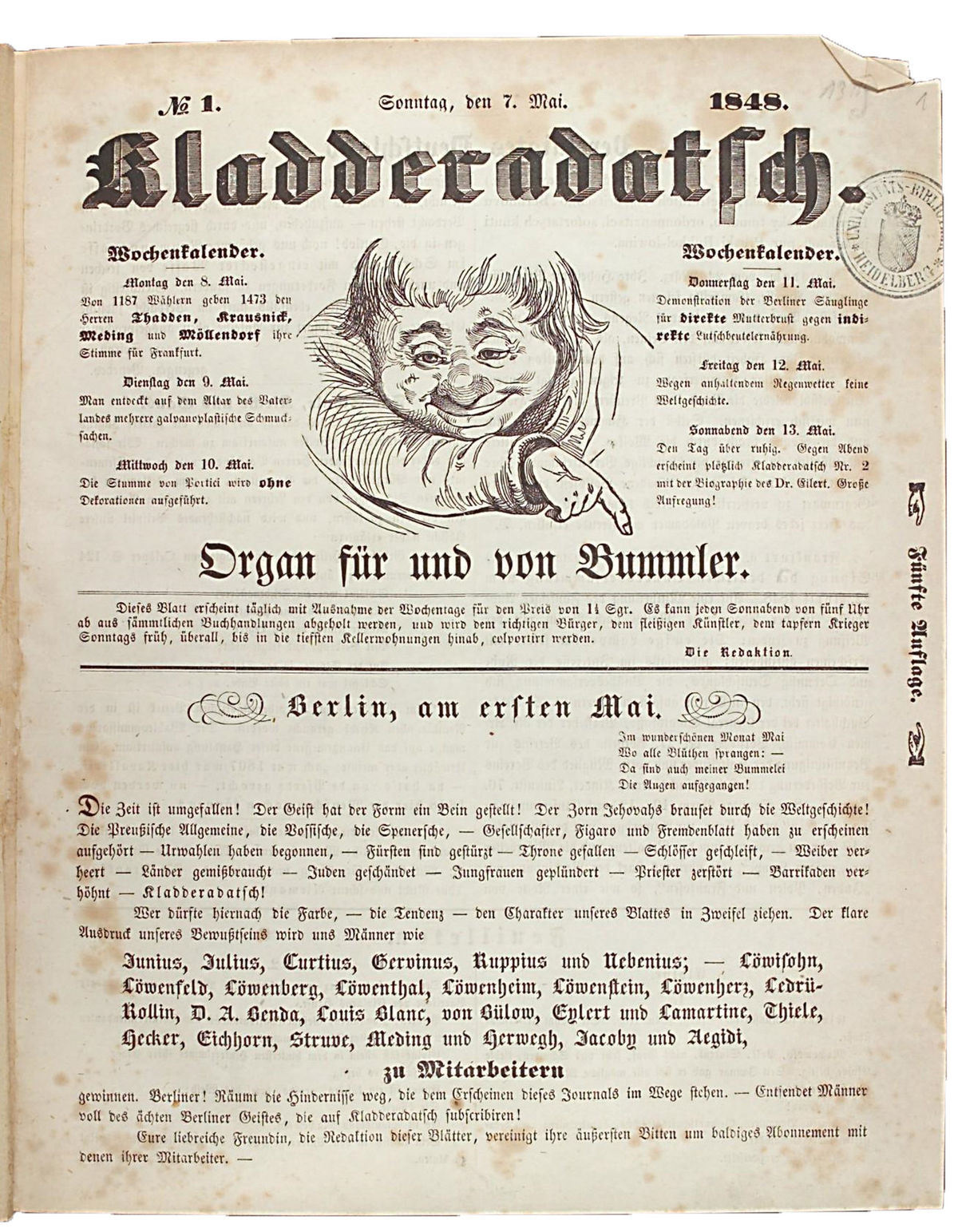

In the sixth to seventh grade, I spent much of my free time studying Meyer’s Konversationslexikon – conversation encyclopedia – whose twenty volumes were enshrined in the middle section of our giant mahogany cupboard, behind glass. It shared a prominent place with Schiller’s Werke – Schiller’s Works –, Fritz Reuter’s Ut mine Stromtid – from my Wander years – and Kladderadatsch– a satirical magazine featuring Bismarck’s political wrangling in Prussia to create the German Reich. Caricatures at that time were always populated by men with enormous heads and tiny bodies. These men were shown in the poses of diplomats at gala events, devouring a piece of cake labeled “Austria” or giving each other portfolios from which some documents had fallen out, scattered on the floor. Bismarck was always shown with a serious, determined face, never smiling. On his bald head there were exactly three short hairs which symbolized three things he stood for, or perhaps the three political entities he was trying to unite. Over the years these hairs had gained a life of their own. By depicting one of them crinkled, the other two standing straight up, the artist could convey a message without spelling anything out in the accompanying legend. One caricature showed Bismarck eating several little people – all politicians labeled with the countries and fiefdoms they represented – who were squirming on his plate. In this black-and-white rendering, the blood being spilled in the process was black. Our anniversary volume of Kladderadatsch next to the volumes of the Lexikon had on its cover the broad whimsical face of the fictitious  commentator under that name, grinning with a broad face and pointing toward the viewer with his finger.

commentator under that name, grinning with a broad face and pointing toward the viewer with his finger.

The idea behind a Konversationslexikon – if one goes by the literal meaning of the name– is to provide you with a gloss of Bildung: what counts is not the substance of knowledge but its appearance, in conversations. Having such a compendium at home meant that one was connected, as if by an umbilical cord, to the universal fountain of all wisdom. Meyer’s Lexikon appeared at the time, at the turn of the century, when all knowledge was thought to be solidified. Human endeavor in science and engineering, over the course of the past two centuries, was celebrated as a towering achievement of mankind, not likely to be surpassed. Engineering had triumphed with the construction of large buildings such as the Eiffel tower and the feats of steam engines, power generators, and railroads. The Industrial Revolution had provided the means to mass-produce food and clothing, insuring virtually unlimited growth. The evolution of species was understood. Whatever else there was to be done in science was merely to finish up some bits and pieces. Merely biology needed some more work.

