PISCES Passes $25M in Funding While Working to Secure Global Trade

ALBANY, N.Y. (Nov. 21, 2024) — Political scientist Bryan Early has been researching strategic trade controls and their role in preventing the spread of weapons of mass destruction since his graduate school days. In 2012, as an assistant professor at UAlbany’s Rockefeller College of Public Affairs & Policy, he founded the Project on International Security, Commerce and Economic Statecraft (PISCES) to focus and continue that work.

Today Early is a full professor and the associate dean for research at Rockefeller College — and remains the director of PISCES, which over the years has received more than $25 million in grants for projects to help global partners develop strategic trade control policies. In October alone, PISCES was awarded seven grants from the U.S. Department of State’s Bureau of International Security and Nonproliferation, totaling more than $6 million.

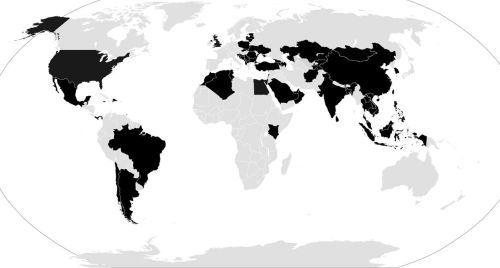

While PISCES was originally founded to help prevent the proliferation of missiles and nuclear, biological and chemical weapons, that work has expanded into protecting a whole range of newer technologies from being misused. Right now, PISCES projects are concentrated in Latin America and the Far East, working with government partners to “regulate trade in dual use commodities that potentially have dangerous security applications,” Early explained.

“To give you some examples: You can use semiconductors in a refrigerator or you can put them in a in a missile,” Early said. “You can use certain chemicals for perfectly legitimate industrial processes, or you could be like Syria, dropping ammonia and chlorine on villages. There’s a lot of aerospace-related products that contribute to building UAVs [unmanned aerial vehicles] — and they could be civilian UAVs or they could be armed UAVs that are dropping bombs.”

Part of the work PISCES does is helping partners develop protocols and trade policies to make sure that the products or raw materials they are selling don’t end up being used for nefarious purposes. And that includes more than bad actors using materials in weapons— it also means protecting technologies from competitors.

“A lot of the recent funding is focused on newer, cutting-edge technologies that maybe have more conventional security applications,” Early said. “You don’t want advanced artificial intelligence used in military weapons, right? And that plays into economic security as well, as you don’t want to lose the next generation of semiconductors and have that technology exploited by competitors.”

And with emerging technologies, Early said, the threat is not always fully identified or understood. “The challenge with these new technologies is that we've identified their potential, and we're confident they're going to be risky. We just don’t know all the risks yet. So it's trying to protect against the next wave of not fully understood security threats associated with these technologies.”

PISCES is a team of eight people, mostly employed by the SUNY Research Foundation, and includes researchers, lawyers, academics and policy experts with experience in technology and government. Members of the team travel a lot and, in addition to helping partners develop strategic trade policies, the work includes demonstrating how trade controls can have economic benefits.

Having effective trade controls and regulations in place can show that countries are safer, more attractive places for investment, Early explained. “It relieves the concerns about whether or not these are safe destinations to export their advanced technologies. And it makes them safer partners for companies that want to include them in their supply chains, because they have greater confidence that the goods and technologies that they host there aren't going to be diverted and misused.”

In addition to its own projects around the world, PISCES — which is housed in the Center for Policy Research at Rockefeller College — partners with the College of Emergency Management, Homeland Security and Cybersecurity and its Center for Advanced Red Teaming.