UAlbany Biologist Awarded $3.3M for Research on Kallmann Syndrome and Olfactory Development

By Erin Frick

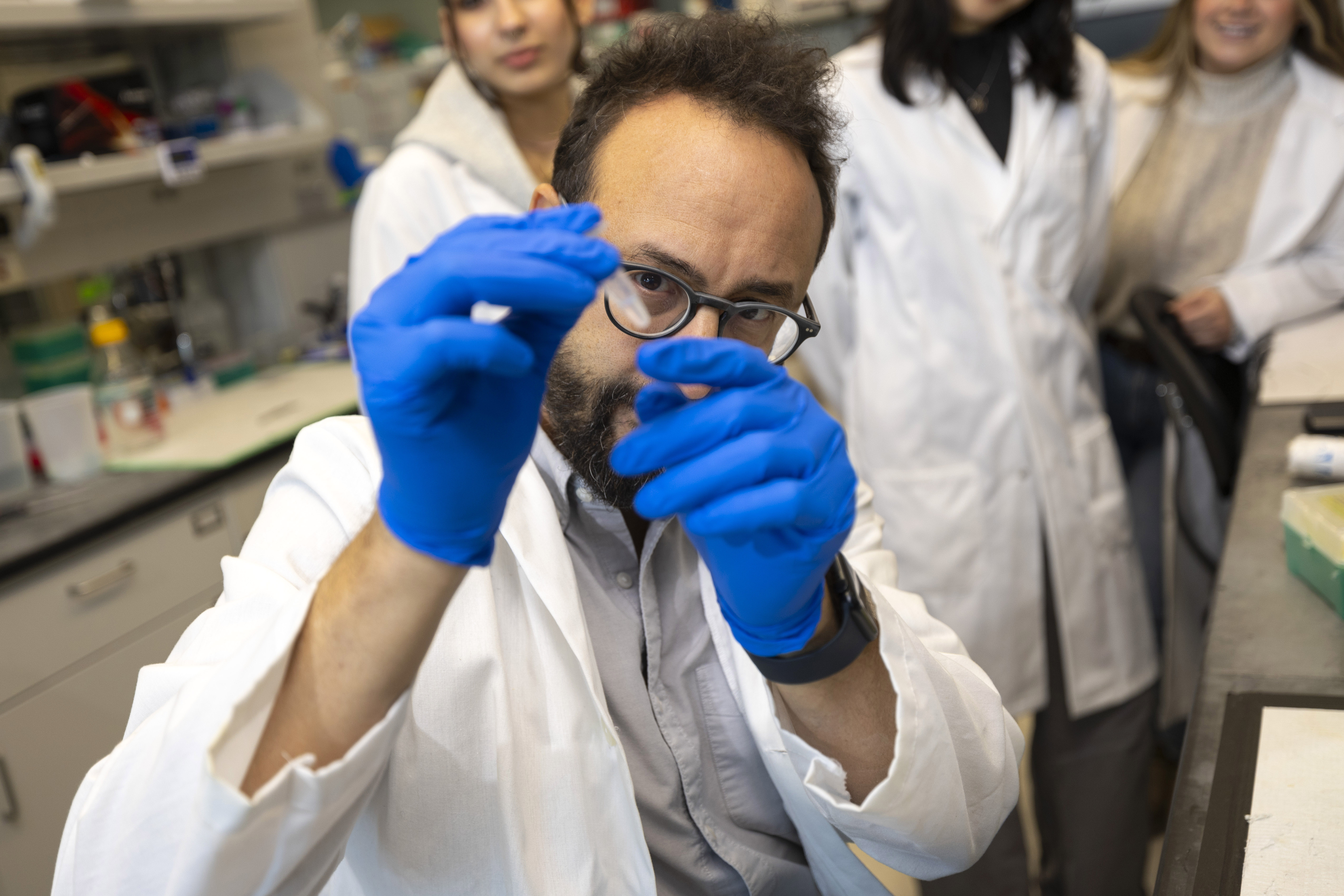

ALBANY, N.Y. (Dec. 5, 2024) — Paolo Forni, associate professor of biology at the College of Arts & Sciences, has received two grants totaling more than $3.3 million from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The funding will support his work studying Kallmann syndrome and related disorders affecting fertility and olfaction.