Meyer’s is a collection of twenty volumes, with approximately 1000 pages a piece, filled with scholarly articles on everything under the sun, even on the universe containing it. Of course, I know now that in the very year that edition was printed, 1906, Albert Einstein published his seminal papers on the photoelectric effect and special relativity that would render many of the articles obsolete. But for me at the time the Lexikon was the Bible. I spent hours reading articles on the unification of Italy, the fauna of the ocean floor, and the design of the telegraph. I believed every word. I believed in the absolute authority of the articles, which dwarfed even that of my father.

The twenty volumes were divided capriciously, with the beginning and ending words imprinted in gold on the spines of the books. The lavish finish went along with the notion of eternal validity. From the time I started to read, the twenty pairs of mysterious words (such as Astilbe bis Bismarck, Mitterwurzer bis Öhmichen) were forever linked like Tweedledee and Tweedledum. To this day I can recount most of them and remember the sense of wonder I had as a child about the meanings and secret subterranean connections between the terms. Again, I was confronted with the strange discontinuity with which this world was ordered: the golden inscriptions on the spines of the Encyclopedia were only the most visible testimony of the chaotic organization of the entire alphabet that put Schicksal, fate, immediately before Schiebeblende, sliding diaphragm and Blut, blood, immediately after Bluse, blouse. It was tempting for me to form associations such as Das Schicksal der Schiebeblende – The fate of the sliding aperture, or Das Blut in der Bluse – The blood in the blouse. The discontinuity of terms that arises when the alphabet is used as an ordering principle was exacerbated by the capricious choice of where to end each volume and where to start the next.

The text was set in a German typeface that was later used ubiquitously in the Third Reich; I suppose because the letters looked as though made up from Germanic runes. The only words set in what we now consider standard letters were Latin terms of classification. Escherichia coli. Things like that. Now that the Enzyclopedia has found its way into my own living room in the Berkshires, decades later, I’m becoming aware that I’m probably one of a few people, for miles around, who is able to decipher this kind of writing.

![]()

The most impressive parts of the Konversationslexikon were the color plates. They were hidden and interspersed in the text like jewels, like the hundred-mark bills my mother used to hide between the sheets in the linen closet. (In her later years she had a hard time finding the bills she had hidden. Later still, there was a period when she would hide the money out of habit, and then forget all about it, until one of the great family events of the year, 50th and 60th birthdays, engagements, weddings, unearthed the bills because the linen was used for guests that came from afar. Eventually, there came the time when the linen stayed put all year round, accumulating treasure, because the time of great family events had passed). The color plates in the Lexikon were meticulously printed from the most exquisite lithographs; there were plates showing the costumes of different peoples; orchids, tropical birds, jellyfish in their natural habitats; and different manifestations of the Northern Light. Each color plate was covered with onion-skin paper, to prevent it from sticking to the prosaic facing page. Often the onion-skin paper was itself covered with drawings and annotations; out of reverence, the editors had avoided disturbing a life-like scene by overprinting symbols and instead put them on the transparent overlay. One had to flip the overlay back and forth to identify a particular medusa or bird.

The most intensive period of my studies coincided with my awakening interest in women. Perhaps more than anywhere else in Germany, sexuality was unacknowledged and mention of it suppressed in our narrow sectarian valley. Sex, as any undeserved pleasure, was associated with sin. The only place where I could find depictions of the female body was in Meyer’s treatments of the antiquity: there were numerous photo-engravings depicting classic sculptures. And the article about “Mensch”, or generic Man, was accompanied by a plate that showed “Die Schöne Wienerin” – the beautiful Viennese woman – as illustration, but with a fig leaf covering the place that I was drawn to most. So I had to choose between complete renderings of the female body that were done in stone and contained the critical junction where three body lines intersect, and, on the other hand, the Wienerin that was closest to breathing life but neutered by censure. Since the sculptures left out every reference to pubic hair – perhaps because of a clash between esthetics and the desire to be realistic, or because there existed an undocumented habit among the old Greeks to keep that area shaven, and the artist stuck to what he saw – and the single photoengraving of an actual nude woman in Vienna was incomplete, I never expected hair in that area and thus was set up for the swimming pool surprise with Axel.

The Schöne Wienerin was far from beautiful, of course. I thought the reason was that her face betrayed the awkward intervention of a fig leaf (question by the adolescent boy: where did they stick the stem of the leaf to keep it up?) in an otherwise quite reasonable portrayal. So I worked myself through the twenty volumes, always with a scratch pad next to the book, writing down volume and page numbers with a note describing the type of picture and ranking the degree to which I was turned on. With this growing data base, I would be able to go straight to the subject, without having to find my way through Hautflügler and Plakatanschriften. In the eyes of my family, studying the Lexicon was an endeavor worthy enough for me to have permission to use my father’s mahogany desk.

That mahogany desk was massive. It fitted into the alcove of the living-room and contained all of my father’s files in locked drawers. On top, his typewriter, an organizer containing pictures and letters, and a lamp. To the left and right of it, on the side walls of the alcove, were little lamps – electric candles, each with a lamp-shade stuck on. Switching off the lamps – snip, snip – was part of my father’s routine every night, along with turning off the radiators, making sure that the back door was locked, and taking his slippers off and letting them fall with a loud clash in a corner of the back hallway. He would switch off the little lights even when I was still sitting at his desk leafing through the Lexikon. (In 1997 I saw the desk newly installed in the house of my sister, in Ahrensburg. It was tiny. It was difficult for me to figure out how it could have accommodated the assortment of objects that are unmistakably in my memory.)

“He’s studying,” my mother would whisper, referring to me, keeping in respectful distance. I was mindful of the possibility of being interrupted, either by my father’s compulsive evening tour or my mother’s sudden bouts of affection, and held the massive volume I was looking at half-open and askew, to be able to close it at an instant’s notice.

As I said, today all twenty volumes of the Lexicon are lined up on a sturdy shelf in my Berkshire house. After both of my parents died, I was successful in arguing my brother out of it, pointing out to him that for him they would just be a backdrop, while for me they would be a living resource. Amazingly, he agreed. In fulfilling my promise, my old self collaborated with the young boy still living inside of me, to produce our own version of Les Mots, published in Eclectica, in 2007.

Author Joachim Frank is a German-born scientist and writer living in New York City and Great Barrington, MA. He took writing classes with William Kennedy, Steven Millhauser, Eugene Garber, and Jayne Ann Philipps. He has published a number of short stories, poems and prose poems in, among other magazines, Eclectica, Offcourse, Hamilton Stone Review, Conium Review, StepAway Magazine , and Wasafiri. Frank is a recipient of the 2017 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. His first novel, "Aan Zee,” appeared in 2019. He just published his second novel, "Ierapetra or His Sister’s Keeper". Frank’s website franxfiction.com runs a blog about everything and carries links to all his literary work.