Olfaction, or the sense of smell, plays a crucial role in reproduction, survival and evolution among vertebrates. Smell helps animals locate food, avoid danger and identify mates.

Individuals with the genetic condition Kallmann syndrome experience delayed or absent puberty (leading to sterility), often accompanied by a diminished or absent sense of smell (anosmia). Understanding the connection between fertility and olfaction has been a topic of scientific investigation for over 80 years.

Forni’s research aims to uncover the causes of Kallmann syndrome and related olfactory disorders to improve diagnostic methods and develop new treatments. The work also holds implications for genetic counseling. Identifying specific genetic mutations associated with Kallmann syndrome and defective formation of the olfactory system could improve the prediction and diagnosis of these and related disorders.

“The olfactory system and the onset of puberty are closely related,” said Forni, who is also affiliated with UAlbany's RNA Institute. “During embryonic development, a group of specialized neurons called gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH-1) migrate from the olfactory placode in the nose to the brain, initiating the hormonal changes that trigger puberty and control fertility in postnatal life. Disruptions in this migration can cause hormonal defects associated with Kallmann syndrome and another form of sterility.

“Previous research in this area has focused on olfactory neurons. Many people with the disorder have small or absent olfactory bulbs, and scientists have long postulated that defective olfactory neuron development caused GnRH-1 migration failures. Instead, our lab has identified a different population of neurons forming a lesser-known structure called the terminal nerve, which arises from the same area in the nose as olfactory neurons. We believe that the defective development of the terminal nerve may be the true origin of Kallmann syndrome.”

Forni’s research suggests that the terminal nerve plays a critical role in guiding GnRH-1 migration from the nose to the brain, a process essential for sex hormone production and maturation. This discovery challenges the long-held view that the olfactory system is essential for fertility, opening new venues of investigation and possibilities for clinical advancements.

“Our recent findings indicate that the terminal nerve is composed of neurons that are genetically distinct from olfactory sensory neurons, raising a chicken-or-egg question: Do we only need an olfactory bulb for GnRH migration, or does the terminal nerve stimulate both the olfactory bulb formation and GnRH migration to the brain? Our research proposes a paradigm shift that could significantly change how researchers study Kallmann syndrome and other disorders associated with anosmia and infertility,” Forni said.

Forni’s group has focused on studying the terminal nerve because one key problem in the idea that the GnRH neurons migrate from the nasal area to the brain along olfactory neurons is the fact that not all mammals form an olfactory system, yet they are still able to achieve fertility.

“Earlier studies have shown that toothed whales, as aquatic mammals, lost their olfactory system during evolution as they do not rely on the sense of smell to find food in water,” Forni said. “Their only nasal structure is located far back on the head and serves for breathing, not smelling. Yet, whales go through puberty, reproduce and also possess a terminal nerve—what is the connection?”

To work this puzzle, Forni's lab uses cutting-edge techniques like single-cell sequencing to track the gene expression profiles of olfactory and terminal nerve neurons during development in mouse models. This work has identified key transcription factors (proteins that regulate gene expression) that are critical for terminal nerve formation. They also investigate how mutations in these genes disrupt important cellular processes, comparing outcomes in mutant and control mice.

A key aspect of Forni’s research involves connecting genetic information obtained in mouse models with human patient data. Collaborating with clinical partners at Massachusetts General Hospital, Forni’s team is searching for patterns that could reveal new genetic causes of Kallmann syndrome and defective olfactory development.

Working with Dr. Ravi Balasubramanian, a reproductive endocrinologist at Mass General, Forni's lab previously identified mutations in a gene called Gli3, which is associated with Kallmann syndrome in both mice and human patients. Their findings indicate that disruptions in Gli3 may impact the formation of the terminal nerve, potentially leading to the disorder.

With support from this new NIH funding, Forni and his group aim to identify additional candidate genes and molecular intersections that may play a role in Kallmann syndrome and related disorders in humans.